It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

Pre-Stress Test for Motion Palpation

This article is one of the most significant concepts I have ever written about for Dynamic Chiropractic. Ever since I attended courses by Dr. Len Faye on motion palpation (MP) years ago, I have used MP as a principal method of discovering which vertebral segment requires treatment. Usually we pick out a tender, restricted segment, but how do we really know that adjusting this particular segment will relieve the patient's pain? Could it be that the most fixated segment is not necessarily the major segment to treat? The segment that should be adjusted should be the one that greatly relieves or eliminates the pain the patient expresses on a painful, limited motion. The direction of the thrust should be in the direction that relieves or eliminates the pain.

Recently, I discovered a technique used by Mulligan,1 in which he pre-stresses vertebral segments to determine which particular segment he wants to mobilize. Most of his teachings deal with a mobilization-type technique rather than a high-velocity, low-amplitude adjustment/manipulation.

For the past four months, I have used a pre-stress routine based on the Mulligan concept that allows me to predetermine if the vertebral segment I intend to adjust will relieve the patient. I have used this routine for all spinal segments, from the atlas to the sacrum and iliac joints. For example, a patient states that on bending forward in the standing or sitting position, there is pain in the vicinity of the lumbar spine. Let us say that in standing, as the patient bends the first 30°, he or she points to the L2 or L3 area. Typically, in forward bending the upper lumbar segments move first. We know that in forward bending, the superior facet must move forward on the inferior facet. Early pain on lumbar flexion is usually due to an upper lumbar segment and pain near the end of flexion 70° to 90° may refer to pain at a lower spinal segment, but in reality, any lumbar or sacral segment might be causative.

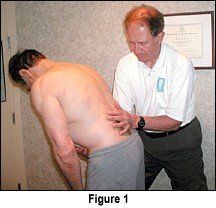

The procedure is as follows: The patient complains of pain on forward flexion in the lumbosacral area at 75° of flexion. You can assume that the superior facets of one of the lower lumbar segments are not moving forward and therefore cause pain on lumbar flexion. "Pre-stressing" refers to taking a contact beneath the spinous process (affecting both facets) or the articular pillar on either side (affecting more a unilateral facet), and putting pressure on these contacts in the direction of the facet angle in order to passively move the superior facet on the inferior facet. Hold this contact in the direction of the facet alignment, using enough pressure to influence some movement of the facet as the patient flexes forward (Figure 1). With your other hand, hold them around the ASIS to create stabilization. If this contact greatly relieves or eliminates the pain of forward bending, that is the segment you want to treat. If the pressured contact aggravates or doesn't relieve the flexion pain, go to a segment above or below. Sometimes there is great relief, but if you push the spinous in a right or left direction and also push anterior superior while the patient bends forward, you might completely relieve the pain. Ideally, you want to stress this vertebra in a direction that eliminates the pain. My motto is "no pain equals gain," and every adjustment we ever deliver should be in the direction of "no pain." If the patient complains of lumbar pain only in the sitting position, the pre-stress method is used in the sitting position.

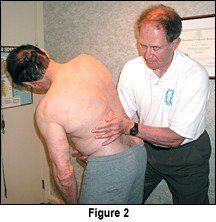

If there is pain on lateral lumbar bending (Figure 2), taking a contact on the side of lumbar pain over the articular pillar and moving the facet anterior superior (for the lumbar facets) while the patient laterally bends will relieve or greatly eliminate the pain of lateral bending, if you are on the correct segment. You might have to contact each side to find the particular facet that is causing the lateral bending pain. That is the segment which should be adjusted in the direction of relief. The proof is in post-stressing immediately after the adjustment, when the patient is asked to bend again, either in flexion or side-bending, depending on the painful direction.

Recently a patient complained of right buttock pain on forward flexion. Attempts to move the superior facets superiorly from the sacrum to T12 did not relieve the patient's pain. I assumed that the spine was not involved. I evaluated the hip external rotators where the buttock pain presented itself, and found a restriction in the piriformis area. The use of post-isometric relaxation to the involved external rotators allowed the patient to bend forward without buttock pain, suggesting this pre-stress method can be used to eliminate the spine as a source of pain.

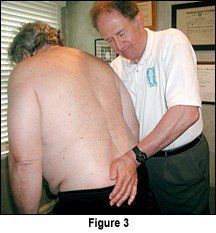

Another patient complained of sacral pain and pain radiating down the back of the thigh on forward flexion. Pushing down inferiorly on the sacrum (Figure 3) relieved the buttock and thigh pain. Adjusting the sacrum inferiorly allowed immediate painless forward flexion.

If there is pain in lumbar extension, pre-stressing the segment superiorly prevents the facet from maintaining its inferior position and also will relieve or eliminate the pain.

This pre-stress routine works for all limited, painful ranges of spinal motion and allows the practitioner to determine exactly the direction that must be adjusted to relieve the pain. Immediately after the adjustment, there should be a greatly or totally reduced level of pain due to the aggravating motion. Hopefully this procedure will be taught by all of our colleges and groups interested in motion palpation.

Reference

- Mulligan BR. Manual Therapy: Nags, Snags, Mwms, etc., 5th ed. Wellington, New Zealand; Plane View Services Ltd., 22 Westview Grove, 2005.