New York's highest court of appeals has held that no-fault insurers cannot deny no-fault benefits where they unilaterally determine that a provider has committed misconduct based upon alleged fraudulent conduct. The Court held that this authority belongs solely to state regulators, specifically New York's Board of Regents, which oversees professional licensing and discipline. This follows a similar recent ruling in Florida reported in this publication.

Are Disc Degenerations and Herniations Just Incidentalomas?

A new patient brings in an MRI showing moderate-to-severe disc degeneration to several lumbar discs. This patient has no pain, but is mildly restricted in all ranges of motion, and failed her lumbar spinal muscular endurance physical performance tests. She asks you if disc degeneration is normal for a 39-year-old.

How Do You Answer the Patient's Question? What Does the Current Research Say?

We examine a valid and relevant systematic review that calculates the prevalence, by age, of disc degeneration of the lumbar spine on imaging in individuals without pain or dysfunction. This study was published in the American Journal of Neuroradiology.1 The research team consisted of 13 medical researchers, all from prestigious organizations: the Mayo Clinic, the University of Washington, Oregon Health and Science University, Henry Ford Hospital, and the University of California. The review was funded by National Institutes of Health.

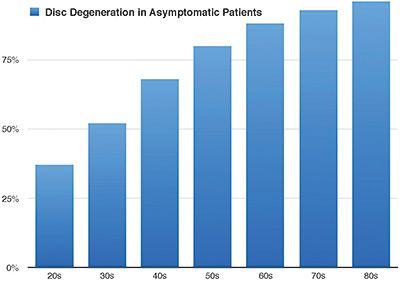

The researchers examined the prevalence of degenerative changes across patient ages by decade (20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s). They found 33 articles reporting imaging findings for more than 3,000 individuals without pain or dysfunction.

The "Disc Degeneration in Asymptomatic Patients" graph demonstrates the conclusions of this study: Imaging findings of degenerative changes such as disc degeneration can be part of the normal aging process, rather than pathologic processes requiring intervention.

Previous studies support these conclusions. Degenerative findings are not necessarily associated with the degree or the presence of low back pain. Steffens, et al., performed a systematic review and found no consistent association between low back pain and MRI findings of Modic changes, disc degeneration and disc herniation.2

In a large case-control study, vertebral endplate changes were not associated with chronic low back pain.3 Two systematic reviews examined the prognostic role of MRI findings on patient outcomes. Both failed to find a relevant prognostic association between imaging findings and clinical outcomes.4-5

Degenerative changes are a biological reality, but pain and disability are not the foregone sequelae. Many imaging findings that traditionally were presumed to be pathologic are common in asymptomatic populations.

Overall, the current research suggests degenerative changes in the spine are frequently not the source of pain. It appears that spinal degenerative changes do not establish a de facto treatment target.

Do Disc Herniations Require Surgery?

A new patient brings in an MRI showing a sequestrated disc in the lumbar spine. About a month ago, this patient lifted a heavy box in an awkward manner and felt immediate back and leg pain. Subsequently, an orthopedic surgeon recommended surgery.

Because of scheduling issues, the patient postponed the surgery. She asks if you can help her disc herniation and back and leg pain. What is your response? What does the current research demonstrate?

Let's examine a pertinent systematic review to determine the probability of disc regression after nonsurgical treatment of lumbar herniated disc. This study was published in Clinical Rehabilitation.6 The research team consisted of six international medical researchers.

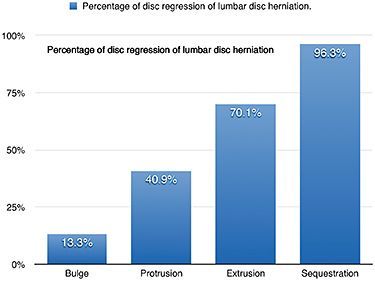

The research team examined studies of patients with lumbar disc herniation who were treated nonsurgically with manual therapy, bed rest, analgesics, NSAIDs, exercise, traction, or steroid injection. Nine studies were included, representing 540 patients.

The "Percentage of Disc Regression of Lumbar Disc Herniation" graph demonstrates the conclusions of this study. The higher the grade of disc herniation type, the higher the rate of regression. In other words, the worse it is, the better the results! Lumbar disc herniation can regress or disappear without surgical intervention.

Clinical Pearls: For You, Your Patients and Insurance Companies

Disc absorption by macrophage phagocytosis and enzymatic degradation is the likely mechanism of regression for disc herniation. This absorption process can reasonably explain the complete disappearance of the herniated disc. Because sequestration and extrusion disc herniations have greater migration exposure into the epidural space, they have a surrounding inflammation. It is not surprising that these types of herniations have the highest rate of complete resolution compared with protrusions or bulges.

Researchers have found that patient symptoms can improve even without disc herniation regression. So, it is more important to treat the patient, not the photo.

The natural history of lumbar disc pain is favorable, and 70 percent of patients recover from sciatica without surgery within six weeks.7 In an observational study of surgical and nonsurgical treatments, no significant difference was demonstrated after four years.8

Perhaps insurance companies should update their reimbursement protocols. Based on science, they should exclude spinal surgery for disc degenerations and herniations, and instead encourage a conservative package of chiropractic care.

Author's Note: The research presented in this article is also available in video format by clicking here or going to the Video Archives here.

References

- Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, et al. Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. Am J Neuroradiol, 2015;36:811-6.

- Steffens D, Hancock MJ, Maher CG, et al. Does magnetic resonance imaging predict future low back pain? A systematic review. Eur J Pain, 2014;18:755-65.

- Kovacs FM, Arana E, Royuela A, et al. Vertebral endplate changes are not associated with chronic low back pain among Southern European subjects: a case control study. Am J Neuroradiol, 2012;33:1519-24.

- Modic MT, Obuchowski NA, Ross JS, et al. Acute low back pain and radiculopathy: MR imaging findings and their prognostic role and effect on outcome. Radiol, 2005;237:597-604.

- Chou R, Fu R, Carrino JA, et al. Imaging strategies for low-back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet, 2009;373:463-72.

- Chiu CC, Chuang TY, Chang KH, et al. The probability of spontaneous regression of lumbar herniated disc: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil, 2015;29:184-95.

- Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med, 2001;344:363-370.

- Weber H. Lumbar disc herniation. A controlled, prospective study with ten years of observation. Spine, 1983;8:131-140.