It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

Exercising the Rotator Cuff - Minus the Deltoid

The rotator cuff acts in concert with the deltoid to elevate the shoulder. An important function of the cuff muscles is to keep the head of the humerus centered within the glenoid cavity (concavity compression), and at the same time, to impose an inferiorly directed force vector to the humeral head. The chief compressor is the supraspinatus, while the teres minor, infraspinatus and subscapularis also act as compressors, but also provide an inferior force to keep the humeral head from shearing upward during arm elevation. This function is crucial; if the humeral head is not maintained adequately within the glenoid, normal deltoid contraction will cause a superior translation and an upward shearing of the head to the acromion and coracoacromial ligament above.

Frequently, rotator cuff lesions are caused by intrasubstance degenerative tearing, or tendinosis due to avascularity, aging or overuse. Other potential causes include trauma, outlet stenosis or glenohumeral instability.1 These types of lesions result in weakness of the cuff muscles - especially the supraspinatus, which lose their ability to oppose the superior migration of the humeral head with active elevation of the arm. This superior migration functionally narrows the subacromial space; eventually, the greater tuberosity and the rotator cuff abut against the under-surface of the acromion and the coracoacromial ligament, leading to what is known as "secondary impingement." The articular side of the supraspinatus and the anterior infraspinatus insertion also is at risk, because it has a poorer blood supply than the bursal side.2 "Primary impingement" is an extrinsic force directed to the superior portion or bursal side of the cuff, and is not nearly as common as secondary impingement.

Morrison3 stated that the basis of rotator-cuff disorders is a muscle imbalance between the elevators and depressors of the humeral head (the deltoid and the rotator cuff). He further stated that as a natural part of aging, the deltoid retains its strength longer than the relatively diminutive rotator cuff, resulting in a loss of the depressor effect of the rotator cuff on the humeral head during elevation, leading to subsequent impingement. Even normal shoulders, when overloaded and fatigued, as in swimmers; players of racquet or throwing sports; or those with occupational demands, have been found to fatigue the cuff muscles, resulting in superior migration of the humeral head. This migration results in lesions on the underside (articular) portion of the cuff, and also may be responsible for lesions on the bursal side of the cuff.

Burkhead2 found that the type-3 acromion, which has a hook that impinges on the bursal side of the cuff, often is not an abnormal acromion, but a traction spur of the coracoacroial ligament caused by the repetitive superior migration of the humeral head overloading the ligament. The coracoa cromial ligament functions as a stabilizer against the superior migration of the humeral head.

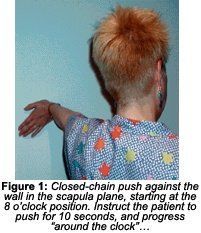

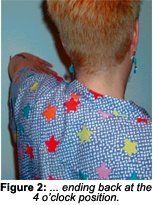

All of the above evidence demonstrates that weakness of the cuff should be avoided, especially in the early stages of a tendinosis-type problem, and that exercises should be prescribed that strengthen the cuff muscles with minimal or no contraction of the deltoid muscle. Kibler4 recommended closed-chain exercises, in which the distal part of the segment is fixed and movement occurs at the proximal segment, for example, the knee is exercised with the foot on the ground. In an open chain, the distal segment moves in space. With a closed-chain shoulder exercise (See Figures 1 and 2) performed in the scapular plane (with the arm about 30 degrees anterior to the coronal plane), there is proper scapular position and stability, allowing the rotator cuff to work as a "compressor cuff," conferring concavity compression and a stable instant center of rotation.

Figures 1 and 2 (page 30) show a patient pushing against the wall with the shoulder in the scapular plane with the hands starting at "8 o'clock," and progressing to "4 o'clock." Pressure is exerted against the wall at 10-second intervals, moving up to the 4 o'clock position. This allows for rotation of the humerus with the arm at 90 degrees of abduction, which replicates rotator cuff activity from extreme internal to extreme external rotation, activating all of the cuff muscles. Before activating the cuff muscles, you can activate the scapular stabilizers by instructing the patient to place his or her arm and hand at the 12 o'clock position (with the arm in the same closed-chain position) and retract, protract, elevate and depress the scapula.

References

- Budoff J, Nirschl R, Guidi E. Debridement of partial-thickness tears of the rotator cuff without acromioplasty. J Bone and Joint Surg 1998;80A(5)1998.

- Rothman RH, Parke WW. The vascular anatomy of the rotator cuff. Clin. Orthop 1965;41;176-186.

- Burkhead W, Morrison DS, et al. Symposium: the rotator cuff: debridement versus repair-part II. Contem Orthop 1995;31;313-326. In: Budoff J, Nirschl R, Guidi E. Debridement of partial-thickness tears of the rotator cuff without acromioplasty. J Bone and Joint Surg 1998;80A(5).

- Kibler BW. Shoulder rehabilitation: principles and practice. Med and Sci Sports Exerc 1999;30;S40-S50.

Warren Hammer, MS, DC, DABCO

Norwalk, Connecticut

softissu@optonline.net