It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

Where Were You When the World Stopped Turning?

More than 100 doctors of chiropractic participated in relief efforts following the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks that left 2,753 dead – including 343 firefighters, 60 police officers and eight paramedics / emergency medical technicians – and far more than the New York City skyline forever altered. Dr. Richard Gorgo Jr. was one of those DCs who selflessly donated his time, skill and compassion during that surreal, yet all-too-real moment in history. This is his remarkable story. Where were you when the world stopped turning? For Dr. Gorgo, who volunteered for more than three months following that infamous day, the answer is Ground Zero.

Where were you when the world stopped turning? The famous Alan Jackson song with that very title, composed only days after the terrorist attacks that brought down the Twin Towers, still creates an emptiness in the pit of my stomach and hollows my spirit. The chilling lyrics remind me so much of those days. Hard to believe it's been 10 years; 10 tumultuous years. None of our lives has been the same since that day. It seems as if everyone has a story about it. This is mine, as myopic as it may seem.

While I sit here attempting to type, my hands are already cramping, a lasting symptom of an illness that plagues so many of us who worked at the World Trade Center site. (I should talk about it a little in case there are any volunteers who read this who have not been diagnosed properly or treated, but my battle with this illness is a subject for another day.)

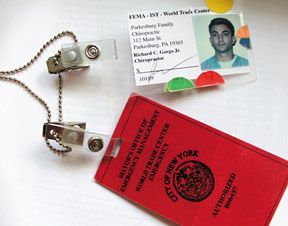

As I mull through a box full of memories hidden for a decade in my basement, I see NYPD, FDNY, and Urban Search and Rescue badges and hats. (A common practice for fire departments and other service teams around the country is to exchange shirts or patches. It's a way of saying "thank you" and accepting you into their family.) I pick up a children's book called September 12th given to me by a schoolteacher, letters from children, letters from friends, signed T-shirts, hardhats and more. I'm completely overwhelmed. How do I express all these memories? How do I put all of this to paper? Every object I touch means something, has a story and brings back memories.

What part of all this do I keep private? What part of it needs to be heard? How much is needed to tell the story? I don't know. I can tell you that it hurts to dig through this stuff; that the emotions are suppressed, just under the surface; that they are never gone. I can't imagine how our veterans must feel, because I have seen nothing like they have and yet I'm trembling as I touch this stuff. I pick up my hardhat, unused since 2001; it still fits pretty well, as do the different respirators we were given to wear (at least we were supposed to wear them).

This story isn't just about me, though, although it's my story. The reason I want to tell it is because of the kind, generous and compassionate people who became part of my life and whose lives I became a part of. This story is about chiropractic; it is about how important a role we played in helping begin the healing of our nation.

Who am I, you may ask? Officially, I'm nobody. I woke up as you did in on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, gathered up my paperwork and headed off to my accountant's office. I checked in with his secretary and asked her what movie was playing on the television. She told me it was no movie, and at that moment the second plane hit. It's the first time I've felt the kind of fear that comes when you realize things happen completely beyond your control.

I immediately called my mother to see if she'd heard from my sister, who lived in New York City at the time. I tried to contact my sister and other family members in New York City. Then I knew I had to do something. I left my accountant's office and began the approximately three-hour trip to New York City (I practiced in Parkesburg, Pa., back then), calling some friends along the way. But I was turned away at the Holland Tunnel and returned home disheartened.

The next day, one of my staff members invited me to church. "They're going to pray for America," she said. While we were praying for the country, the congregation also prayed that I would be able to make it safely and effectively into New York City. That night, I packed up all the medical supplies I could find, including my chiropractic table and all the towels, bed clothing and pillows I could get my hands on. My best friend from New Jersey offered to drive up with me.

We drove 2 1/2 hours and wound up again at the entrance to the Holland Tunnel. This time, instead of turning around, I pulled my window to the side of the police officer on duty. (You have to know how dangerous this is at a time when no one knows who the enemy is.) I told the officer I was a doctor and that I was there to help. He was kind enough to direct me to the Jacob Javits Center [on 34th Street, approximately 4 miles from where the Twin Towers had stood]. I can remember how eerie it was driving through that tunnel alone, with no other cars on the road. Anyone who lives in New York City can tell you that never happens.

When I pulled up in front of the Jacob Javits Center, a tall man in fatigues asked me, "Are you the chiropractor?" Stunned, I said, "Oh, yes, I am," but in my mind I was wondering how he knew I was coming. Later, I found out that he was likely waiting for Dr. John Albaneze, who arrived a few hours after me. The doctor who greeted me was Dr. Hernando Garzon, chief medical officer for FEMA; he and his staff helped us unload our vehicle. They set us up upstairs at the Jacob Javits Center and told us that most of the FEMA search-and-rescue workers would return about 7 a.m.

At this point, a lot of my memory is a blur. (I apologize if I leave anyone out or get anything incorrect; after all, it's been 10 years.) The Javits Center was full of search-and-rescue teams that were still pouring in from all around the country and even from around the world. Then the patients started coming, Dr. Albaneze showed up and we worked through the night. I remember Mick Sacco, the friend I'd brought with me, running back and forth between the FEMA search-and-rescue workers and the news media, expressing the needs of the different teams. It was astonishing how quickly those needs were met. I think it was something like 3 a.m. when he put a call out over the air for blowdryers to dry the search-and-rescue dogs. Some hair supply place brought them right over; that's just how it was. People just gave.

Throughout that night and the next morning, more chiropractors showed up, as did massage therapists and acupuncturists. On occasion I would ask Dr. Garzone when it would be alright for me to go down to "The Pile" – that's what we called the smoking mass of twisted metal and remains. By the next evening, the Javits Center was fully stocked with chiropractors full of passion and desire to help.

At 7 p.m. that evening, I was given the go-ahead to work my way down through five checkpoints to The Pile. Just before I left, I remember seeing a U.S. marshal passed out on some folding chairs. She had been up for over 40 hours. I remember handing her a pillow.

At the first checkpoint, NYPD-manned, no one wanted to hear from me. One officer noticed my frustration. Yolanda Gutierrez was her name. Already up for more than 24 hours, she sat me down, called back to FEMA and was able to verify my clearance. While this was happening, a very kind woman had filled the Jeep Cherokee I was driving with trays upon trays of food she had cooked out on the sidewalk. She begged me to bring it to the men working.

The next few checkpoints were manned by U.S. marshals and went smoothly. The checkpoint with the military police was a different story. By this time, the smoke from the pile had mixed with the lights, creating an eerie fog. Our only identification at this moment was our driver's license with a sticker placed on it by FEMA. That's it, just a silly colored circular sticker placed over the driver's license. After the MP removed his weapon from my face, my friend and I explained our purpose and our clearance. The MP grumbled that our IDs were subpar, but after a thorough searching, he reluctantly let us through.

It was well after midnight by the time we made it through all the checkpoints. Our first impression was the smell; oh, how I will never forget that smell. Beyond that, our inability to see due to the thick smoke and all the different uniforms rushing around created a sensation that was unreal. We always said it felt like we were on a movie set where King Kong was battling Godzilla in Manhattan.

We parked in front of St. Peter's Church on the corner of Church and Vesey. The Salvation Army had already set up a canteen – essentially a cafeteria – and was stacking supplies on the church steps. Later, it would be the Salvation Army that helped us and fed us and clothed us. I carried what few supplies I had left and my portable chiropractic table into the church. I was happy to see that the Salvation Army had already set up a medical supply on the church pews. I set my table up between the pews and noticed how eerie the altar looked. It was covered in at least an inch of dust/ash. Later, there would be a book on the altar that many signed and left behind their fear, hurt, fatigue and memories.

I remember walking in that dust; it looked like we were on the surface of the moon. I was later told that the church had been completely locked and sealed during the towers' collapse, yet great amounts of dust still made it in. Mick and I ran outside to see who we could help. We had no hardhats and no masks, so the Salvation Army supplied us. As we walked up Church Street, we came to the St. Paul's Church graveyard. There isn't enough room in this story to describe how, little by little, your eye catches glances of things and over time begins to make them out; how surreal everything seems. I remember horizontal blinds in the trees, which had been knocked over, and how everything was covered in dust. Along the fence were small tents and a Salvation Army canteen. There were large overhead lights that gave everything a odd, movie-like feel.

The attitude at the site can't be emphasized enough. It was solemn yet busy, but with an air of hope. There was no smiling, no emotion; just work – and you dared not have a camera. I saw a news cameraman trying to sneak around and they picked him up and threw him out of the site. This was not a place of discovery, journalism or interest; not then. This was the place where so many of these people had lost someone. These men lost brothers and sisters. They were working nonstop for days. The FDNY is a fraternity that you can't describe. They had one thing on their minds: rescue whoever could be saved. They stuck together like a pack of vicious wolves and protected the lives, integrity and honor of their own.

As we walked, we walked lightly, making sure to hide our natural intrigue. We could see the damage to building five by this point; the exterior facade of the building was warped and twisted, and all the glass was gone. It was here that I would later meet Officer Gail Imhauser. She was a transit cop who told me of her plight and how she had been saved by a brave fireman. Gail, along with many others, ran inside building five to take cover from the falling debris. She told me the dust was so aggressive that although she squeezed her eyes, nose and mouth shut and covered her face, she still choked on a ball of dust that lodged in the back of her throat. The fireman who had taken cover with her and some of his fellow firefighters used their axes to break them out of the building and ultimately saved their lives.

Over time, Gail and I would become good friends, and she would lead many people to our makeshift clinics for chiropractic care. She would also give me a call and ask me to meet her and some fellow police officers who were not allowed to take a break or even remove their bulletproof vests. She would have me meet them in building lobbies, alleyways and even dining halls to receive treatment.

Prior to 9/11, Officer Gail was not a chiropractic patient. But in the aftermath of 9/11, she saw the results chiropractic provided firsthand and wanted her colleagues to experience the benefits of chiropractic care. I have a miniature version of her badge here in my hand right now as I write this. I'm thankful for her friendship and the hundreds of other friends and heroes I met.

As Mick and I kept walking to our right, the remains of building seven could be seen down the alleyway. We were able to make it within 50 yards of the Millennium Hotel, and it was from this vantage point that we could make out the facade of WTC building 2 through the smoke. A portion of the remains was stuck in the ground like a lawn dart; later, Officer Gail would inform me that it had pierced the ground more than 60 feet, and if I remember correctly, penetrated into one of the train tunnels.

Sometime in the early-morning hours while it was still dark, I noticed a passed-out fireman lying on an I-beam. Smoke was pouring out all around him. I shook him and told him I was a doctor. I asked him to come back with me to the makeshift clinic we had made in the church. He didn't want anything to do with me; he did not want to be taken off the pile and away from his brothers, whose rescue alarms (known as PASS devices) we could hear going off underneath the wreckage.

I expressed to him that I was chiropractor and that I might be able to help him. I brought him back to the church, assessed and adjusted him. He got a burst of energy and thanked me. Later, he sent me hundreds of patients.

Before the 7 a.m. shift started at the Javits Center, I had adjusted well over 100 people. I would eventually see patients with injuries of all types including puncture wounds, impalements, and even two heart attacks.

If you read the stories on the Internet from other chiropractors who volunteered at Ground Zero, you know they were working nonstop as well. Together, we began what I have to say was the most effective broad-based and extensively used chiropractic-only health care emergency response in this nation's history. On top of that, it was all volunteers! The patients simply did not want to go to the medical tents. It brings a smile to my face, and I hope to yours, knowing that we did it. The police, firefighters, U.S. marshals, military police, FEMA teams, city cleanup crews, transit authority workers, engineers, city council members, and on and on chose chiropractic care. I worked on that pile until Dec. 18, 2001, and have so many memories. I'm very proud to be a chiropractor.

In part 2 of this article (Sept. 23 issue), Dr. Gorgo recounts how he was recruited by FEMA to credential and train chiropractic volutneers, and how together, they continued to make a difference in the lives of so many in the aftermath of Sept. 11.