It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

The Challenge of Knee OA and the Potential of Manual Therapy

Knee osteoarthritis is a major public health problem that primarily affects the elderly. Almost 10 percent of the United States population suffers from symptomatic knee osteoarthritis by the age of 60. In fact, OA is prevalent worldwide, especially with an increasingly aging society. It is one of the leading causes of pain and dysfunction in the joints among the aging population.1 Despite this, there are no approved interventions that ameliorate structural progression of this disorder.

OA is a degenerative joint disorder characterized by articular cartilage degradation, osteophyte formation, synovium hyperplasia, subchondral bone cysts and sclerosis. Its pathogenesis remains unclear, making it a challenge to manage. Even with all the technological advances in imaging and improvements in joint replacements, we are lacking effective nonsurgical methods of management, especially in the early stages of the disease. As far as prevention and or preventing progression, there are no practical options.

Diagnosis: A Major Challenge

At present, the diagnosis of OA of the knee primarily depends on clinical symptoms and radiographic findings. Conventional radiography is still being used as a standard imaging technique for the evaluation of known or suspected OA in clinical practice and research. (Figure 1)

Kellgren-Lawrence radiographic grading criteria is generally the assessment tool used in the evaluation of OA in the knee. This is a problem because most individuals are clinically asymptomatic in the early stages of OA, and often pathological degradation of the articular cartilage already exists before the symptoms arise.

Thus far, epidemiological, or clinical studies of knee OA depend largely on the radiographic definition. Even when the same grading criteria is used, the scoring varies between observers.2 Because of these issues, one must assume that we are missing potentially many people with OA, making the true prevalence of this condition underestimated.3

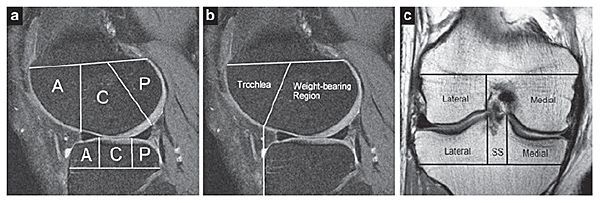

MRI demonstrates pathological changes much earlier than conventional radiography. Two semiquantitative scoring systems are commonly used for assessing the prevalence and severity of morphologic cartilage lesions, meniscal damage and bone marrow lesions (BMLs) from MRI of knees with osteoarthritis. One is referred to as the Whole Organ MR Scoring (WORMS); the other the Boston-Leeds OA Knee Scoring (BLOKS). (Figure 2)

However, even though MRI-based studies detect knee OA earlier in comparison to conventional radiography, it remains unknown whether even these findings represent the initial stages of the disease. Clinical symptoms are often not present initially, and even patients with no clinical symptoms will demonstrate MRI findings when the conventional radiographs are normal. Therefore, even the diagnostic methods currently in use have limitations in detecting preclinical OA and do not provide an accurate assessment of disease progression.

It is still unknown whether just imaging the joint and finding abnormalities without clinical symptoms represents the initial stages of early disease. Therefore, the clinical diagnosis of early OA is one of the greatest challenges in musculoskeletal disease.6

Advances in proteomic technologies have facilitated extensive proteomic characterization of various body fluids and evaluating the synovial fluid in direct contact with articular cartilage, synovium, ligament, meniscus, and joint capsule. Alterations in metabolism of any of these tissues during disease progression are reflected as alterations in the proteomic profile.7

To date, however, there appears to be no standardization of what the normal and abnormal biomarkers are that are associated with OA.8 Researchers are still attempting to tease out the pathogenesis of this degenerative process.

Treatment: Just as Challenging

There are no approved interventions that will ameliorate the structural deterioration and progression of the disease. Yes, there is joint replacement surgery, but I would not consider this treatment a very practical method, as it generally requires clinical symptoms to be debilitating enough to require the removal of the joint to regain function.

There are other "treatments," such as injectables; but to date I have yet to see any definitive study that would truly represent regenerative therapy. This includes viscosupplementation, platelet-rich plasma, prolotherapy and even stem-cell therapy. These therapies do not slow the progression of the disease or repair the damage to the cartilage. They are presently utilized to temporarily alleviate symptoms.

Stem cells, exosomes and genes seem to hold some promise for regenerating cartilage, but these therapies are in the early stages of experimentation. Without a way of accessing the early changes caused by OA before degenerative changes begin to destroy the cartilage, when should treatment be started to avoid progression of the disease?9 We are still at the stage of symptomatic relief.

So, What's the Takeaway?

The definition and diagnosis of OA is evolving with improvements in risk-factor measurement, using advanced imaging, systemic and local biomarkers and improved methods for measuring symptoms, which help to understand the mechanisms and identify potential areas for intervention or prevention. Regenerative medicine, despite tremendous interest, has yet to able to demonstrate the efficacy of this modality for definitive structural improvement that would last for years or decades, and obviate or delay the need for joint arthroplasty.

All these modalities are still only symptomatic relief, which don't seem to justify the high cost. We are still just managing the symptoms, rather than reducing disease progression. So, why not take a more conservative biomechanical approach than surgery, at least in the earlier stages of disease? Not everyone needs a joint placement, and they don't come with a warranty.

Chiropractic Intervention

Manual therapy, which includes joint mobilization and manipulation, combined with stretching and strengthening exercises to affect the components of the full kinematic chain of the lower extremity, including the lumbar segments, has proven beneficial.10-11 This is a form of conservative biomechanical therapy – really a chiropractic treatment. This type of manual therapy, along with exercise, muscle strengthening, and nutritional / weight-management consulting, should be an option for most patients, particularly in the earlier stages of disease (Kellgren Grade 1-3).12-13

Research on the clinical efficacy of chiropractic manual therapy techniques for the spine is well-documented.14 However, much less attention has been focused on chiropractic interventions directed toward the peripheral joints. Individualized manual therapy, along with the prescription of an aerobic walking and quadriceps-strengthening exercise program, has been documented to significantly improve knee pain and function.15

Application of chiropractic knee techniques can significantly reduce the symptoms associated with knee OA.16 Macquarie Injury Management Group Knee Protocol (MIMG) is a chiropractic approach that includes two techniques: myofascial mobilization and myofascial manipulation.17 It was introduced by the MIMG group, Australia. The protocol consists of a noninvasive myofascial mobilization procedure and an impulse thrust procedure specific to the patellofemoral articulation. Maitland and Mulligan mobilizations are two other protocols used in osteoarthritis treatment.18-19

The takeaway: Much can be offered with manual therapy for the patient who has good bony and ligamentous integrity, but also happens to suffer from osteoarthritis of the knee.

Editor's Note: To read an article with the best description of the MIMG protocol used for knee OA, Dr. Pate suggests www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2597887/.

References

- Neogi T. The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarth Cartilage, 2013;21(9):1145-1153.

- Guermazi A, Hunter DJ, Li L, et al. Different thresholds for detecting osteophytes and joint space narrowing exist between the site investigators and the centralized reader in a multicenter knee osteoarthritis study - data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Skeletal Radiol, 2012 Feb;41(2):179-86.

- Sanghi D, Avasthi S, Mishra A, et al. Is radiology a determinant of pain, stiffness, and functional disability in knee osteoarthritis? A cross-sectional study. J Orthop Sci, 2011 Nov;16(6):719-25.

- Kohn MD, Sassoon AA, Fernando ND. Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence classification of osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2016;474(8):1886-1893.

- Lynch JA, Roemer FW, Nevitt MC, et al. Comparison of BLOKS and WORMS scoring systems part I. Cross sectional comparison of methods to assess cartilage morphology, meniscal damage and bone marrow lesions on knee MRI: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarth Cartilage, 2010 Nov;18(11):1393-401.

- Arnscheidt C, Meder A, Rolauffs B. [Early diagnosis of osteoarthritis: clinical reality and promising experimental techniques]. Z Orthop Unfall (German), 2016 Jun;154(3):254-68.

- Liao W, et al. Proteomic analysis of synovial fluid in osteoarthritis using SWATH–mass spectrometry. Molec Med Rep, 2018 Feb;17(2):2827-2836.

- Duan Y, Hao D, Li M, et al. Increased synovial fluid visfatin is positively linked to cartilage degradation biomarkers in osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int, 2012 Apr;32(4):985-90.

- Im GI. Current status of regenerative medicine in osteoarthritis. Bone Joint Res, 2021;10(2):134-136.

- Deyle GD, et al. Physical therapy treatment effectiveness for osteoarthritis of knee: a randomized comparison of supervised clinical exercise and manual therapy procedures vs. a home exercise program. Phys Ther, 2005 Dec;85(12):1301-17.

- Tsokanos A, Livieratou E, Billis E, et al. The efficacy of manual therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Medicina, 2021;57(7):696.

- Young JJ, Vazié O, Cregg AC. Management of knee and hip osteoarthritis: an opportunity for the Canadian chiropractic profession. J Can Chiropr Assoc, 2021;65(1):6-13.

- Skou ST, Roos EM. Good Life with osteoarthritis in Denmark (GLA:D™): evidence-based education and supervised neuromuscular exercise delivered by certified physiotherapists nationwide. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2017;18(1):72.

- Nelson CF, Lawrence DJ, Triano JJ, et al. Chiropractic as spine care: a model for the profession. Chiropr Osteopat, 2005;13:9.

- Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M. Aerobic walking or strengthening exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee? A systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis, 2005;64(4):544–548.

- Pollard H, et al. The effect of manual therapy knee protocol on osteoarthritic knee pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Can Chiropr Assoc, 2008;52(4):229-42.

- Jackson BD, Wluka AE, Teichtahl AJ, et al. Reviewing knee osteoarthritis – a biomechanical perspective. J Sci Med Sport, 2004;7(3):347-357.

- Mulligan B. Manual Therapy: "NAGS," "SNAGS," "MWMS," Etc., 6th Edition. Wellington, New Zealand: Plane View Services Ltd., 2006: pp. 117-118.

- Li LL, Hu XJ, Di YH, Jiao W. Effectiveness of Maitland and Mulligan mobilization methods for adults with knee osteoarthritis: s systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases, 2022 Jan 21;10(3):954-965.