It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

A Case of Transient Osteoporosis

Transient osteoporosis of the hip (TOH) is considered a relatively rare disorder that affects women in their third trimester of pregnancy and middle-age men. Curiously, it has a predilection for the left hip. In general, it is most common in men in their third or fourth decade of life. The etiology is unknown and it is considered self-limiting. The clinical presentation is generally acute onset of hip and groin pain with no history of trauma. The hip pain is progressive and exacerbated by weight-bearing; it is associated with decreased range of motion and a limp. The pain generally resolves over a period of six to 10 months following initial onset.

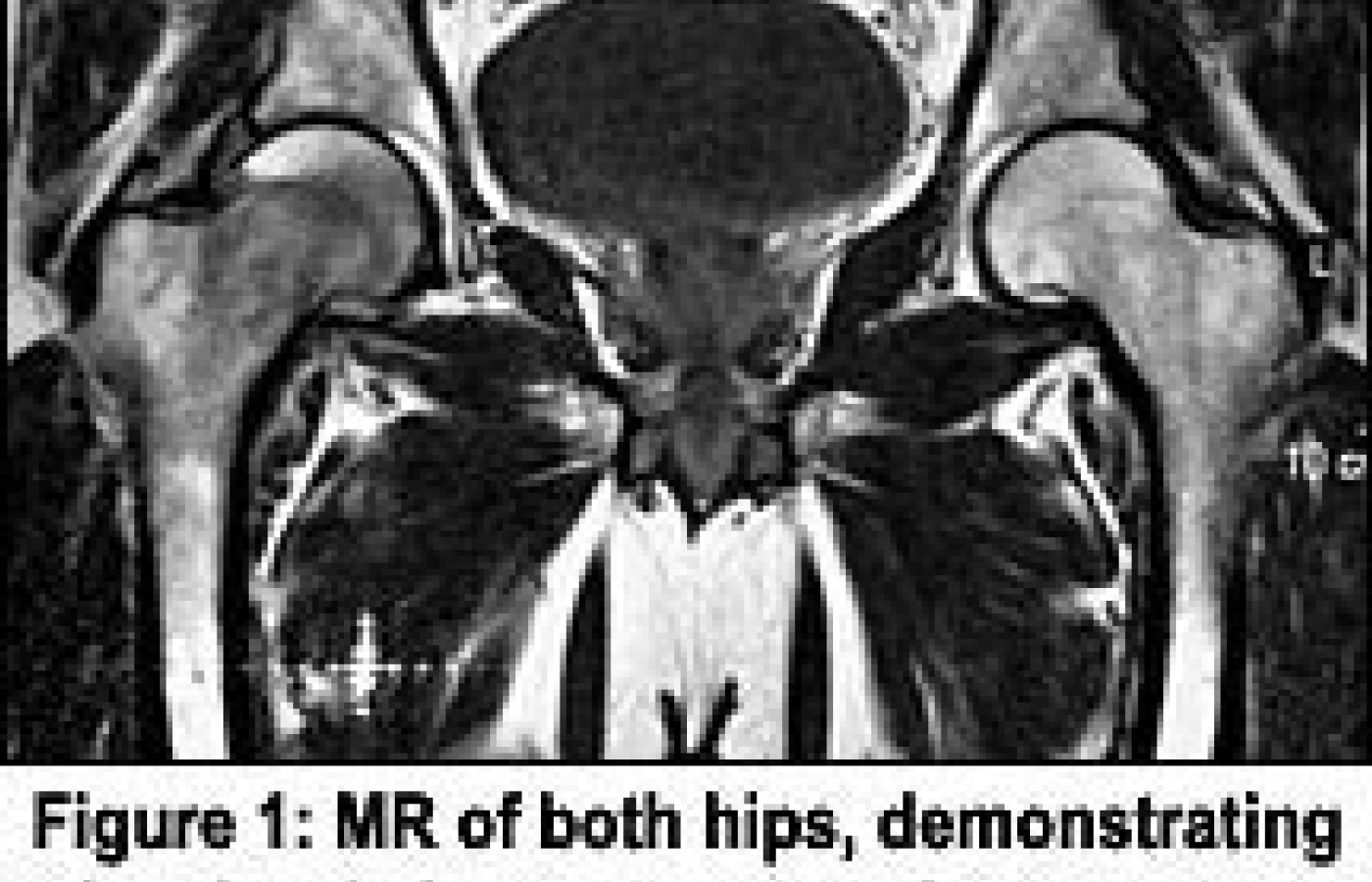

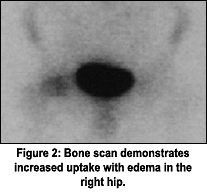

With a clinical presentation such as this, we generally need to be concerned with avascular necrosis (AVN), an inflammatory arthritis and an infection. There are other disorders that will give similar presentations, such as regional migratory osteoporosis and transient bone marrow edema syndrome (TBMES) - I would venture a guess that we may find these are just different forms of transient osteoporosis. For that matter, I prefer to describe transient osteoporosis as transient bone marrow edema, because the MR findings in both are essentially the same: hyperintense marrow signal in the femoral head and neck on the T2-weighted images.

The major problem in confirming the diagnosis is differentiating TOH from AVN. With AVN in the hip, there is generally a history of trauma, but that doesn't rule out other causes, such as steroid-induced AVN. We all know middle-age males are not always the best historians; for that matter, most patients are not good historians. How many times has a patient given you some very pertinent information weeks later, that they didn't remember at their initial visit; or perhaps something you say to them jogs their memory. Regardless, your dilemma is making the best diagnosis with the information available to you.

MRI is the most sensitive, noninvasive method for diagnosis of both TOH and AVN. Diagnosis involves detection of marrow foci of decreased signal on T1-weighted images and the characteristic double-line sign. The double-line sign is the differentiating sign for AVN. With TOH, there is diffuse marrow edema that is hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2. The double-line sign is seen on the conventional T2 sequences; the inner border of the peripheral band shows high signal in 80 percent of cases. This is called the double-line sign of avascular necrosis, and is considered to be pathognomonic of AVN. Various reports state that the inner "bright" signal is due to the reactive interface, or granulation tissue, between infarcted and normal marrow. Other authors have shown that by changing the phase and frequency direction, the position of the inner bright signal changes in some cases, such that the etiology is that of a chemical shift artifact. Regardless of the etiology in specific cases, recognition of the double-line sign is useful, since it is frequently characteristic of AVN.1-5

| Table 1: Ficat and Arlet Staging of AVN Stage Findings

|

| Table 2: MRI staging of AVN3 | ||||

| Class | T1 | T2 | Definition | |

| A | bright | intermediate | "fat" signal | |

| B | bright | bright | "blood" signal | |

| C | intermediate | bright | "fluid" or "edema" signal | |

| D | dark | dark | "fibrosis" signal | |

The problem arises when the double-line sign is not present. There can be a low signal in the femoral head on T1 with a high signal on T2, consistent with a bone marrow edema pattern, without the dark band of AVN on T1 sequences. This MR finding would lead us to the diagnosis of TOH, which is self-limiting, but actually could be a very early development of AVN that needs intervention. The problem with not having the correct diagnosis is the treatment. The general treatment for TOH is conservative, with serial MR to document resolution. On rare occasions, a core decompression is performed, which may produce a rapid decrease in pain and shorten the resolution time. The treatment for AVN is core decompression (with or without bone grafts), osteotomy and electrical stimulation. Best results using core decompression are achieved when there is a grade I or II AVN, before there is any collapse of the femoral head.

Do you remember the stages of AVN? There are two staging classifications of AVN - one based on radiographs (Table 1)5 and the other based on MR signal intensities (Table 2).3 The accuracy of radiographic staging may be improved using CT to detect a subchondral lucency, indicating advanced, or stage III disease. Note, however, that CT does not depict the earliest marrow abnormalities resulting in osteonecrosis.6-8

MR staging of AVN is based on the signal intensity of the center of the marrow inside the dark line of necrosis (Table 2). Radiographically occult AVN will generally be depicted on MRI as any of classes A to C. The MR classification implies that the infarcted bone progresses in an orderly manner through the various classes. However, this is not necessarily the case, since frequently, several "classes" of signal intensity are present within the infarcted marrow. Furthermore, unlike radiographic staging, MR classes have little predictive value regarding the prognosis for collapse of the femoral head. However, the MRI size and position of the AVN lesion are related to prognosis. The prognosis is best when less than 25 percent of the weight-bearing surface of the femoral head is involved.

Occasionally, AVN may manifest as a diffuse area of decreased signal on T1-weighted images and increased signal on T2-weighted images involving the femoral head, neck, and occasionally, the intertrochanteric femur. This has been termed the "bone marrow edema" pattern on MR imaging, since the signal intensities are compatible with increased free-water content. This is the classic pattern attributed to transient osteoporosis and TBMES. If the lesion is truly an AVN, it will change in its appearance with follow-up studies, demonstrating the bone marrow edema pattern evolving into focal patterns entirely characteristic of AVN.

The MR pattern of bone marrow edema is not specific. The differential diagnosis includes AVN, transient osteoporosis, bone bruise, infiltrative disease, and transient bone marrow edema syndrome. Although the clinical history can be helpful in distinguishing between these entities (e.g., a history of trauma as the etiology of a bone bruise), in other cases, a definite diagnosis can only be made based on the time course of the imaging and clinical findings.

When attempting to differentiate these entities, the MR may only demonstrate the bone marrow edema, which may be indicative of transient osteoporosis of the hip and transient bone marrow edema syndrome. I think both may be of a similar etiology, and the treatment is in general the same; both are self-limiting. AVN and septic arthritis are not similar and require different treatment. Aspirating the joint should differentiate the septic joint from AVN, but follow-up studies will need to be done to differentiate AVN from TOH or TBMES. The treatment is very different. One should consider AVN as the primary diagnosis unless proved otherwise.

References

- Hungerford DS, Zizic TM. Pathogenesis of ischemic necrosis of the femoral head. Hip 1983:249-262.

- Hopson CN, Siverhus SW. Ischemic necrosis of the femoral head: treatment by core decompression. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1988;70A:1048-1051.

- Mitchell DG, Rao VM, Dalinka MK, et al. Femoral head avascular necrosis: correlation of MR imaging, radiographic staging, radionuclide imaging, and clinical findings. Radiology 1987;162:709-15.

- Turner DA, Templeton AC, Selzer PM, Rosenberg AG, Petasnick JP. Femoral capital osteonecrosis: MR finding of diffuse marrow abnormalities without focal lesions. Radiology 1989;171:135-40.

- Ficat RP, Arlet J. Necrosis of the Femoral Head. In: D. S. Hungerford, ed. Ischemia and Necross of Bone. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1980: 171-182.

- Lafforgue P, Dahan E, Chagnaud C, Schiano A, Kasbarian M, Acquaviva PC. Early-stage avascular necrosis of the femoral head: MR imaging for prognosis in 31 cases with at least 2 years of follow-up. Radiology 1993;187:199-204.

- Bluemke DA, Petri M, Zerhouni EA. Femoral head perfusion and composition: MRI and MRS evaluation in patients at risk for avascular necrosis. Radiology 1995;197:433-438.

- Hayes CW, Conway WF, Daniel WW. MR imaging of bone marrow edema pattern: transient osteoporosis, transient bone marrow edema syndrome or osteonecrosis. Radiographics 1993;13:1001-1011.

Recommended References for Further Reading

- Jones JP Jr. Intravascular coagulation and osteonecrosis. Clin Orthop 1992;277: 41-53.

- Van Veldhuizen PJ, Neff J, Murphey MD et al. Decreased fibrinolytic potential in patients with idiopathic avascular necrosis and transient osteoporosis of the hip. Am J Hematol 1993;44: 243-248.

- Nishino M, Matsumoto T, Fujii H, et al. Hemodynamic study in the Femoral Head at Risk for Osteonecrosis and Bone Marrow Edema Syndrome. ARCO96 Fukuoka abstract, page 44.

- Staudenhertz A, Leitha T, Breitenseher MJ, et al. Pattern Recognition in the Scintigraphic Differential Diagnosis of AVN, BME and Other Disorders of the Hip. ARCO95 Vienna abstract, page 24.

- Kubo T, Hirasawa Y, Yamamoto T, et al. The Morphological Studies of Transient Osteoporosis of the Hip. ARCO96 Fukuoka abstract, page 43.

- Glueck CJ, Freiberg R, Glueck HI et al. Hypofibrinolysis: a common, major cause of osteonecrosis. Am J Hematol 1994;45:156-166.

- Jones JP Jr. Concepts of etiology and early pathogenesis of osteonecrosis, Schafter IM (ed): Instructional Course Lectures. Chicago, IL. Amer Acad Orthop Surg 1994;43:499-512.

- Jones JP Jr. Osteonecrosis, Koopman WJ (ed). Arthritis and Allied Conditions: A Textbook Of Rheumatology, 13th edition, Baltimore, MA, Williams and Wilkins. 1996, pp1677-1696.

Deborah Pate, DC, DACBR

San Diego, California

patedacbr@cox.net