It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

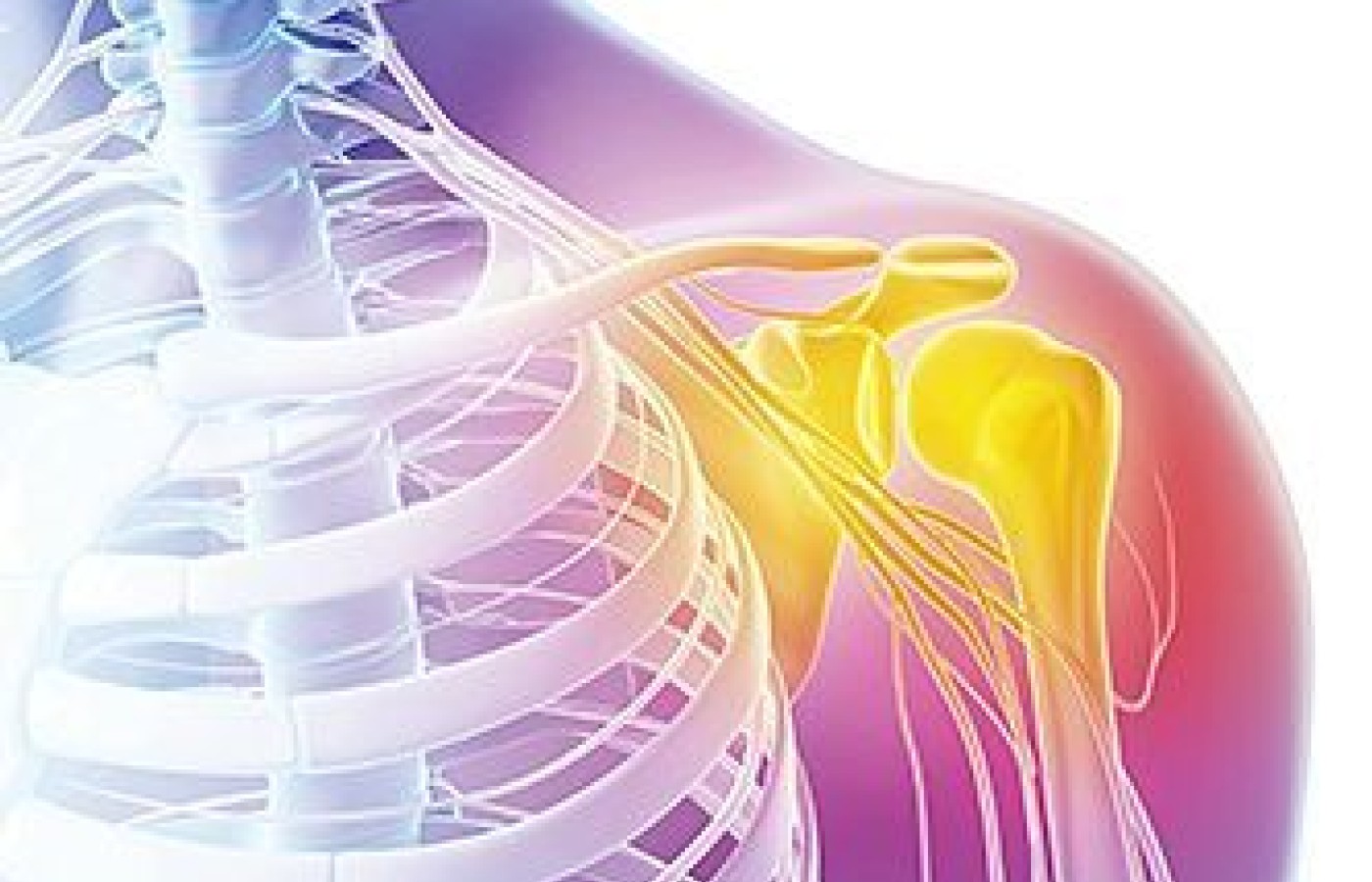

Taking the Freeze Out of Adhesive Capsulitis

Adhesive capsulitis or "frozen shoulder" is a relatively common condition resulting in severe shoulder pain and global loss of glenohumeral joint range of motion. Incidence of the condition is approximately 3 percent in the general population. Risk greatly increases for patients diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Adhesive capsulitis often occurs with an insidious onset and can be idiopathic in nature. Whatever the cause, figuring out a treatment strategy often poses a challenge to manual medicine practitioners.

Classically, the natural history of adhesive capsulitis has been described in three sequential phases: a painful stage, a freezing stage and a thawing stage. However, validating evidence of this classification is lacking. Pain and limited range of motion may occur in all phases of this complex condition, which doesn't follow a stepwise course.

Adhesive capsulitis is considered to be self-limiting. However, pain and limited range of motion may persist for one to two years and 10 percent of patients never regain full range of motion.

Treatment Challenges

Treatment strategies often focus on decreasing pain and restoring range of motion. Unfortunately, there is insufficient high-level evidence to either support or refute many of the commonly employed conservative therapies, including ROM exercises, stretching, joint mobilization, and a multitude of other PT modalities aimed at decreasing pain and inflammation. Often the "phase" in which the patient is considered to be will dictate which treatment technique is used.

Although manipulation / mobilization is the mainstay therapy applied by most chiropractic physicians, most would agree that aggressive mobilization is contraindicated during the painful stage, as exacerbation of pain may occur, reducing compliance to the prescribed treatment plan. Typically, more aggressive techniques are exercised during the subacute and chronic phases, during which pain is typically less of an issue for patients.

Although glenohumeral and scapulothoracic joint manipulation continues to be the choice of manual therapy for this condition, therapeutic benefit can be minimal. At least one case study examined the use of traditional therapies in addition to thoracic spine manipulation. Traditional therapies included ROM exercises, passive stretching, and scapular / glenohumeral mobilization. With the inclusion of thoracic spine manipulation, increases in shoulder ROM were remarkable and the patient's pain decreased markedly.

Although the underlying mechanisms for this drastic improvement following spinal manipulation and manual therapy are not well-understood, it emphasizes the interconnectedness of the human body. Whether the improvement was neurophysiological, biomechanical or a combination of the two, the end result was increased ROM and reduced pain – the two primary goals of treatment.

Adjustment Techniques

Glenohumeral Joint Posterior Glide @ 90° of Shoulder Flexion

Palpation

- The patient is supine with the hand of their targeted shoulder behind their head.

- Position yourself in a fencer stance with your outside hand under patient's scapula to stabilize it and your hip bracing their arm.

- Your inside hand contacts the patient's olecranon, adducts their shoulder slightly and glides the shoulder posteriorly.

Manipulation

- Set the drop piece.

- Move the hand that was under the scapula to the brachium.

- Thrust lightly anterior-posterior into the drop piece 3-4 times.

Scapulothoracic Articulation: Prone Scapular Distraction

- With the patient prone, sit beside their affected shoulder.

- Place the patient's hand beneath their ASIS; place your cephalad supinated forearm on your knee and place that hand beneath the patient's anterior shoulder.

- Use your cephalad knee to lift the patient's shoulder posteriorly as your caudal hand's fingers try to reach beneath patient's scapula and lift it away from the thorax.

- Hold position for 10-12 seconds.

- Repeat 3-4 times.

Cross Bilateral Transverse Pisiform With Torque for T4-T10

- Patient position: prone on the table

- Doctor position: Begin in fencer stance, facing patient's feet, place contact. Next, pivot to face patient's head and place second contact. Finally, pivot to again face patient's feet for the thrust.

- Tissue pull: Torque will be created by the changes in doctor position. With first contact, tissue pull laterally. With second contact,tissue pull toward the head.

- Contact: While facing the patient's feet, use hand closest to them, and contact the contralateral TP with the pisiform. Next, while maintaining that contact, face the patient's head. Take a contact on the ipsilateral transverse process, tissue pull headward, fingers pointing headward. Then face the patient's feet again.

- Thrust: Bring your own body weight over the contact. The thrust is a drop, completed by quickly bending the knees.

Hypothenar Spinous CT

- Procedure: This adjustment addresses lateral flexion / rotation, "sided" restrictions. It is a variation of the bench TM, especially helpful for doctors whose thumbs overextend.

- Patient position: prone.

- Doctor position: Fencer stance with head cephalad of the patient's head. Once contact is made, come close enough to hypothetically whisper in the patient's ear.

- Contact: Doctor contacts ¾ inch (toward your body) from the SP; a soft, hypothenar contact with enough arch in the hand to allow one finger to slip under.

- Tissue pull: toward the midline.

- Indifferent hand: Ask the patient to turn their head away from you. Traction cephalad by contacting in area of occiput / mastoid.

- Adjustment: This is a quick thrust, not a loaded adjustment. After contact is made and traction is in place, thrust straight across.

Resources

- Ewald A. Adhesive Capsulitis: A Review. Amer Fam Phys, 2011 Feb 15;83(4):417-22.

- McCormack J. Use of spine manipulation in treatment of adhesive capsulitis: a case report. J Manip Ther, 2012 Feb;(1):28-34.

Editor's note: This is the fourth article in a series on chiropractic techniques to treat challenging patient presentations. "The Struggle to Heal the Cervical Syndrome" kicked off the series in the June 1, 2014 issue.