It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

Think Outside the Box and the Spine (Part 4): The Hips

The prevalence of hip pain is terribly rampant in our modern society. Current statistics indicate that one in four people may develop painful hip arthritis in their lifetime.1 A recent study found that 14.3 percent of participants ages 60 years and older reported significant hip pain on most days in the previous six weeks. Also worth noting is that men reported hip pain less frequently than women.2 And in the 2006 National Health Interview Survey, approximately 30 percent of adults reported experiencing some type of joint pain or stiffness during the preceding month.3

While patients may seek chiropractic because of pain only in one area, the burden lies on us, as chiropractors, to give a thorough evaluation to determine if that pain is a result of a problem somewhere else in the body (e.g., back pain that actually stems from the hips). Joint pain can be caused by osteoarthritis, injury, prolonged abnormal posture, or repetitive motion. The pain can be caused by a condition as simple as a strain all the way to advanced, degenerative changes that necessitate total hip replacement.

The Hips

The hip or acetabulofemoral joint is the joint between the femur and acetabulum of the pelvis. Its primary function is to support the weight of the body in both static and dynamic postures. The hip joints are the most important factors dictating stability and balance.

The hip joint is a synovial joint formed by the articulation of the rounded head of the femur and the cup-like acetabulum of the pelvis. It forms the primary connection between the bones of the lower limb and the axial skeleton of the trunk and pelvis. Both joint surfaces are covered with a strong – but lubricated – layer of hyaline cartilage. The cup-like acetabulum forms at the union of three pelvic bones: the ilium, pubis, and ischium.

The hips are the largest weight-bearing joints in our body, and they have a stable anatomy. The hip joint is a deep socket with a thick joint capsule, strong spiral ligaments, and several powerful, stabilizing muscle groups. The joint itself is not often injured. Most injuries occur secondary to biomechanical imbalances.

Looking Deeper

In practice, we encounter hip pain and dysfunction on a daily basis and in multiple patients. When the average hip-pain patient comes in, they may recount the usual, garden-variety diagnoses they have been given by their physician. Bursitis, tendonitis, arthritis, capsulitis and strained muscles are some of the common afflictions we hear about. The lion's share of blame seems to be leveled against arthritis and degenerative joint disease (DJD).

The concept I teach in all of my seminars and articles is that you should de-emphasize the singular event that brought this patient to your office. In other words, if the patient has just suffered a recent injury to their hip, such as a fall or pain after exercising, don't just focus on that seemingly "traumatic" episode. That's what the allopathic physicians do. They focus on pain and on what "just" happened to the patient that made them come in for crisis care.

That is not to say we should ignore the trauma or incident; note it, but then delve deeper. When you are assessing any type of lower-body problem, don't forget the relationship to the feet, ankles and knees! Not only is it significant, but identifying the underlying cause of why your patient became susceptible to being injured also becomes your answer to how to stabilize and protect them in the future.

Lower-Body Misalignment

In each of the previous three articles in this series, I outlined a sequential bone-and-joint misalignment pattern that originates from the lack of the three-arch support in our feet. This failure of the feet to adequately and correctly support the weight-bearing stress of our body and disperse ground forces during weight-bearing can have negative effects on the body.

In my experience, I have found that more than 80 percent of the time, this failure of arch support results in a flattening or overpronation of the feet. Excessive foot pronation will cause biomechanical imbalances and stresses that manifest as pain somewhere in the body.

Recall that when the feet are excessively pronated, the tibia and femur bones internally (medially) rotate. This creates a torsional pressure on the femur shaft and into the head as it articulates with the acetabulum. Internal rotation of the femur head also adducts the shaft of the femur, creating forces that shape how the femur head will misalign.

A great way to get your patients to understand this is to do the following demonstration with them. First, stand up. Take your hands and place them on both greater trochanters. Now forcefully drop your arches down to the floor as far as you can and you will be re-creating or accentuating dropped or flattened arches seen in excessive foot pronation. Close your eyes and feel what is happening to your body. You can follow the stress from your feet, ankles, knees to the hips. Focus on your hips.

Think about what you are feeling at the hips during this exercise; you can actually feel the internal rotation at the femur head, as well as the flexion of the hip. Since many patients we see deal with chronic, long-standing and often undetected, excessive foot pronation, their hips have been under this stress for months to years. When a joint is misaligned or subluxated for long periods of time, the body goes through compensatory changes. The iliopsoas, tensor fascia lata, gluteus medius/maximus, piriformis muscles and the iliotibial band (ITB) become chronically hypertonic and weaker.

This is not to say the patient could not have more serious problems in the hip area. Do the standard orthopedic tests to cover all bases. Obtaining an X-ray series on the hips may yield substantial information, especially when arthritis is suspected. This is your call depending on your patient presentation and how you feel it may change your treatment protocols. Arthritis or DJD of the hips that is moderate to severe will definitely affect how your adjustments hold and how much conservative care the patient can actually benefit from until surgery needs to be considered.

Adjustments We Can Perform on the Hip

Internally (medially) rotated femur: With the patient supine, lock the tibia between your knees and grasp the middle to distal femur with both hands. With an internal to external, long axis line of drive, gently twist the femur outward. There is no heavy-handed or violent thrusting with this maneuver. It's more like a gentle, directional mobilization of the shaft of the femur externally. (Image 1a)

Another option is to cup the heel with one hand and the dorsum of the foot with the other with the patient supine. Rotate the entire thigh / leg into external rotation and then traction down the long axis of the shafts of the bones. Add an appropriate thrust at end range. This decompresses the hip joint and cavitation is often heard. (Image 1b)

Lateral femur head: The patient should be side-lying with the involved hip up. You can lift the leg with the inferior hand and place the palm of the superior hand on the greater trochanter of the femur. The adjustment occurs by thrusting from lateral to medial, slightly superior to inferior. For doctor comfort, the addition of a drop table piece or spring-loaded instrument helps tremendously. (Image 2)

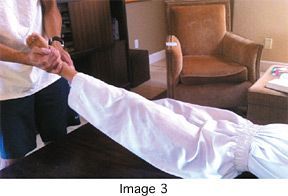

Anterior femur head: Patient is supine with the knee bent comfortably to relax the illiopsoas muscle. Take knife-edge contact onto the anterior femur head near the inguinal region and thrust anterior to posterior. You may add slight inferiority as well. Again, use of a drop table or spring-loaded instrument here is extremely effective. (Image 3)

Remember that for any of the adjustments described above, there are variations that we do not have the space to discuss in this article. Because we understand the patterns that exist most of the time, we can allow for a random posterior femur head here and there. Just trust your instincts and fix what you find.

Don't forget that by the time you get to adjusting the hips, you likely have already adjusted the feet, ankles and knees. All of these areas are important. (If you need a review, look at the first three articles in this series.)

Stabilizing the Joint

Once the adjustments have been made, you have to think about how to stabilize the joint. Here are some tools to utilize and ideas to consider:

- Elastic tape (functional or sports taping)

- Trochanter belt

- Custom foot orthotics. This will address the arches of the foot and help to stabilize the body.

- Appropriate shoe types. What patients wear affects their body, not just their feet and should be evaluated.

- Modifying activities. What the patient's doing may not be working anymore and should be addressed to avoid further injury.

I hope that by this point, the message is clear: Although we should never overlook the importance of a traumatic or acute-onset injury / pain, many patients come to us with chronic pain and dysfunction. Take a step back, think globally and try to draw some connections between what the patient is feeling and the biomechanical patterns that exist from the feet upward. This may provide substantial insight into not only the problem, but also how to provide comprehensive conservative care.

References

- Murphy LB, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, et al. One in four people may develop symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in his or her lifetime. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2010;18(11):1372-9.

- Christmas C, Crespo CJ, Franckowiak SC, et al How common is hip pain among older adults? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Fam Pract, 2002 Apr;51(4):345-8.

- National Health Interview Survey, 2006. Public-use data file. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm.

This is the fourth in a series of six articles dedicated to the extremities, covering clinical discussions from the feet to the ankles, knees, hips, hands / wrists and elbows to the shoulders. Part 1 appeared in the Feb. 12, 2012 issue; part 2 ran in the April 22 issue; and part 3 appeared in the July 1 issue.