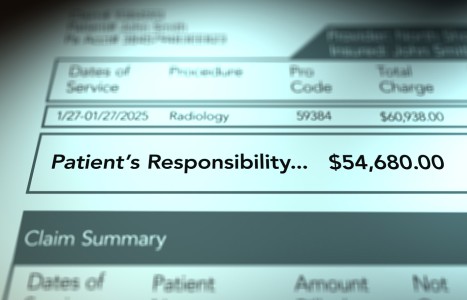

Recent laws in New Jersey and California represent a disturbing trend that will negatively impact a practice’s ability to collect monies from patients, as well as expose them to significant penalties if the practice does not follow the mandatory guidelines to a T. Please be aware that a similar law may be coming to your state. The time to act is before the law is passed.

Applied Kinesiology: How to Add Cranial Therapy to Your Daily Practice

Editor's note: This is the second in a series of three articles on applied kinesiology (three different authors); Dr. Richard Belli's "Applied Kinesiology and the Motor Neuron" appeared in the April 21 issue.

Unless a problem in the skull is severe, the majority of cranial dysfunctions are overlooked by anyone (physicians included) not trained to spot them. Although the cranium is something most doctors study in only one term of chiropractic or medical school, it seems reasonable to assume that most should know at least something about cranial dysfunctions and how to discover them. However, many chiropractors; osteopaths; family doctors; psychiatrists; and pediatricians will not notice a cranial problem, even though it may be causing serious functional disturbances in one of their patients.

School principals and teachers do not always realize the nature of the problem in a failing pupil's physiology, and may assign improper labels such as "slow learner"; "poor reader"; "dyslexic"; "poor listener"; "hyperactive"; or "poorly disciplined." Parents who spend time observing their children are more likely to notice a problem, but without knowledge of the nervous system, they cannot understand what is going on inside the child.

Many physicians are not accustomed to thinking of the brain and head as the directors of all activity, and they do not evaluate these structures during each patient visit. The idea that the cranium influences the learning abilities of children, or the sensory and postural integration of adults, is a new and strange idea to many of us. Through almost 80 years of research, many physicians have found that cranial assessments provide accurate insight into neurological organization; consequently, it may be an enviable asset for a clinician to possess the skill to quickly diagnose and accurately treat (in a single office visit) cranial faults.

Many chiropractic physicians feel intimidated by the concept of cranial evaluation and treatment. If they were more sensitive to cranial-system dysfunction, they might be better able to help their difficult patients overcome many problems related to cranial dysfunction and lead happier, more successful lives. Not only chiropractors, but also osteopaths; holistic dentists; some medical doctors (especially in Europe); physical therapists; and massage therapists actively pursue cranial manipulative procedures. With our many gifts in functional neurological assessment, more chiropractors should possess the greatest gifts in cranial evaluation and treatment.

DeJarnette and Goodheart introduced into our profession diagnostic methods for the evaluation and treatment of cranial dysfunctions.1-5 The key technical factor that has advanced cranial diagnosis and treatment, and brought the entire field of cranial therapy into accessible, reproducible, practice and scientific form, was provided by Goodheart's discovery that the musculoskeletal system and manual muscle testing (MMT) reflects what is going on within the cranial mechanism.

MMT has allowed us to discover the dramatic functional relationships that exist between the cranium and every other articulation and tissue in the body. Furthermore, patients are not treated in a "touchy feely" fashion in which the patient's skull is cradled for an indeterminate time, until the cradler perceives warmth or a yielding or softening sensation. Assurance, specificity and repeatability may be introduced into your work with the cranial mechanism. There are many other physical signs and tests (besides MMT) that also reveal cranial dysfunction; these have been written about extensively in the applied kinesiology (AK), sacro-occipital technique (SOT) and osteopathic literature. Returning the dura to a physiological range of tension by using specifically applied cranial corrections is a major goal of AK evaluation and treatment, which seeks to achieve zero defects inside and outside the cranium.

Nonetheless, with so many excellent teachers and systems of cranial treatment around, how can a doctor determine which ones are best for a given patient during a particular office visit? Where can a physician who wants to begin performing cranial therapy with patients go to access this complex system of therapy? Using MMT, this decision-making process can be accomplished, in part, by utilizing a neurological sensory-receptor challenge.

The "rebound challenge" procedure used in AK cranial diagnosis is easily explained and, with experience, easily mastered. A cranial challenge is the application of a stimulus (pressure applied by the hand or fingers, then released) to a skull bone, which leads to a specific neurological response as measured by MMT.

In Magoun's classic text on cranial therapy, Osteopathy in the Cranial Field, 3rd edition, the chapter, "Principles of Treatment" describes five different methods for "securing the point of balanced membranous tension which must be followed to secure the best results."16 The most common method is explained as follows:

"Exaggeration. This is the ordinary procedure for the usual case and is employed when not contraindicated.... To employ this method, increase the abnormal relationship at the (cranial) joint by moving the articulation slightly in the direction toward which it was lesioned.... To do this with the two members of an articulation augments the chance of securing a reduction because of the increased resilience of the membranes."

In the AK rebound-challenge procedure (which employs Magoun's exaggeration method), the physician momentarily increases the fault pattern of a single bone or group of bones, with the intention that this vector of force placed into the skull will cause a temporary increase in the tension of the reciprocal tension membranes (RTM) of the craniosacral system. If this force vector increases the RTM tension, it will produce momentary, conditional inhibition of an indicator muscle.

The cranial rebound-challenge using MMT functions in two ways: 1) It provides the doctor with a noninvasive, painless method of diagnosis; and 2) It indicates the treatment necessary to normalize the meningeal tension in the skull and around the brain.

The correction procedure is sustained through several respiratory cycles (using the same vector as found by the optimal challenge) and allows the RTM (dura, arachnoid and pia maters surrounding the brain and spinal cord) to accumulate enough energy or tension to free itself and spring back or "rebound" into the correct relationship. Magoun calls this the exaggeration correction; it is the preferred method of correction taught in chiropractic, osteopathy and craniosacral schools. This rebound correction is assisted by the patient's own breathing, which further induces the membranes into correction.

If there is a connection between the cranial system and the muscles of the head, jaw, neck or pelvis, one should observe an immediate, conditional facilitation of the muscle upon application of the appropriate sensory-receptor challenge and/or correction. You and your patient should discover in a moment the difference a cranial correction can make on the tissues of the body. For instance, to improve immediately (by a particular therapeutic trial) the tissue tone of the muscles surrounding the vertebrae, nerves and arteries of the neck; the membranes surrounding the nasal sinuses; or the tissue surrounding the jugular foramina is a real benefit in the evaluation and treatment of head and neck (eyes, ears, nose and throat) involvement. Demonstrating this change to a patient is an excellent way to raise his or her awareness of the impact of the therapy.

It is extremely difficult to localize and distinguish between the various palpated and tested tissues in the cranial area. Only by having a thorough knowledge of the external and internal anatomy of the skull can this be accomplished. However, the internal cranial tissues can be tested specifically using noninvasive AK MMT procedures, and any muscle changes can be interpreted anatomically by the physician as to the location and type of primary involvement: cranial bone; foraminal and cranial nerve entrapment; extracranial muscular involvement; etc. MMT and specific cranial and vertebral challenges offer us the best way to differentiate a cranial-bone problem from other problems in this wonderfully complex area of the body. Using MMT, a physician can make rapid, accurate and highly specific assessments of the craniosacral mechanism. Adding this mode of evaluation and treatment to your daily patient encounters can expand your scope of practice and your reputation.

For many chiropractors, evaluation of the cranial, meningeal and cranial-nerve system is not a priority. However, we know we can help many people uniquely by utilizing our skills in these areas. The application of MMT to functional neurological evaluation of the cranial system can convince ourselves, our patients and those who watch us work that what we do is effective, reproducible, scientific and occasionally miraculous.17-19 AK MMT makes work with the cranial mechanism accessible to every chiropractor.

References

- Goodheart GJ. Applied Kinesiology Workshop Procedural Manuals. Privately published, Detroit, Mich., 1964-99.

- DeJarnette MB. Cranial Technique. Privately published, Nebraska City, Neb., 1979-80.

- Walther DS. Applied Kinesiology Vol. II, Head, Neck, and Jaw Pain and Dysfunction - The Stomatognathic System. Systems DC, Pueblo, Colo., 1983.

- Walther DS. Applied Kinesiology Synopsis, 2nd edition. Systems DC, Pueblo, Colo., 2000.

- Schmitt WH, Tanuck SF. Expanding the neurological examination using functional neurologic assessment: Part II - Neurologic basis of applied kinesiology. Int J Neurosci, March 1999:97;1-2, pp77-108.

- Hubbard RP. Flexure of layered cranial bone. J Biomechanics 1971:4, pp351-63.

- Retzlaff FW, Mitchell JL. The Cranium and Its Sutures. Springer Verlag, Berlin, 1987.

- Frymann VM. A study of the rhythmic motions of the living cranium. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 1971.

- Upledger JE. Craniosacral Therapy. Eastland Press, Seattle, Wash., 1983.

- Smith GH. Cranial Dental Sacral Complex. Newtown, Pa., 1983.

- SOTO-USA, Compendium of Sacro-Occipital Technique: Peer-Reviewed Literature 1984-2000. Eastland Press 2001.

- Pederick FO. A Kaminski-type evaluation of cranial adjusting. Chiropractic Technique, February 1997:9(1), pp1-15.

- Blum CL. Biodynamics of the cranium: a survey. The Journal of Cranio-mandibular Practice, March/May 1985: 3(2), pp164-71.

- Peterson K. A review of cranial mobility, sacral mobility and cerebrospinal fluid. Journal of the Australian Chiropractic Association, April 1982:12(3), pp7-14.

- Pederick FO. Developments in the cranial field. Chiropractic Journal of Australia, March 2000:30(1), pp13-23.

- Magoun HL. Osteopathy in the Cranial Field, 3rd edition. Sutherland Cranial Teaching Foundation, Meridian, Idaho, 1976:100.

- Rosen MS. Research status of applied kinesiology, part 1. Dig Chiro Econ, Sept./Oct. 1994:37(2), pp17-23.

- Williams L, Rosen MS. The research status of applied kinesiology, part 2: an annotated bibiloiography of applied kinesiology research. Dig Chiro Econ, May/June 1995:37(6), pp40-44.

- Index of the collected papers of the members of the ICAK. ICAK-USA, Shawnee Mission, Kan.