It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

How Many of Your Patients Have Sarcopenia?

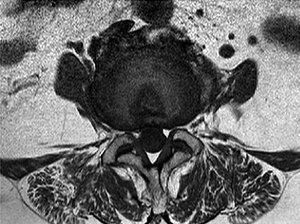

Figure 1 demonstrates the typical appearance of sarcopenia in the paravertebral muscles. Have you considered evaluating your patients for this problem? Sarcopenia is the progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass and function that affects the older population. Most people begin to lose modest amounts of muscle mass after age 30, but the loss of muscle strength increases exponentially with age. Because of decreased muscle strength, problems with mobility, frailty, falls, fractures, decreased activity, diabetes, middle-age weight gain, a loss of physical function and independence results in well over 1.5 million people being institutionalized, with 33 percent admitted because of their inability to perform activities of daily living.

The Scope of the Problem

The ironic fact is that this problem is treatable if recognized and intervention is started early. Over the past two decades, there has been a significant increase in research and interest in sarcopenia. There now is international recognition of a need to identify the condition early for intervention and prevention. Consider these statistics:1

- 65-year-olds will increase from 40 million in 2000 to 55 million by 2020. By 2030, there will be more than 72 million people over the age of 65.

- Sarcopenia affects 30 percent of individuals older than age 60 and more than 50 percent of people older than age 80.

- Approximately 45 percent of the older U.S. population is affected by sarcopenia; 18 million as of 2010.

- Twenty percent of the older U.S. population is functionally disabled.

- A 10 percent reduction in the sarcopenic population would save $1.1 billion. Even though sarcopenia contributes to numerous other health problems and accounts for a similar percentage of health care costs as osteoporosis, no public health campaigns are directly aimed at reducing this disease.

Diagnostic Considerations

Loss of skeletal muscle mass in the elderly is an independent risk factor for falls, disability, postoperative complications and mortality. Although the cause of sarcopenia is not completely understood, it appears to result from a complex bone-muscle interaction in patients with chronic disease and due to aging in general.

Sarcopenia cannot be diagnosed by muscle mass alone. The diagnosis requires two of the following three criteria: low skeletal muscle mass, inadequate muscle strength and inadequate physical performance. The good news is that with early intervention, the process of skeletal muscle deterioration can be arrested and progression slowed.

One of the major problems with sarcopenia is that often, it not noticeable in earlier phases, but becomes more apparent once a critical event such as a fall has occurred or disability has set in. While it is possible to preserve skeletal muscle mass in older age, it is extremely challenging to regain substantial quantities once the loss has occurred. Therefore, a screening strategy for the older population that allows for early detection is extremely important.

Methods for diagnosing loss of muscle mass include dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and bioelectrical impedance analysis. They are relatively inexpensive and accessible, but are generally considered less specific for sarcopenia compared with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Recently, however, due to increasing research in sarcopenia, a tool to quickly evaluate a patient for sarcopenia has been developed. It is a questionnaire known as the SARC-F. (Table 1) The SARC-F includes five components: strength, assistance walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and falls. SARC-F items were selected to reflect health status changes associated with the consequences of sarcopenia.

SARC-F scale scores range from 0 to 10 (i.e. 0-2 points for each component; 0 = best; 10 = worst). A score of 4 or higher represents poor health status associated with loss of strength and performance, while a score of 0-3 represents healthy status associated with relatively normal muscle strength and performance.

It has been determined that these simple questions are as useful as measurements of muscle mass and strength in predicting future functional deterioration, hospitalization and loss of independence.2

| Table 1: Sarc-F Sarcopenia Questionnaire | ||

| Component | Question | Scoring |

| Strength | How much difficulty do you have lifting and carrying 10 pounds? | None = 0 Some = 1 A lot or unable = 2 |

| Assistance in walking | How much difficulty do you have walking across a room? | None = 0 Some = 1 A lot, use aids or unable = 2 |

| Rising from a chair | How much difficulty do you have transferring from a chair or a bed? | None = 0 Some = 1 A lot or unable = 2 |

| Climbing stairs | How much difficulty do you have climbing a fl ight of 10 stairs? | None = 0 Some = 1 A lot or unable = 2 |

| Falls | How many times have you fallen in the past year? | None = 0 1-3 falls = 1 4 or more falls = 2 |

Recommended Treatment

Strengthening exercise and nutritional supplementation are the recommended treatment for sarcopenia.3 Table 2 provides an example treatment protocol recommended by the American Medical Directors Association. However, there are other similar protocols recommended by various organizations and clinical trials. They all include exercise as a core intervention along with supportive nutrition.4-7

Most programs include resistance exercise 2-3 times a week with increasing intensity. All reviews conclude that resistance exercise is an effective intervention for improving strength and physical function in older people. It is better, however, to prevent progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength and function, rather than try to restore it at an older age or when disability has already begun to develop.

Furthermore, the combination of exercise and nutrition is the key intervention to prevent, treat and slow down the progress of sarcopenia. Presently, there are no pharmaceutical agents available to treat sarcopenia. In other words, you just have to get up and work out.

Chiropractors are uniquely positioned to treat this disorder; in fact, many are already treating their patients for sarcopenia, whether or not they are using that particular term for a diagnosis. Make your patients aware of this problem and inform the rest of the health care community that we are the profession best trained to manage this disorder.

Most people wish to remain independent as long as possible. We should remember what Jack LaLanne said: "So many older people, they just sit around all day long and they don't get any exercise. Their muscles atrophy, they lose their strength, their energy and vitality by inactivity." Jack didn't know the term sarcopenia, but he sure knew how to prevent it.

| Table 2: Exercise And Nutritional Interventions For Sarcopenia | |||

| EXERCISE | |||

| Type of Training | Frequency | Intensity | Duration/Set |

| Aerobic exercise | Minimum fi ve days/week for moderate intensity or three days/week for vigorous intensity | Moderate intensity at 5-6 on a 10-point scale; vigorous intensity at 7-8 ona 10-point scale | Accumulate at least 30 min./day of moderate-intensity activity in bouts of at least 10 min. each; continuous vigorous activity for at least 20 min./day |

| Resistance exercise (for major muscle groups using free weights and machines) | At least two days/week | Slow-to-moderate velocity, 60–80% of 1 RM | 8–10 exercises 1–3 sets per exercise 8–12 repetitions 1–3 min. rest |

| Power training (to practice only after the resistance training) | Two days a week | High-repetition velocity, light-to-moderate loading, 30–60% of 1 RM | 1–3 sets; 6–10 repetitions |

| NUTRITIONAL SUPPLEMENTATION | |||

| Intervention | Evidence or Recommendation | ||

| Amount of Protein | Type of Protein | Timing | |

| Protein supplement | At least 1.0–1.2 g/kg/day in people ages 65 years and above GFR 30–60 — 0.8 g/kg/day GFR <30 — between 0.6 and 0.8 g/kg/day | "Fast" proteins are thought to be more benefi cial compared to "slow" proteins but lack robust evidence. | Even distribution of protein intake in main meals through the day |

| Vitamin D | Replace depleted serum vitamin D level and maintain adequate intake at 700 to 1,000 IU/day of cholecalciferol | ||

| Essential amino acid supplementation | Daily leucine 2.5 g or 2.8 g with combination of resistance exercise (benefi ts only shown in a small number of studies) | ||

| Beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbu-tyrate (HMB) | HMB alone or with combination of resistance exercise, or arginine and lysine (evidence not consistently positive and only shown in a small number of studies) | ||

References

- Morley JE, Anker SD, von Haehling S. Prevalence, incidence, and clinical impact of sarcopenia: facts, numbers, and epidemiology - update 2014. J Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 2014;5(4):253-259.

- Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. A simple questionnaire to rapidly diagnose sarcopenia. JAMADA, Aug 2013;14(8):531-2.

- Yu SCY, et al. Clinical screening tools for sarcopenia and its management. Current Gerontology & Geriatrics Research, volume 2016, article ID 5978523.

- Iolascon G, et al. Physical exercise and sarcopenia in older people: position paper of the Italian Society of Orthopaedics and Medicine (OrthoMed). Clin Cases in Mineral and Bone Metab, 2014;11(3):215-221.

- Bauer G, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE study group. J Amer Med Directors Assoc, 2013;14(8):542-559.

- Flakoll P, et al. Effect of ß-hydroxy-ß-methylbutyrate, arginine, and lysine supplementation on strength, functionality, body composition, and protein metabolism in elderly women. Nutrition, 2004;20(5):445-451.

- Stout R, et al. Effect of calcium ß-hydroxy-ß-methylbutyrate (CaHMB) with and without resistance training in men and women 65+yrs: a randomized, double-blind pilot trial. Experimental Gerontology, 2013;48(11):1303-1310.

Author's Note: LaLanne's daily routine in his later years included waking up at 4 a.m. (as he got older, he "slept in" until 5 a.m.); weight lifting / strength training (90 minutes); swimming or running (30 minutes); eating 10 raw vegetables; and eating two meals: a late breakfast and an early dinner.