It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

Prevent and Even Reverse Bunion Formation - Without Surgery

- There is a growing body of evidence that shows you can prevent and even reverse mild to moderate cases of HAV with conservative interventions.

- Perhaps the most promising conservative care for the treatment and prevention of HAV is the prescription of foot- and leg-strengthening exercises.

- Unlike many medical interventions, there are no dangerous side effects to strengthening your toes.

Even though the word bunion is widely used to describe the condition in which the big toe angles out while the first metatarsal angles in, the technical name for this condition is either hallux abductus or hallux abductovalgus (HAV), depending upon whether the great toe is rotated in the frontal plane.

Bunion, which comes from the Latin word for “enlargement,” actually refers to the combination of a thickened callus, a swollen bursa, and the bony prominence that forms on the inner side of the first metatarsal head. The bursa is especially painful while wearing tight-fitting shoes, as it gets trapped between the skin and the enlarged metatarsal head.

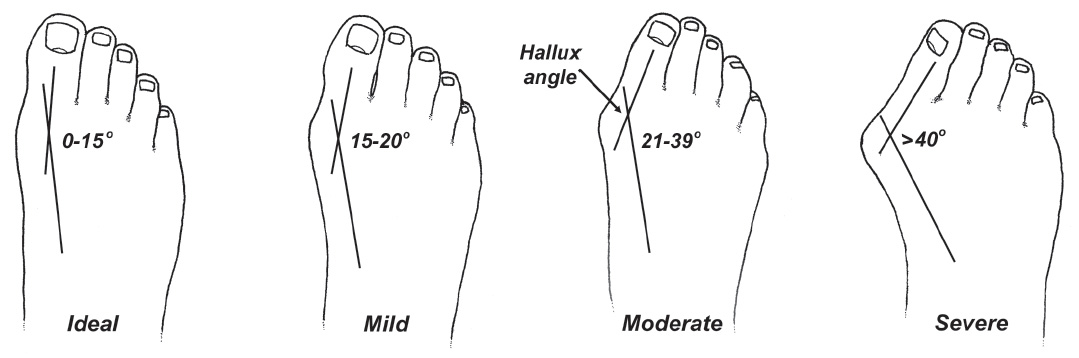

The Manchester grading scale allows you to classify the severity of HAV by visually evaluating alignment of the first metatarsal and the big toe. (Fig. 1) While mild HAV rarely causes problems, moderate and severe cases of HAV can compromise the stability of the entire foot, causing pain, poor physical performance, gait disturbances, and impaired balance.1

HAV is surprisingly common. In a recent study of almost 500,000 people, Nix, et al.2 found that 8% of teenagers, 23% of adults, and 36% of people over the age of 65 suffer with this often-painful condition. The authors of this study note that women are 2.3 times more likely to develop HAV, which many authors attribute to the regular use of poor-fitting shoes.

While some experts question the connection between poor-fitting shoes and the development of HAV,3 a larger number of studies suggest there is a strong connection.4-6

While surgical reconstruction is often considered the only way to alter the bony alignment and reduce the degree of HAV, there is a growing body of evidence that shows you can prevent and even reverse mild to moderate cases of HAV with conservative interventions. Perhaps the most promising conservative care for the treatment and prevention of HAV is the prescription of foot- and leg-strengthening exercises.

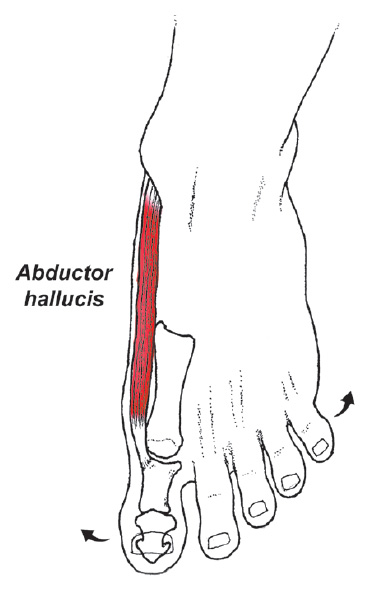

In 2015, researchers from Korea divided 24 people with HAV into two groups: one group received orthotics only, and the other group wore orthotics and performed a simple toe spread-out exercise 20 minutes per day, four days a week for eight weeks.7 (Fig. 2) At the end of the study, the individuals wearing orthotics and performing the toe exercises had a 3.4 degree decrease in their hallux angle along with a 24% increase in the volume of their abductor hallucis muscle.

In contrast, individuals wearing orthotics only had no change in their hallux angle and had a slight reduction in the volume of their abductor hallucis muscle.

In what has to be the most detailed study to date on the effect of conservative care on HAV formation, a researcher from Cairo8 performed a variety of interventions, including various manual therapies, foot-strengthening exercises, calf stretches, and the routine use of silicone toe separators to determine the effect these interventions would have on pain, function, and the radiographically measured hallux angle.

The author took 56 women with moderate HAV and divided them into a control and a treatment group. The control group took anti-inflammatory medications and performed normal activities. The treatment group received 36 sessions in which joints of the foot and ankle were mobilized and calf stretches were performed to increase ankle range of motion. The treatment group also received a series of foot-strengthening exercises and were asked to wear silicone toe separators for a minimum of eight hours per day.

At the end of this 12-week study, the hallux angle in the treatment group changed markedly, decreasing from 32 degrees to 23.8 degrees. In contrast, the control group had no change in their angle. The treatment group also had significant increases in their ankle range of motion (increasing from 9.5 degrees to 15.2 degrees) and their toe strength (which increased approximately 30%).

Even better, individuals in the treatment program maintained the majority of these improvements one year later. Importantly, there were also significant improvements in pain and function in the treatment group.

The thing I like most about this study is that as good as the outcomes were, they could have been much better. For example, while the treatment group received excellent manual therapy in which joints of the forefoot, midfoot and ankle were mobilized, the author failed to measure and/or specifically attempt to increase motion in the first MTP joint.

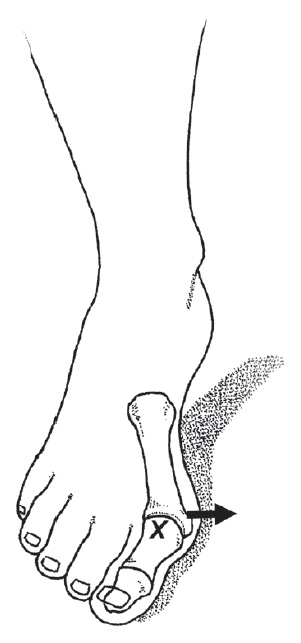

According to Clough,3 limited first MTP dorsiflexion is a primary cause of chronicity with HAV, as upon reaching the limited end range of motion, the base of the hallux drives the first metatarsal farther into adduction. (Fig. 3) Clough claims that restoring first MTP dorsiflexion is one of the most important things you can do to prevent progression of HAV.3

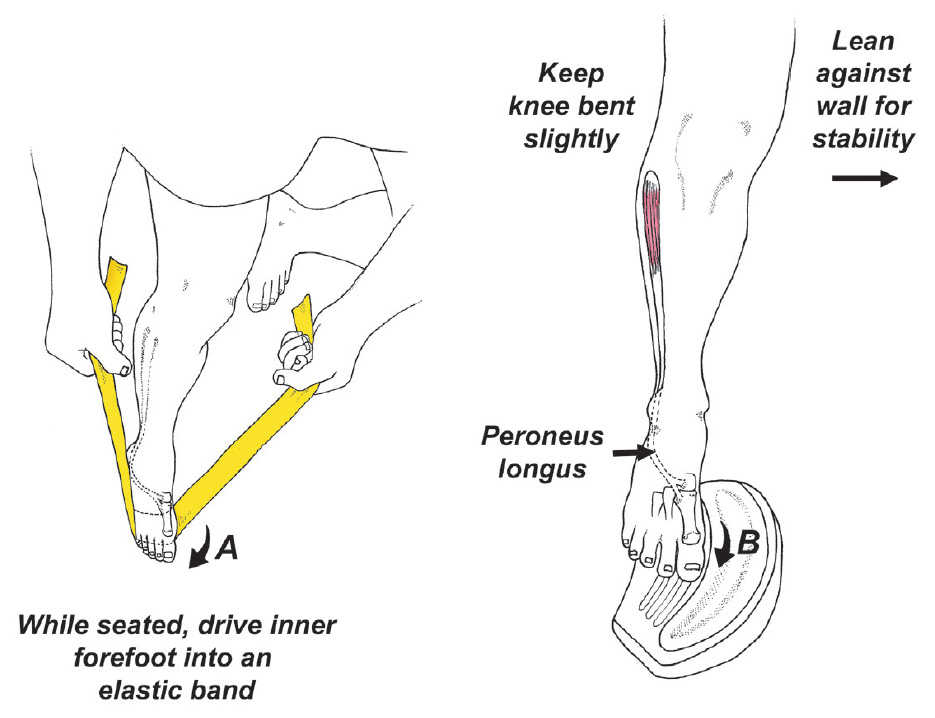

Perhaps the biggest shortcoming in the Abdalbary study8 was that the author failed to include exercises to strengthen peroneus longus. This oversight is significant because peroneus longus is the body’s most powerful stabilizer of the first metatarsal.9

In a detailed analysis of muscle function associated with the development of HAV, researchers from Switzerland proved that peroneus longus is far and away the most important stabilizer of the first metatarsal because of its powerful attachments to the base of the first metatarsal and medial cuneiform.9 The authors stated that because the ability of a muscle to generate force is dependent upon its cross-sectional area and its overall length, the peroneus longus is the ideal muscle for stabilizing the inner forefoot.

Clinically, it is easy to measure peroneus longus strength by placing a toe-strength dynamometer beneath the first metatarsal head and noting resistance. Ideally, you should generate at least 10% of body weight when performing this test. Although there are multiple ways to strengthen the peroneus longus, my two favorite exercises are illustrated in Figure 4.

Based on the latest research, aggressive strengthening of the abductor hallucis and peroneus longus muscles can play an important role in not just treating, but also preventing the formation of bunions. Additional research shows that wearing toe separators at night can reduce the size of a bunion by as much as 4 degrees,10 and chiropractic manipulation to restore first metatarsal dorsiflexion should be considered in people with limited MTP motion. Of course, appropriate shoe gear should be recommended, and the routine use of high-heel shoes should be discouraged.

While surgical correction is often necessary for complex cases, the majority of people with mild to moderate degrees of HAV respond well to these conservative interventions. Ideally, these exercises should be initiated early in life, as research shows that weakness of the abductor hallucis begins decades before the development of HAV,11 and unlike many medical interventions, there are no dangerous side effects to strengthening your toes.

References

- Menz H, Morris M, Lord S. Foot and ankle characteristics associated with impaired balance and functional ability in older people. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci, 2005;60:1546-1552.

- Nix S, Smith M, Vicenzino B. Prevalence of hallux valgus in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Research, 2010 Dec;3:1-9.

- Clough J. Position of the first metatarsophalangeal joint and the effect on hallux abductovalgus deformity progression and reversal. J Int Foot & Ankle Foundation, 2022 Feb 17;1(2).

- Wyderka M, Gronowska T, Szeląg E: The crooked foot and the quality of life. Polish Nursing, 2013;49:169-75.

- Puszczałowska-Lizis E, Dabrowiecki D, Jandziás S, Zak M. Foot deformities in women are associated with wearing high-heeled shoes. Med Sci Monitor: Int J Exper Clin Res, 2019;25:7746.

- Dufour A, Broe K, Nguyen U, et al. Foot pain: is current or past shoe wear a factor? Arth Rheum, 2009;61:1352-1358.

- Kim M, Yi C, Weon J, et al. Effect of toe-spread-out exercise on hallux valgus angle and cross-sectional area of abductor hallucis muscle in subjects with hallux valgus. J Phys Ther Sci, 2015;27(4):1019-22.

- Abdalbary SA. Foot mobilization and exercise program combined with toe separator improves outcomes in women with moderate hallux valgus at 1-year follow-up: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Podiatric Med Assoc, 2018 Nov 1;108(6):478-86.

- Dygut J, Piwowar M. Muscular systems and their influence on foot arches and toes alignment - towards the proper diagnosis and treatment of hallux valgus. Diagnostics, 2022 Nov 25;12(12):2945.

- Chadchavalpanichaya N, Prakotmongkol V, Polhan N, et al. Effectiveness of the custom-mold room temperature vulcanizing silicone toe separator on hallux valgus: a prospective, randomized single-blinded controlled trial. Prosthetics & Orthotics Int, 2018 Apr;42(2):163-70.

- Stewart S, Ellis R, Heath M, Rome K. Ultrasonic evaluation of the abductor hallucis muscle in hallux valgus: a cross-sectional observational study. BMC Musculoskel Dis, 2013 Dec;14:1-6.

- Menz HB, Munteanu SE. Radiographic validation of the Manchester scale for the classification of hallux valgus deformity. Rheumatol, 2005 Aug 1;44(8):1061-6.

- Garrow A, Papageorgiou A, Silman A, et al. The grading of hallux valgus: the Manchester scale. J Am Podiatric Med Assoc, 2001 Feb 1;91(2):74-8.