New York's highest court of appeals has held that no-fault insurers cannot deny no-fault benefits where they unilaterally determine that a provider has committed misconduct based upon alleged fraudulent conduct. The Court held that this authority belongs solely to state regulators, specifically New York's Board of Regents, which oversees professional licensing and discipline. This follows a similar recent ruling in Florida reported in this publication.

9 Delayed-Onset MVA Injuries (Pt. 3)

Editor’s Note: Parts 1 and 2 of this article ran as web exclusives in the January and February issues, respectively.

7. Spinal Cord Injury Linked to Cervical Stenosis and Spondylosis

Adult patients who enter your practice with cervical stenosis/spondylosis (CSS) are susceptible to a spinal cord injury (SCI) in the event of even a minor MVC. This primarily involves patients over age 40, but may also involve younger adults with congenital narrowing of their spinal canal width.1 Narrowing of the canal due to cervical stenosis or spondylosis combined with a traumatic injury can result in severe injury.1

The bony encroachment associated with CSS further compromises the spinal cord in the CSS patient. Patients with CSS may sustain transient subluxation(s) or distracting injury when involved in a hyperflexion/hyperextension whiplash injury that impacts the spinal cord. Bleeding and inflammation may cause an acute cord contusion and compression in this compromised spinal column patient.1 A posttraumatic syrinx (PTS) may develop several weeks following the date of injury.2

Many of these injuries take several weeks to develop to the point where the clinical picture alerts the physician of this severe injury. A delay in cord edema presentation may extend up to six weeks with no early MRI evidence in 35% of cases.1-2

Patient Symptoms: Initially, the patient may note symptoms typical of a whiplash-associated disorder.3 The SCI patient will present with muscle spasticity, incontinence, bladder spasms, upper extremity weakness and impairment of the lower extremities.1

Clinical Pearls: The patient history will denote an existing diagnosis CSS if known all. Young adult patients may not have been diagnosed with congenital stenosis.

Patients over the age 40 develop cervical spondylosis to some degree in approximately 50% of cases.1

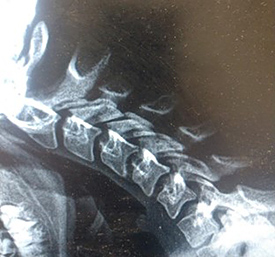

The lateral cervical neutral (LCN) projection can screen for evidence of spinal stenosis.4

Minor MVA trauma can cause SCI in patients with CSS without any early significant MRI evidence of cord edema/compression in 35% of cases.2

A strategy to diagnose latent evidence of SCI/PTS is to order an initial C-spine MRI when the clinician is first aware of the CSS condition. Then, repeat the MRI at three and six weeks even when pronounced SCI symptoms are absent to rule out a developing injury.2

References

- Ronzi Y, et al. Spinal cord injury associated with cervical spinal canal stenosis: outcomes and prognostic factors. Ann Phys Rehab Med, 2018

- Rumboldt Z. Clinical Imaging of Spinal Trauma, A Case Based Approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018: p. 105.

- Rumboldt Z, Op Cit, p. 31.

- Yoo DS, et al. Spinal cord injury in cervical spinal stenosis by minor trauma. World Neurosurg, 2010 Jan;73(1):50-2; discussion e4.

8. Alar Sprain (and the BAR Sign)

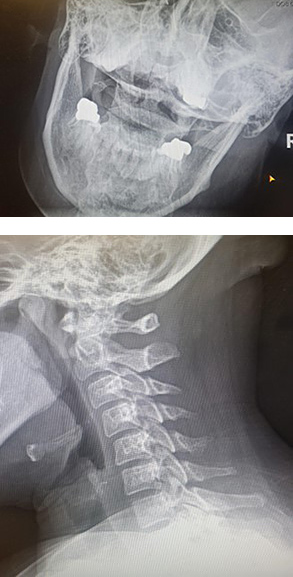

Injury to the alar ligament is normally identified by plain film and/or videofluoroscopy evaluation of the anterior-posterior open mouth (APOM) compared to right and left APOM projections. The hospital ED may also note the injury on CT/MRI. These injuries are more likely to occur when the patient's head was rotated and in flexion at the time of impact.1-2

An “overhang sign” as noted of the right alar mass below is suggestive of an alar ligament injury. Also noted is a larger right lateral mass width. An increased lateral dens atlas space (LDAS) with deviation of the odontoid process is indicative of an isolated unilateral alar ligamentous subfailure (IUALI).3-6

See the three findings in the photo below.

Below is a normal flexion view of an uninjured patient with no MVA history.

The next photo below is a picture of a dynamic/follow-up XR taken in the third week post injury. Note the anterior subluxations, Meyerding grade 1 (1-3 mm) at C2, C3, C4, C5 and C6.7 An MRI demonstrated a C4-5 acute traumatic disc herniation.

The photo below demonstrates a dynamic/follow-up XR taken in the third week post injury. Notice the very straight “BAR”-like appearance of the cervical spine. The “BAR” sign represents latent evidence of an alar sprain on the lateral cervical spine flexion view of a dynamic XR in the third to fourth week of recovery.

An MRI was ordered due to persisting left hand paresthesias and suboccipital headache. The MRI returned with findings of C5-6 and C6-7 disc bulge, but also with edema at the clivus. There were no observed radiographic findings of an alar sprain injury on the initial radiographs. The views included APOM with right and left APOM lateral bending taken due to the patient history of neck flexion with head rotation at the time of impact.

The next XR is of a patient who consulted my office for treatment of persisting neck pain, headache, vertigo and right arm paresthesias. She was in an MVA six months prior.

Imaging demonstrated the three signs of an alar sprain injury on the right lateral bending APOM. The “BAR” sign is represented on the lateral cervical flexion XR.

The patient provided me with a post-accident MRI report from the MVA on her next visit. The imaging report not only demonstrated multilevel disc herniation, but also clivus edema denoting IUALI.

Note the very atypical straight “BAR”-like appearance of the cervical lateral flexion view now six months post injury. The finding coincides with the history of an alar ligament injury.

In the performance of follow-up/dynamic XR in over 1,500 MVA cases, this finding was only demonstrated in two tests, but was 100% accurate in identifying IALI even when no APOM findings were observed on the initial radiographic examination.

Patient Symptoms: The symptoms associated with acute and even six month post-IULAI are similar and may be indistinguishable from whiplash-associated disorder (WAD) symptoms. The IULAI symptoms may include headache, vertigo, neck pain, upper back pain, arm pain, neck tenderness, range-of-motion limitation particularly in rotation, insomnia, visual disturbances, brain fog, jaw symptoms, dysphagia and fatigue.8-10

Clinical Pearls: Patient history indicators noting head rotation with cervical spine in flexion at the time of impact should warrant special clinical concern for IULAI.

Symptoms of IULAI may mimic or be consistent with cervical sprain strain injury.

The vertical lift component of the cervical distraction test in the third week post injury that now produces sharp pain at the suboccipital region has indicated IULAI on MRI follow-up.

Plain film imaging to include APOM with APOM lateral bending projections is suggested with a cervical flexion with head rotation MVA history.

The “BAR” finding when follow-up/dynamic XR is performed is indicative of IULAI.

MRI to confirm or deny IULAI presence is recommended when signs or symptoms of IULAI are present.

Most IUALI recover with conservative treatment however surgical intervention is ultimately required for the most severe cases.3,8-10

References

- Reich C, Dvorak J. The functional evaluation of craniocervical ligaments in side flexion using x-rays. J Manual Med, 1986;2:108-113.

- Freeman M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of videofluoroscopy for symptomatic cervical spine injury following whiplash trauma. Int J Environ Res Pub Health, 2020;17:1693.

- Reeves BC, et al. Isolated unilateral alar ligamentous injury: illustrative cases. J Neurosurg Case Lessons, 2024 Apr 1;7(14):CASE23664.

- Foreman S, Croft C. Whiplash Injuries: The Cervical Acceleration/Deceleration Syndrome; 2nd Edition, Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002: p. 26.

- Reich C, Dvorak J. The functional evaluation of craniocervical ligaments in side flexion using x-rays. J Manual Med, 1986;2:108-113.

- Pedley J. Cervical Spine: Case Presentations.

- Munakomi S, Das JM. Cervical Subluxation. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

- Foreman S, Croft C. Whiplash Injuries: The Cervical Acceleration/Deceleration Syndrome, 3rd Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002: p. 61.

- Evans R. Neurology and Trauma. Oxford University Press, Inc., 2006: p.p. 426-434.

- Foreman S, Croft C, Op Cit, p.p.131-132.

9. Delayed Instability

Motor-vehicle collisions can cause a variety of patient injuries. While the majority of injuries discussed above can be diagnosed within the first 3-4 weeks following the MVC, delayed instability may take several weeks to even months to fully develop. Delayed instability occurs in 5-20% of MVC cases, primarily in the cervical spine, but can also occur in the lumbar spine. At the higher end of the statistic, this represents a significant percentage of MVC cases.1-2

Delayed instability (DI) is a discoligamentous injury. At the onset of a MVC, the patient may suddenly and without warning undergo rapid acceleration and deceleration as a result of the collision forces. If the sudden forces acting on the spine cause elongation of the ligamentous structures beyond their tensile length, sprain occurs. White and Panjabi describe this as traumatic vertebral displacement into the plastic range that is beyond the normal elastic range of ligamentous recovery. The result is a vertebra on plain film XR that now exhibits post-traumatic residual deformation.1,3

The injured ligaments may then develop “creep” resulting from normal day to day actions or contraindicated treatment when the injured vertebral level that was deformed into the plastic range but was not earlier identified.3-4The posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) may be injured as a result of the acceleration and deceleration forces as indicated by an anterior subluxation. This injury is visualized on the lateral cervical neutral and/or a cervical flexion projection. Croft, White, Panjabi and others note that an anterolisthesis of 3.5 mm or greater is regarded as clinical instability.2,4-5

Patient Symptoms: The symptoms associated with DI will be similar to the original spinal injury symptoms noted from the MVC. There are no specific symptoms associated with DI; however, the original symptoms just never seem to resolve or may even be worsening.6-7

Sclerotome-derived referred pain generated from injured deep skeletal and soft-tissue structures is the likely cause of continuing DI pain. The pain may be deep and achy in quality, and may be noted at the location of the cervical or lumbar instability Sclerotome pain patterns may extend to the upper back or even involve the upper extremity with a cervical injury. Lumbar DI sclerotome symptoms refer to the flank, buttock, gluteal, groin, anterior and posterior thigh, but not below the knee.6-7

Clinical Pearls: Delayed instability is a major cause of post-traumatic chronic neck and low back pain, impairment and disability.1 Anterior subluxation is the most predictive finding of future DI.1,7 Initial ED evaluation following EMS transport may fail to identify anterior subluxation due to protective spasm. When no concerning criteria are presented, plain film or CT examination may not have been performed due to NEXUS protocols.1 MRI examination following the inflammatory stage of repairs may fail to identify PLL sprain.1

Anterior subluxation may not be readily available until the patient can actively flex the cervical spine a minimum of 30 degrees following the date of injury. This may not be possible at the initial office visit due to spasm from injured myofascial tissues and/ or deeper structure injuries early in the acute stage of healing.9-10

Dynamic x-ray is the gold standard to rule in/out the probability of DI.1 An incomplete evaluation or misinterpretation of the study failing to note anterior subluxation are frequent causes of a missed DI diagnosis.1

References

- Yeo C, et al. Delayed or missed diagnosis of cervical instability after traumatic injury: usefulness of dynamic flexion and extension radiographs. Korean J Spine, 2015;12(3):146-149.

- Foreman S, Croft C. Whiplash Injuries: The Cervical Acceleration/Deceleration Syndrome; 2nd Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002: p. 53.

- White A, Panjab, M. Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1978: p. 214.

- White A. Panjabi M, Op Cit, p. 224.

- Solomonow M. Ligaments: a source of musculoskeletal disorders. J Bodyw Move Ther, 2009;13(2):136-54.

- Foreman S, Croft C. Whiplash Injuries: The Cervical Acceleration/Deceleration Syndrome, 3rd Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002: p. 378.

- Foreman S, Croft C, Op Cit, p.p.393-405.

- Hoffman JR, et al. Selective cervical spine radiography in blunt trauma: methodology of the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS). Ann Emerg Med, 1988 Oct, 32(14):461-9.

- Como J, et al. Cervical spine injuries following trauma. J Trauma, Sept 2009;67(3):651-9.

- Freiheit T. “Diagnose Sprain Injuries in MVA Cases with Dynamic X-Rays.” Dynamic Chiropractic, November 2015. Read Here

Final Thoughts

Many MVA injuries, including those described above, present with very similar symptoms. Due to the possibility/probability of these injuries, it is important to examine any patient involved in an MVA just after the accident; and perform a progress examination two and four weeks following the initial evaluation throughout the first month to ensure that no injury goes undiagnosed. Provide treatment as indicated.

Author’s Note: Necessary patient photo consent was obtained.