It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

New Concepts in Managing Achilles Tendinopathy

- Unfortunately, despite its widespread use, the Alfredson protocol has been proven to be only moderately effective at reducing long-term symptoms associated with Achilles tendinopathy.

- Interesting new research out of Australia shows that fluid flow dynamics within the Achilles tendon may play a key role in accelerating recovery.

- Of all the exercises studied, the bent-knee heel drop exercise that specifically targets the soleus muscle produces the greatest increase in interfascicular sliding, while simultaneously placing the least stress on the tendon.

Despite being the largest and strongest tendon in the body, the Achilles tendon is injured with surprising regularity. In any given year, nearly 10% of runners develop Achilles tendinopathy, and the lifetime prevalence of Achilles injuries in middle- and long-distance runners is nearly 50%.1

The high injury rate has everything to do with the extreme forces the Achilles tendon is exposed to while exercising. For example, while recreational jogging places a force of nearly eight times body weight on the tendon, the forces while sprinting and jumping can exceed 12 times body weight.2

Bojsen Moller, et al.,3 point out that even a healthy Achilles tendon can only tolerate a force equal to 14 times body weight, claiming that the Achilles tendon operates within a low “safety zone” in which it is always on the verge of being damaged. This is particularly true for older and previously injured individuals, as tendon strength diminishes with age and trauma.

Achilles tendon injuries are classified by their location: Insertional tendinopathies occur at the Achilles’ anterior attachment point of the calcaneus, and non-insertional injuries typically occur about 5 cm above that point. Because of the terrible blood supply present in the midsection of the Achilles, non-insertional Achilles injuries are more common, as the impaired circulation inhibits cellular remodeling.

The Popular, Inadequate Treatment

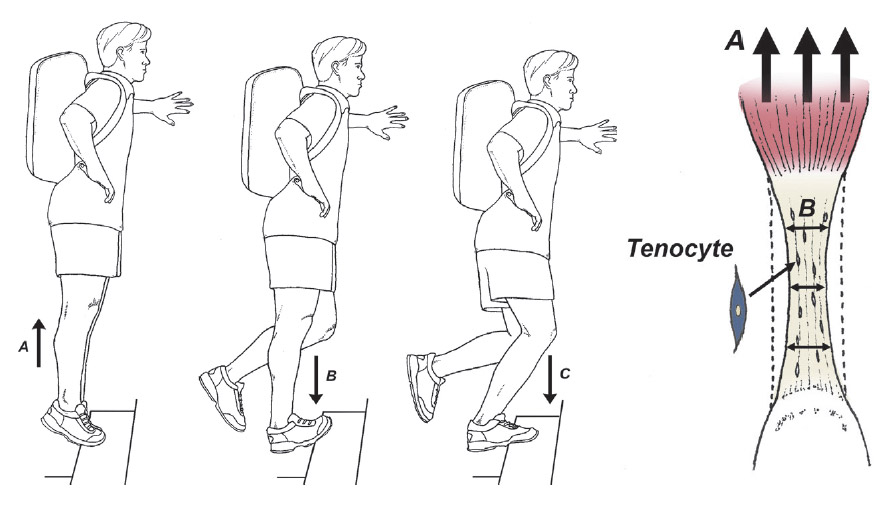

Although there are numerous treatment protocols available for managing damaged Achilles tendons, such as shockwave and/or stem cell injections, the most popular treatment intervention for managing both insertional and non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy is heavy-load eccentric training (Fig. 1).

Unfortunately, despite its widespread use, the Alfredson protocol has been proven to be only moderately effective at reducing long-term symptoms associated with Achilles tendinopathy, as nearly 60% of people treated with this intervention report pain and continued discomfort five years later.4

The long-term results associated with insertional injuries are probably even worse, as this injury is notoriously difficult to treat, even in the short term.

Fluid Flow and Interfascicular Sliding

In an attempt to improve outcomes associated with exercise therapy, researchers have realized that it is important to understand the exact mechanism in which exercise stimulates recovery. To that end, some interesting new research out of Australia shows that fluid flow dynamics within the Achilles tendon may play a key role in accelerating recovery.5

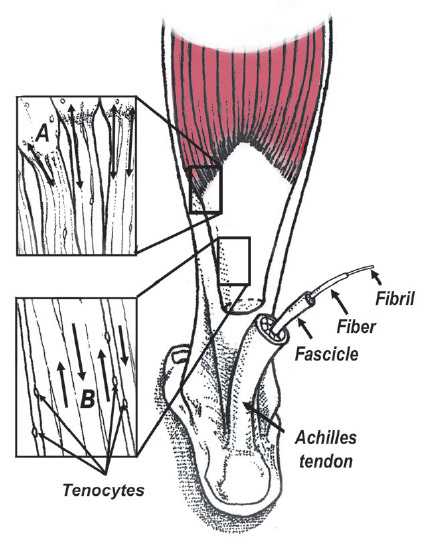

These authors cite numerous studies showing that when a healthy tendon is exercised, there is a significant flow of fluid away from the core of the tendon, and the shear stress from this fluid flow creates a tensile strain that stimulates tenocyte remodeling.6-8 (Fig. 2) This outflow of fluid is absent in tendinopathic tendons.

To identify which exercises most effectively stimulate intratendinous fluid flow, the authors used three-dimensional ultrasonography to monitor flow dynamics as participants performed isometric contractions at intensities that varied from 35-75% full effort, with load durations ranging from two to eight seconds.

Upon completion of the study, the authors determined the subjects performing the heavy-load, long-duration exercises had a 13% reduction in tendon volume, which was far and away greater than any other treatment group. As a result, the authors state that in order to accelerate tendon repair, the applied load must be heavy and sustained for a long duration.

In perhaps the most interesting recent research on the underlying causes of Achilles tendinopathy, researchers from Finland showed that when people with healthy Achilles tendons exercise, different portions of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles pull on their corresponding tendon fibers, creating a nonuniform pattern of interfascicular sliding within the Achilles tendon.9

The nonuniform sliding of one tendon fiber against another mechanically stimulates tenocytes to accelerate tendon remodeling. (Fig. 3) In contrast to healthy tendons, individuals with damaged Achilles tendons show a more uniform pattern with limited variation in interfascicular sliding.

The clinical significance of this paper is huge, as it confirms that in order for the Achilles tendon to be effectively rehabilitated, all fibers of the different calf muscles must participate in force generation, as activity in each muscle gets transferred into the tendon, promoting the nonuniform pattern of fascicle sliding present in healthy tendons.

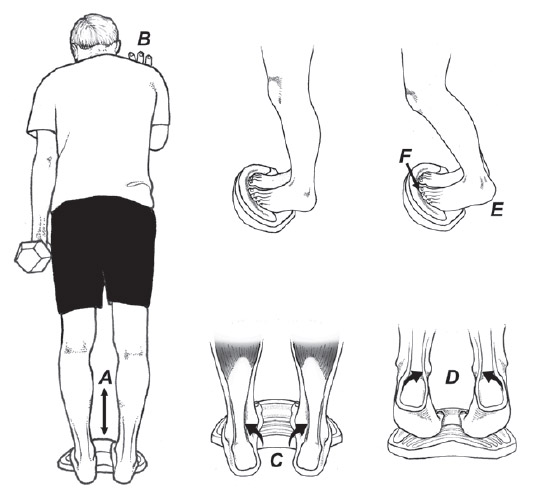

To identify exactly which exercises increase the amount of interfascicular sliding, Handsfield, et al.,10 evaluated tendon fiber sliding patterns as people performed different calf exercises. Of all the exercises studied, the bent-knee heel drop exercise that specifically targets the soleus muscle produced the greatest increase in interfascicular sliding, while simultaneously placing the least stress on the tendon.

The authors claim that this exercise will have “a major role in the future of tendon rehabilitation.” The outcome of this paper is consistent with recent research showing that weakness of the soleus is the single best predictor of non-insertional Achilles injury.11

Because the soleus possesses 50% more muscle mass than the neighboring gastrocnemius muscles, failure of the soleus to generate force would significantly impair interfascicular tendon sliding, which could be corrected with bent-knee heel drop exercises.

My Favorite Recovery Exercise

After looking at the latest research, my favorite exercise intervention for managing both non-insertional and insertional Achilles injuries is illustrated in Fig. 4. The only difference when managing non-insertional versus insertional injuries is that the heel should not drop below horizontal in managing insertional tendinopathies.

I typically recommend four sets of 24 repetitions performed at 30% full effort, as this exercise prescription produces the same increase in muscle volume as heavy-load resistance training,12 which people with Achilles tendinopathy often cannot tolerate. At the end of each set, an isometric contraction is performed to enhance the outflow fluid from the tendon and enhance interfascicular sliding.

I’ve been using this exercise protocol for almost two years now, and in my experience, it definitely produces better outcomes than the Alfredson protocol, especially in elite athletes. Although it requires a fair amount of commitment to perform these exercises daily, some recent research shows that even people who perform their Achilles exercise routine with reduced intensity and for shorter periods of time still get good outcomes.13

Just knowing that it is not necessary to firmly adhere to a regimented exercise routine increases patient compliance, especially in people who dislike doing rehab.

References

- Kujala U, et al. Cumulative incidence of Achilles tendon rupture and tendinopathy in male former elite athletes. Clin J Sport Med, 2005;15:133-5.

- Fukashiro S, Komi PV, Jarvinen M, Miyashita M. In vivo Achilles tendon loading during jumping in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol, 1995;71:453Y8.

- Bojsen-Moller J, Magnusson P. Heterogenous loading of the Achilles tendon in vivo. Exerc Sport Sci Rev, 2015;43:190-197.

- van der Plas A, et al. A 5-year follow-up study of Alfredson’s heel-drop exercise program in chronic midportion Achilles Tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med, 2012:46 :214-218.

- Merza E, et al. The acute effects of higher versus lower load duration and intensity on morphological and mechanical properties of the healthy Achilles tendon: a randomized crossover trial. J Exper Biology, 2022;May 15:225.

- Docking S, et al. Relationship between compressive loading and ECM changes in tendons. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J, 2013;3:7.

- Wall M, et al. Cell signaling in tenocytes: response to load and ligands in health and disease. Metabolic influences on risk for tendon disorders. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2016:79-95.

- Iwanuma S, et al. Longitudinal and transverse deformation of human Achilles tendon induced by isometric plantarflexion at different intensities. J Applied Phys, 2011;110:1615-21.

- Khair R, Stenroth L,et al. Non-uniform displacement within ruptured Achilles tendon during isometric contraction. Scan J Med Sci Sports. 2021;31:1069-77.

- Handsfield G, et al. Achilles subtendon structure and behavior as evidenced from tendon imaging and computational modeling. Front Sports Act Living, 2020;23;2:70.

- O’Neill S, Barry S, Watson P. Plantarflexor strength and endurance deficits associated with mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy: the role of soleus. Phys Ther Sports, 2019 May;37:69-76.

- Burd N, et al. Low-load high-volume resistance exercise timulates muscle protein synthesis more than high-load low-volume resistance exercise in young men. PLoS ONE, 2010; 5(8):e12033.

- Stevens M, Tan C. Effectiveness of the Alfredson protocol compared with a lower repetition-volume protocol for midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2014;44:59-67.

- Wirth S, et al. Flexor hallucis longus hypertrophy secondary to Achilles tendon tendinopathy: an MRI - based case–control study. Europ J of Orthop Surg Trauma, 2021; 31:1387-1393.