It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

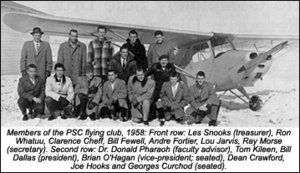

Flying Chiros, Part 1 of 2

This month, the world celebrates its 100th anniversary of aviation, in remembrance of that day at Kitty Hawk, N.C., in 1903, when Orville and Wilbur Wright made their first sustained, controlled, motor-powered flights. The evolution of chiropractic parallels that of aviation. For instance, Otto Lillienthal built and first successfully flew his biplane hang gliders in 1895, about the same time D.D. Palmer was getting chiropractic off the ground. In addition, the world wars were potent stimuli for development in both industries.1

Chiropractors have long been involved in aviation. B.J. Palmer apparently first took to the air in 1920, and was described as "an enthusiastic booster for aviation after having thoroughly studied the equipment at Wallace Field"3 in Bettendorf, Iowa. Canadian Harry A. Yates was an accomplished Royal Air Force flyer who set a record for his trip from Britain to Egypt in 1919.2,4 One of his passengers during part of the trek was Lawrence of Arabia, who was on his way to mediate between the British and the Arab tribes. Yates later served for many years as president of the licensing authority, president of the provincial association of chiropractors in Ontario, and as a member of the board of governors of the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC).

Chiropractors were active in aviation between the wars. W.E. Methvin, DC, of Tennessee, invented "an unusual slot" for his mono-wing "safety plane," which, it was purported, "prevents spinning and adds to the rate of climb and quickness of take-off."5 Several leaders of the broad-scope-tolerant National Chiropractic Association (NCA) might have hoped for a safer aircraft the following year, when they made a forced landing in a golf course:

"Dr. Gordon M. Goodfellow, NCA president, flew up from Los Angeles to the Oregon state convention in Portland recently. Dr. Howard W. Ernst was his pilot, and a good one. Sunday Dr. Ernst took Dr. and Mrs. Emery C. Ingham, Dr. D.E. Christiansen and Dr. R.D. Ketchum up for a short flight, and the motor stalled at 2,500 feet over the center of the city. Dr. Ernst made a forced landing in a small practice golf course in the center of the East side business district. Only because of Dr. Ernst's very clever flying were the passengers saved from instant death as he skimmed over the high voltage wires onto the 200-foot lot. Dr. Ernst has been flying twelve years, and this was his first crash or forced landing. He is considered a class-A pilot, and his passengers were grateful for his skillful handling of the plane and safe landing. Needless to say, Dr. Goodfellow took the train back to his home in Los Angeles.39"

Chiropractor Roy Larson made his rounds as a salesman and technician for Pathometric, Inc., a manufacturer of radionics devices, in his single-engine aircraft; he was featured in advertisements in the NCA's Journal in the 1940s. National alumnus Wayne F. Crider, DC, of Hagerstown, Md., who led the Council of State Chiropractic Examining Boards (COSCEB; the forerunner of today's FCLB) in the 1930s, and issued some of the first guidelines for the accreditation of chiropractic colleges,7 was another aviation enthusiast. He attained the rank of major in Maryland's Civil Air Patrol; he and his wife died in the crash of their private plane in rural Lancaster County, Pa., on Oct. 8, 1950.7

In the 1930s, chiropractic leaders found that commercial aviation assisted them in their professional activities, by shortening travel times greatly, in comparison with train travel. Palmer graduate John J. Nugent, DC, president of the COSCEB (when he was appointed the NCA's first director of education in 1941), made extensive use of commercial aviation to fulfill his responsibilities as inspector of chiropractic schools. Ten years later, he was said to have flown more than 180,000 miles in the line of duty, considered quite a record in an era before commercial jet travel, and worthy of mention in his hometown paper, the New Haven Sunday Register. United Airlines presented him with a plaque to honor the 100,000 miles he had logged with them.8

Dr. James C. Drain, son of the longtime president and co-owner of the Texas Chiropractic College,9 was commissioned in the Army Air Corps during World War II, and maintained his flying interest after the war. Second-generation chiropractor George Goodheart, DC, a 1939 National College graduate, also flew with the U.S. Army's Eighth and Ninth Air Forces during the "Big One," and served in the Air Force Reserve until 1956.10 He made use of various aviation metaphors in his educational seminars as the founder of applied kinesiology. "On the beam," a reference to the early electronic guidance system of triangulation used to direct bombers to their targets during the European air war, was also a popular metaphor for Thurman Fleet, DC, founder of Concept-Therapy.11 Students of Dr. Fleet were known as "beamers."

As had been true after the First World War, the second global conflict was a boon to enrollment for colleges generally, including chiropractic schools. Veterans' benefits in Canada and the United States included tuition for chiropractic studies. Classes at the newly opened CMCC in Toronto were comprised mainly of veterans, including the school's future dean, Herbert J. Vear. The young man had enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in 1942, trained as an air navigator, and flew with the RCAF Bomber Command over Germany during 1944-1945.12 He served with the RCAF reserve forces during 1961-68, and retired a major.

Dr. Vear was not the only aviation enthusiast among the administration of CMCC in the late 1960s. Robert N. Thompson, DC, MP, who graduated from the Palmer School of Chiropractic in 1939 with classmate William Harris, joined the RCAF in Alberta, was assigned as a flight instructor and attained the rank of colonel.13 Following World War II, he was instrumental in establishing the Ethiopian Air Force. He is better remembered for his supervision of a leper colony at Sheshemane, Ethiopia; election to the Canadian Federal Parliament; leadership of the Social Credit Party; service as president of CMCC; and his involvement in the founding of Trinity Western University in British Columbia, where he earned a PhD in political science at the age of 75.14

The postwar era saw a surge in aviation interest, and chiropractors were part of that trend. Philip E. Singer, DC, and his wife, Edythe, renewed their marriage vows after 25 years, while floating in a blimp 3,000 feet over Los Angeles in 1955.15 John Q. Thaxton, DC, of Raton, N.M., future president of the International Chiropractors' Association (ICA), participated as a "starter" in the third Women's National Aeronautical Association's race.16 Leonard K. Griffin, DC, a member of the ICA's Representative Assembly from Texas, and later a founding member of the American Chiropractic Association (ACA), was also an aviation enthusiast, and flew his single-engine aircraft to Palmer lyceums and on jaunts to Mexico.17 Randa Sutherland, wife of John W. Sutherland, DC, of Albuquerque, participated in air races in an aircraft that advertised the ICA.

(Editor's note: References for this article will be included at the end of part II.)

Joseph Keating Jr., PhD

Phoenix, Arizona

jckeating@aol.com