It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

Early Mile-High Chiropractic

Denver, the Mile-High City, has long been a center for chiropractic activities.4 In recent memory, it was the site of the short-lived Colorado College of Chiropractic, a division of Marycrest University, which was led by Doug Davison, DC. However, Denver's chiropractic tradition dates back to the early years of the profession. Among the best-known names associated with chiropractic and Denver are: Homer G. Beatty, DC, ND; Senator Neal Bishop, DC; Willard Carver, LLB, DC; A. Earl Homewood, DC, ND; Frank Margetts, DD, LLB, DC; Leo Spears, DC; Leo Wunsch, II, DC; and the National Chiropractic Association (NCA). I will touch briefly on these various people and organizations.

| |

|

|

| |

| |

Perhaps the best recognized name on our list is that of Leo Spears, DC (1894-1956), a 1921 alumnus of the Palmer School of Chiropractic (PSC). Dr. Spears was an extremely litigious individual who battled with local and state medical authorities for decades in his effort to promote chiropractic and build his hospital, which was undoubtedly the largest inpatient facility in the profession's history.12,13 The Chiropractic Research Foundation, forerunner of today's Foundation for Chiropractic Education & Research (FCER), briefly flirted with Dr. Spears in an effort to secure the Denver facility as a research center.10,14 However, these efforts were not successful, owing largely to Spears' reluctance to give up control of the institution.11 Following his death in the mid-1950s, his nephews, Dan and Howard Spears, also chiropractors, carried on their uncle's work.

|

|

Leo Spears arrived in Denver at about the same time as attorney-chiropractor-minister Frank Margetts (1871-1968). Dr. Margetts graduated from the National College of Chiropractic (NCC) in 1920 and taught at his chiropractic alma mater for a few years while his wife completed her chiropractic education.12 She graduated in 1922, and the couple relocated to Denver, where Frank was promptly elected president of the Colorado Chiropractic Association. He served no more than a year, for he was elected president of the American Chiropractic Association (ACA) in 1923, and in this capacity, made his most significant contributions to the profession.6 Margetts led the opposition both to political medicine's anti-chiropractic campaigns and to B.J. Palmer's neurocalometer-centered "back-to-the-back" program in the mid-1920s. He spoke in state legislative halls around the nation on behalf of the ACA's quest for chiropractic licensing laws, and resigned the presidency when it seemed the most expeditious way to bring about a merger of the ACA with the formerly Palmer-led Universal Chiropractors' Association. That amalgamation took place late in 1930 and gave birth to the NCA, the immediate predecessor of today's ACA.7

|

|

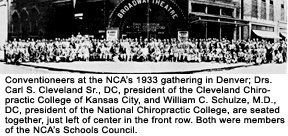

Denver served as the site for the NCA's 1933 convention, which drew chiropractors and their leaders from around the nation. The NCA's push to raise educational standards in the profession had not yet begun in earnest at this point, and the organization was focused primarily on contending with the spread of basic science legislation. Popular as a means of generating publicity for the still embryonic profession were the NCA's "Perfect Back" contests (destined to be reincarnated as the "Posture Queen" competitions of the 1950s).

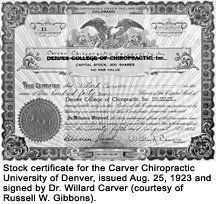

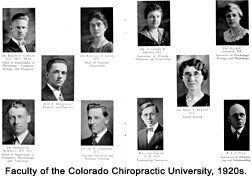

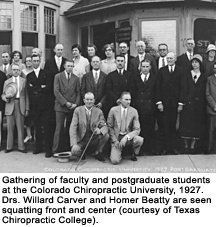

Denver was the location for one of the several chiropractic colleges founded by attorney-chiropractor Willard Carver. The first and largest of the Carver schools was located in Oklahoma City.5 Carver's Denver institution was variously known as the Denver College of Chiropractic, Carver Chiropractic University, Colorado Chiropractic University and the University of Natural Healing Arts (UNHA). Dr. Carver presided over the institution at its inception, but turned the reins over to his nephew, Homer G. Beatty, DC, ND. The latter disappointed his uncle by introducing what Carver considered "mixing" methods of healing, and by removing the word chiropractic from the title of the institution.2 The future president of the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College, A. Earl Homewood, DPT, DC, ND, LLB, earned the first of his several doctorates from the UNHA - the Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) - prior to his training at the Western States College.7 The UNHA closed its doors in 1962, but the college corporation has continued to function. Its main activity is awarding scholarships to chiropractic students.4

The Carver school was but one of several institutions which have provided training for chiropractors in the Mile-High City (see Table 1).

|

|

| |

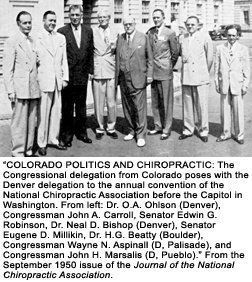

Colorado passed its first chiropractic statute in 1933,4 due in large measure to the efforts of state representative (later state senator) and Denver practitioner Neal Bishop, DC, who also served as a faculty member and vice president of the UNHA.1 Bishop was also influential in establishing a continuing education requirement for the re-licensure of chiropractors in the state.4 Dr. Bishop's career and contributions to the profession have yet to be told in any depth.

| TABLE 1 |

Several chiropractic educational institutions were located in Denver (courtesy of Glenda Wiese, PhD, and Louis O. Gearhart, DC):

|

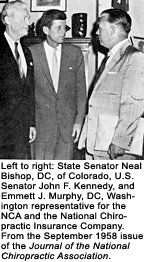

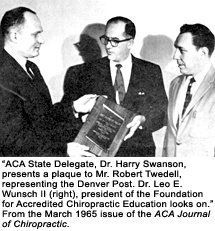

Denver native Leo Wunsch, II, DC (1924-1996), practiced immediately following his 1952 graduation from Lincoln Chiropractic College until his retirement. The son of a PSC alumnus, Leo II followed his father's lead and became a chiropractic radiologist. He served on the governing boards of several chiropractic organizations,3 including the state Board of Chiropractic Examiners, the FCER (over which he presided from 1964-1969), and perhaps most notably, the National Chiropractic Mutual Insurance Company (NCMIC) during 1962-1981, including two nonconsecutive two-year terms as president of the company.9

There are many more stories to be mentioned about chiropractic in the Mile-High City. Perhaps another time.

References

- Budden WA. An analysis of recent chiropractic history and its meaning. Journal of the National Chiropractic Association, June 1951;21(6):9-10.

- Carver W. History of Chiropractic, unpublished. Oklahoma City: the author, circa 1936 (Archives of Palmer College of Chiropractic West).

- Dzaman F, et al. (eds.) Who's Who in Chiropractic, International, 2nd Edition. Littleton CO: Who's Who in Chiropractic International Publishing Co., 1980.

- Gearhart LO. Letter to J.C. Keating, Jan. 9, 1998.

- Jackson RB. Willard Carver, LLB, DC, 1866-1943: doctor, lawyer, Indian chief, prisoner and more. Chiropractic History, December 1994;14(2):12-20.

- Keating JC. The short life and enduring influence of the American Chiropractic Association, 1922-1930. Chiropractic History, June 1996;16(1):50-64.

- Keating JC. The Homewood influence in Canada and beyond. Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, March 2006a;50(1):51-89.

- Keating JC. The gestation and difficult birth of the American Chiropractic Association. Chiropractic History, 2006b (Winter):26(2):91-126.

- Keating JC, Sportelli L, Siordia L. We Take Care of Our Own: NCMIC and the Story of Malpractice Insurance in Chiropractic. Clive IA: NCMIC Group Inc., 2004.

- Logic FO. An open letter to the chiropractors of America. National Chiropractic Journal, October 1947;17(10):8-9.

- Logic FO. A statement about Spears Sanitarium. National Chiropractic Journal, October 1948;18(10):15.

- Rehm WS. Who Was Who in Chiropractic: A Necrology. In: Dzaman F, et al. (eds.) Who's Who in Chiropractic, International, 2nd edition. Littleton CO: Who's Who in Chiropractic International Publishing Co., 1980.

- Rehm WS. Prairie Thunder: Dr. Leo L. Spears and His Hospital. Davenport IA: Association for the History of Chiropractic, 2001.

- Rogers LM. Editorial. National Chiropractic Journal, September 1947;17(9):6.