It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

The 2003 Meeting of the American Back Society, Part II

[Editor's note: Part I of this article appeared in the April 22 issue.]

Hoban's Posteriority Workshop

Physiotherapist Patrick Hoban, if we forgive his obsession with denouncing cavitation events, put on a very interesting and clinically useful workshop on muscle energy techniques (METs) and articular mobilizations of the thoracic spine and ribs. And had it not been for his Byzantine listing system, compared with which chiropractic listings seem virtually colloquial, Hoban could have passed for a chiropractor: Using volunteers from the audience, he found the subluxation, fixed it, and left it alone - and even got an "audible," much to his chagrin, given his distaste for them. He considers T4 and first rib lesions the most commonly seen, and implored us, if we got nothing else out of his workshop, to go to work the proverbial next Monday morning and start fixing them on every patient.

As I write this, I am looking at a spiral-bound, well-illustrated, 24-page workbook handed out at the workshop - about as good as it gets for a symposium presentation. The thoracic screen begins with palpating a seated patient for posteriorities and anteriorities, using the flats of the hands placed so as to span either the transverse processes or the ribs. As examples of thoracic "lesions," we find a posterior transverse process on the right, whereupon we flex and extend the patient to see what happens at end range.

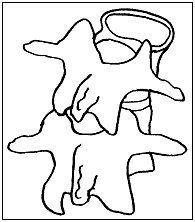

Hoban's claim is that if he were to palpate a posteriority of the right transverse process, one of two things would happen during motion palpation: Either the left joint would fail to move backward during extension (a flexed lesion: FRSR = Flexed Rotated Side-bent to the Right) or the right joint would fail to move forward in flexion (an extended lesion: ERSR = Extended Rotated Side-bent to the Right). The illustration below represents the end-range configuration in either case. Of course, it also shows what would be called a PLS, using Gonstead nomenclature: the superior vertebra is laterally flexed to the right, and its spinous process is rotated to the left. Despite the pictorial similarity, the Gonstead PLS is a static misalignment, whereas Hoban's lesions represent left-right motion asymmetries that develop in either flexion or extension at end range.

This work is a great leap forward, in that it connects the worlds of static and motion palpation: a posterior TP on the right predicts either left-sided extension restriction or right-sided forward flexion restriction. Moreover, unlike typical motion palpation procedures, we at least try to ascertain whether it is the right or left facetal joint that is restricted. The nomenclature, on the other hand, is a great leap backward, and may have confounded even Dynamic Chiropractictm readers. Restrictions, which should be identified by the direction of movement that is lacking, are instead named by the opposite direction; e.g., Hoban calls an extension restriction a "flexion lesion."

To correct lesions, Hoban uses one arm to passively and gradually bring the seated patient's trunk into the restricted direction, while his other hand palpates the transverse processes of the posterior segment. This muscle energy technique is a direct technique, meaning the treatment is always in the direction of restriction. In addition, lesions are treated with a series of three isometric muscle contractions, in which the therapist or doctor opposes the patient's attempt to move opposite the direction of restriction (a well-known PNF procedure).

Nucleoplasty: Repair of Disc Degeneration With Injections

The pathophysiology of discogenic back pain continues to engender debate, with biomechanical and biochemical models seeming relevant. Dr. Connor O'Neill believes that the apparent success of surgical procedures that remove disc material, although at first glance seeming to support a biomechanical model, may be explained in another way. He and his colleagues found changes in interleukin levels in surgical patients, suggesting that surgery may inaugurate a tissue repair process promoted as much or more by these and other cytokines than by the discectomy itself.

If this were true, it would follow that a prudent physician could just skip the surgery and attempt to directly produce chemical, generally anti-inflammatory changes in the spine, to recover discs biologically. Dr. O'Neill is doing just that - treating discogenic pain by injecting the disc with glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, over-the-counter supplements shown to reduce arthritic symptoms, and preserve or even promote regeneration of cartilage. He recently reported the preliminary results of a clinical study (Klein, 2003 #1719) - OK, no controls, no blinding, no randomization - but the patients did seem better off, in that their Roland-Morris and VAS pain scores improved. The investigators did not report whether there had been a demonstrable structural change, in addition to the apparent subjective benefit derived by the patients.

Donelson: Line of Drive Does Matter!

For all the emphasis on getting the right listing in chiropractic, there is little evidence that getting the right "listing" has much impact on the outcome of care. We don't know if adjusting the "right" way gets a better outcome than adjusting the "wrong" way. Indeed, there is evidence that cervical manipulation according to motion palpation findings does not result in a better outcome than random cervical manipulation.1

Enter McKenzie advocate Ronald Donelson, who has figured prominently in many of my ABS conference reviews over the years. He reviewed some of the evidence leading to the sweeping conclusion that the key to improvements in the care of low back pain is subtyping of otherwise similar patients into groups likely to respond (or not) to different interventions. The unflattering outcome of some randomized trials may result from the unwarranted assumption that all patients with "nonspecific" low back pain are essentially the same. Subgroup identification is the holy grail of RCTs; that is, it is foundational for clinical decision-making, predicting outcomes, and understanding the disease process.

Clinical trials in which patients are randomly assigned to "right" and "wrong" treatments always seem alarming; how ethical is it to assign patients to apparently wrong treatments? But that's just it. Although there is abundant evidence that patients performing exercises that are concordant with McKenzie directional preference criteria improve clinically, this does not preclude the possibility that performing disconcordant exercises could have obtained a similar outcome. Therefore, until this study, there was no scientific evidence distinguishing right from wrong McKenzie exercises.

Researchers Donelson and Audrey Long subtyped 312 patients with acute and chronic LBP, with and without leg pain, into two subgroups; 230 of the subjects showed directional preference, with centralization of symptoms in extension (83%), flexion (7%), or lateral flexion (10%). These patients were then randomly assigned to receive directionally matched treatment, directionally unmatched treatment, or a nondirectional exercise protocol. Although all three treatment groups showed improvement, the group that performed exercises concordant with directional preference did best, with 95% improvement, compared to 42% in the general exercise group and only 23% improvement in the disconcordant group.

This is both clinically and statistically a very significant finding. Further, no one in the "matched" group withdrew due to either no improvement or worsening. Indeed, no one in the matched group worsened, while 15% of both the unmatched and nondirectional groups did. It is further remarkable that 15% of these centralizing patients with a directional preference, who by every other study should have had a very favorable outcome, were, instead, actually worsened by the two nonmatched treatments!

That stated, it remains worth noting that 85% of those subjects receiving the "wrong" treatment were not worsened. I have been saying for quite some time that when it comes to adjusting according to chiropractic listings, doing the right thing is better than doing the wrong thing, but doing the wrong thing is still better than doing nothing. (i.e., not getting adjusted). The McKenzie protocol partially supports that hypothesis, although it partially refutes it as well. Since most studies only report on the group mean, we never learn how many were actually worsened by a treatment. We must stop generalizing based on group means. We treat individual patients, not means. That's why an assessment into validated subgroups to select the best treatment is so vital.

(Author's note: Dr. Donelson reviewed the above section of my report for accuracy.)

Dr. Haldeman's Keynote Address

Delivering the final presentation of the general sessions, Dr. Haldeman, MD, PhD, DC, the consummate interdis-ciplinarian in the most interdisciplinary of all back organizations, was the perfect choice to define the central questions addressed by this symposium. Haldeman listed over two dozen treatment approaches featured during this conference alone, very few of which are shown by the scientific literature to show any advantage over any other for representative conditions.

The program abstract for his talk points out an interesting juxtaposition of facts: Almost everyone at some point in their life experiences back pain, and 90 percent of the population develops pathological changes in their spine, often with only minor pain symptoms. The nonequivalency of pain and structural change mandates renewed emphasis on nonsurgical approaches to most clinical situations. Providers need to be realistic with their patients, since there is no guarantee that any approach, surgical or nonsurgical, will eliminate pain, although it is fair to expect at least short-term pain reduction.

Reference

- Haas M, Groupp E, Panzer D, Partna L, Lumsden S, Aickin M. Efficacy of cervical endplay assessment as an indicator for spinal manipulation. Spine 2003;28(11):1 091-6; discussion 1,096.

Dr. Robert Cooperstein, a professor at Palmer College of Chiropractic West, can be reached at www.chiroaccess.com, or by e-mail at drrcoop@aol.com.