Some doctors thrive in a personality-based clinic and have a loyal following no matter what services or equipment they offer, but for most chiropractic offices who are trying to grow and expand, new equipment purchases help us stay relevant and continue to service our client base in the best, most up-to-date manner possible. So, regarding equipment purchasing: should you lease, get a bank loan, or pay cash?

Frequency and Duration of Care: Proposed Algorithms for Enhanced Understanding of Contemporary Chiropractic Guidelines

Note: This is an attempt to interpret Chapter 8 of Guidelines for Chiropractic Quality Assurance and Practice Parameters, (Aspen Publ. 1993). The reader is warned that this article is an extract or part only of a major publication suggesting guidelines for the practice of chiropractic. Any part of the publication is likely to be confusing and/or misinterpreted unless read in the context of the full document, which includes detailed commentary, definitions, literature review, and explanation of rating systems used. It is recommended that you obtain a copy of the full publication.

At first glance, the chapter of the Mercy Guidelines1 dealing with frequency and duration of chiropractic care may be very confusing and has a high likelihood of being misinterpreted. We have already heard statements from some critics that the Mercy Guidelines will limit chiropractic care to "12 visits" or "four weeks" per condition, or that it is putting chiropractic in the "low back pain box." Despite the complexity of the chapter and all of this rampant misinformation, there are other influences that make this chapter a hot topic.

Of all the committees assembled in the development of this document, Chapter 8 on "Frequency and Duration of Care" was likely to be scrutinized the most as it is probably the most sensitive issue surrounding discussions of standards and guidelines. The controversy on how long and how often a chiropractor should manage a patient's condition is a focus of internal strife and external mistrust. All of this consternation is because our profession is comprised of so many differing opinions, technique interests, and economic motivations.2 Add to that the continual conflict seen between practitioners and a health care industry that has tried hundreds of various reimbursement schemes for chiropractic services. Unfortunately we do not have adequate data or published reports that sustain the various contentions of each of these interest groups.

The chiropractic profession is not the only health care profession that is going through this kind of guideline development. One of the major reasons why all of the health care professions are being steered into producing guidelines is because there are demonstrable variations in practice. This phenomenon has been demonstrated in the medical profession for over 20 years, with recent evidence showing that as much as 70 percent of spinal surgery is unnecessary. The list of medical procedures (both diagnostic and therapeutic) that show significant variations in practice continues to grow as further inquiry into medical effectiveness matures.

There has also been study in the chiropractic profession that demonstrates variations in duration, frequency and costs of care.3,4,5 And just like our medical/surgical counterparts, we are now being scrutinized for these variations. The reason why studying variations in practice is so important, is the high correlation between practice variation and escalating health care costs. The chiropractic profession is now the third largest health profession, so we can expect to be scrutinized for appropriateness of our varied array of services. This is especially true now that we are being considered for inclusion in various government-sponsored health programs.

For the chiropractic profession, the Mercy Guidelines serve as an important "first step" to inventory chiropractic science and common elements of general practice, and also serve as a foundation for future critical dialogue in health services research and health care administration. In Chapter 8, the document addresses the issue of frequency and duration of care. Here, the reader will find important definitions of related terms, description of time-course and natural history, a well-written literature review, and nine guidelines or "recommendations" to generally judge appropriateness of chiropractic methods for the more uncomplicated case presentations. You will note that there is an emphasis on management considerations for uncomplicated patient presentations. The strength of these recommendations comes largely from a recent controlled study in chiropractic management of uncomplicated back and neck complaints.6

To date, there has not been sufficient critical study that allows us the ability to generalize on appropriateness issues (of frequency and duration) relative to complex clinical presentations including trauma management. As such, our profession has to rely on anecdotal expert offerings, results of case studies, or protocol by convention. Until there is significant controlled study into these more complex issues, we will have to depend on consensus of expert opinion which has a lower "weight of evidence" in such formal guideline development.

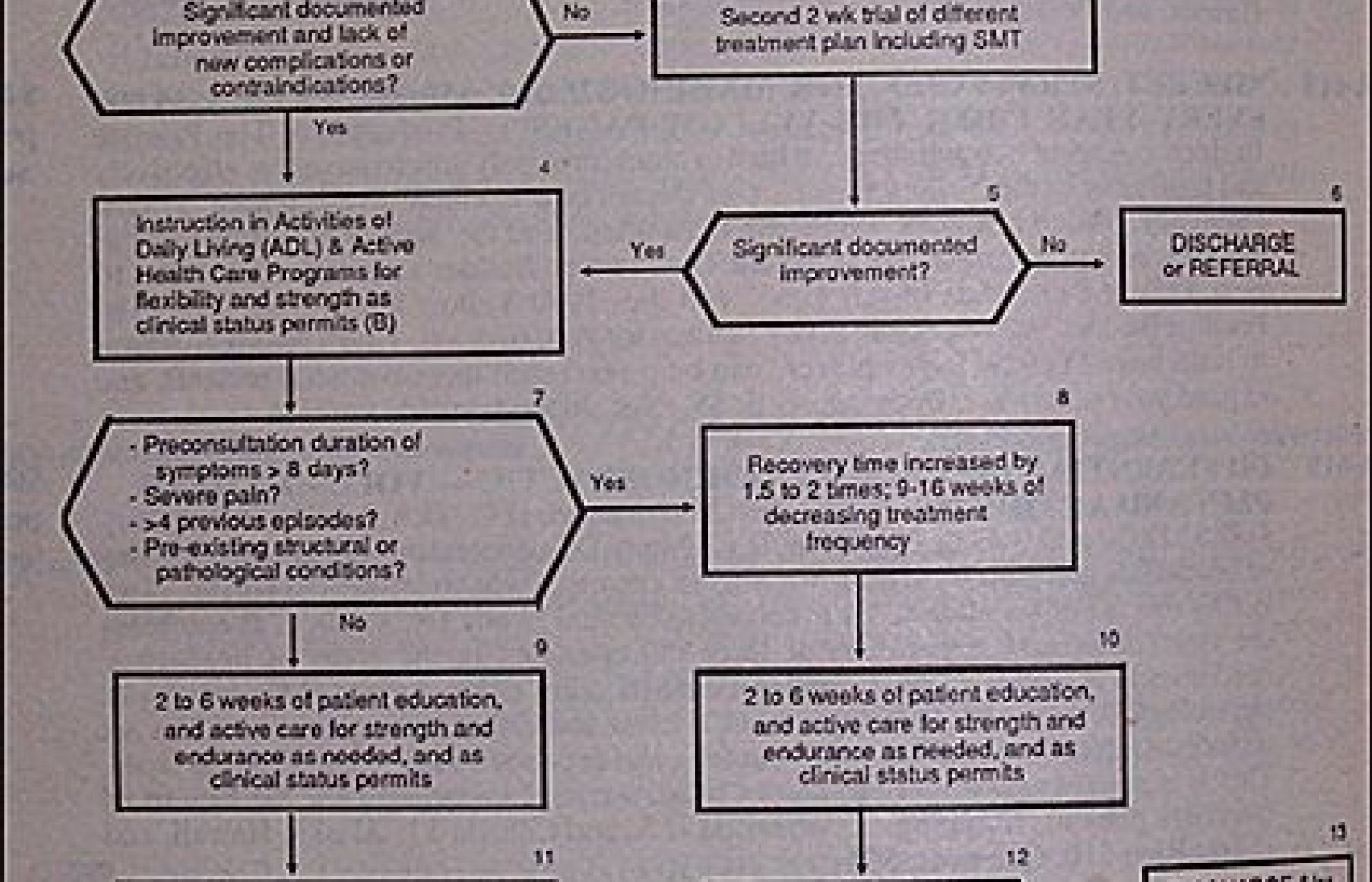

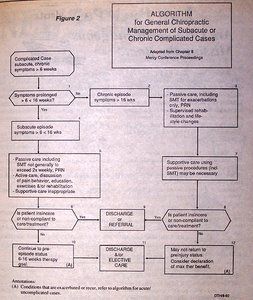

The essential elements of the recommendations can be collapsed into decision sequences or "algorithms," depending if the case is acute (Figure 1) or subacute/chronic (Figure 2). By following along the respective algorithm, there is likely to be a better understanding of the Chapter 8 recommendations. A summary of where the specific recommendations end up in the various algorithm "boxes" is found in Table 1. It should also be understood that these algorithms are designed to assist clinicians by providing a framework for the treatment of the more common patient problems confronting the chiropractic physician. They are not intended to replace either the clinician's clinical judgment or to establish protocol for all patients with a particular condition. It should also be understood that some patients will not fit the clinical conditions contemplated by such guidelines, and that a guideline will rarely establish the only appropriate approach to the problem.

This article is the first time these two algorithms have been published and disseminated profession-wide through print media. Initially, they were distributed as a part of a guideline pilot project where data was gathered to see if learning tools such as algorithms will have any impact on implementation and physician compliance.7 The results of this study will be reported to the chiropractic profession at future research symposia.

You are encouraged to use these algorithms to help understand some of the contextual nuances of the Chapter 8 recommendations. Keep in mind that just like all the recommendations in the Mercy Guidelines, these algorithms are begging for critical discourse and improvement. Use of guidelines and flow charts is a reasonable attempt to identify appropriateness for chiropractic services for certain uncomplicated presentations, and thus can potentially minimize variation in the delivery of those services. When the profession can demonstrate some control on those variations, we can assure cost-effective purchasing of our essential services.

In the future, you will likely find similar algorithms in chiropractic journals, textbooks, and postgraduate programs. They are useful tools for summarizing management of some of the more common clinical presentations confronting chiropractic practitioners.8,9

References

- Haldeman S, Chapman-Smith D, Petersen DM, Eds: Guidelines for Chiropractic Quality Assurance and Practice Parameters. Aspen Publishers, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD., 1993.

- Jansen RD: A survey of American chiropractors' attitudes toward practice standards and the organizations developing them. Proceedings of the International Conference on Spinal Manipulation. Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research, Arlington, VA., 1992.

- Shekelle PG, Brook RH: A community-based study of the use of chiropractic services. Am J Pub Health, 81(4):439-442, 1991.

- Jarvis KB, Phillips RB: Managed care and its impact on the cost per case comparison of Utah Workers' Compensation back injuries treated by three chiropractic subgroups in two different years. Proceedings of the International Conference on Spinal Manipulation. Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research, Arlington, VA., 255-57:1991.

- Hansen DT: Chiropractic physicians' practice patterns: A case study. Proceedings of the International Conference on Spinal Manipulation. Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research. Arlington, VA., 258-61, 1991.

- Triano JJ, Hondras MA, McGregor M: Differences in treatment history with manipulation for acute, subacute, chronic, and recurrent spine pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther., 15(1):24-30, 1992.

- Hansen DT, Osterbauer PJ, Fuhr AW, Dressler LM, Jansen RD: Implementation of chiropractic guidelines: a prospective pilot study. Platform presentation at the International Conference on Spinal Manipulation. Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research. Montreal. 1993.

- Hansen DT: Development and use of clinical algorithms in chiropractic. J Manipulative Physiol Ther., 14(8):478-482, 1991.

- Adams AH, Triana AD: The identification of priority health care conditions in a contemporary-based, problem-centered curriculum. Proceedings of the International Conference on Spinal Manipulation. Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research. Arlington, VA., 265:1991.

Daniel T. Hansen, DC, FICC

Olympia, Washington

Table 1 | ||

Algorithmic distribution of recommendations | ||

| Recommendation | Box# | Annotation |

| Acute care algorithm (Figure 1) | ||

| 8.1.1 Short/long range treatment planning | 7,8 | |

| 8.2.1 Treatment/care frequency | (A) | |

| 8.4.1 Failure to meet treatment/care objectives | 1,2,3,5,6 | |

| 8.5.1 Uncomplicated cases: acute | 1,4,11 | (B)(C) |

| 8.7.1 Elective care | 13 | |

| Subacute/Chronic care algorithm (Figure 2) | ||

| 8.3.1 Patient cooperation | 6,8,9 | |

| 8.4.1 Failure to meet treatment/care objectives | 3,7 | |

| 8.6.1 Complicated cases: signs of chronicity | 3,5 | |

| 8.6.2 Complicated cases: subacute episode | 3,12 | |

| 8.6.3 Complicated cases: chronic episode | 11 | |

Daniel T. Hansen, DC, FICC

Olympia, Washington