New York's highest court of appeals has held that no-fault insurers cannot deny no-fault benefits where they unilaterally determine that a provider has committed misconduct based upon alleged fraudulent conduct. The Court held that this authority belongs solely to state regulators, specifically New York's Board of Regents, which oversees professional licensing and discipline. This follows a similar recent ruling in Florida reported in this publication.

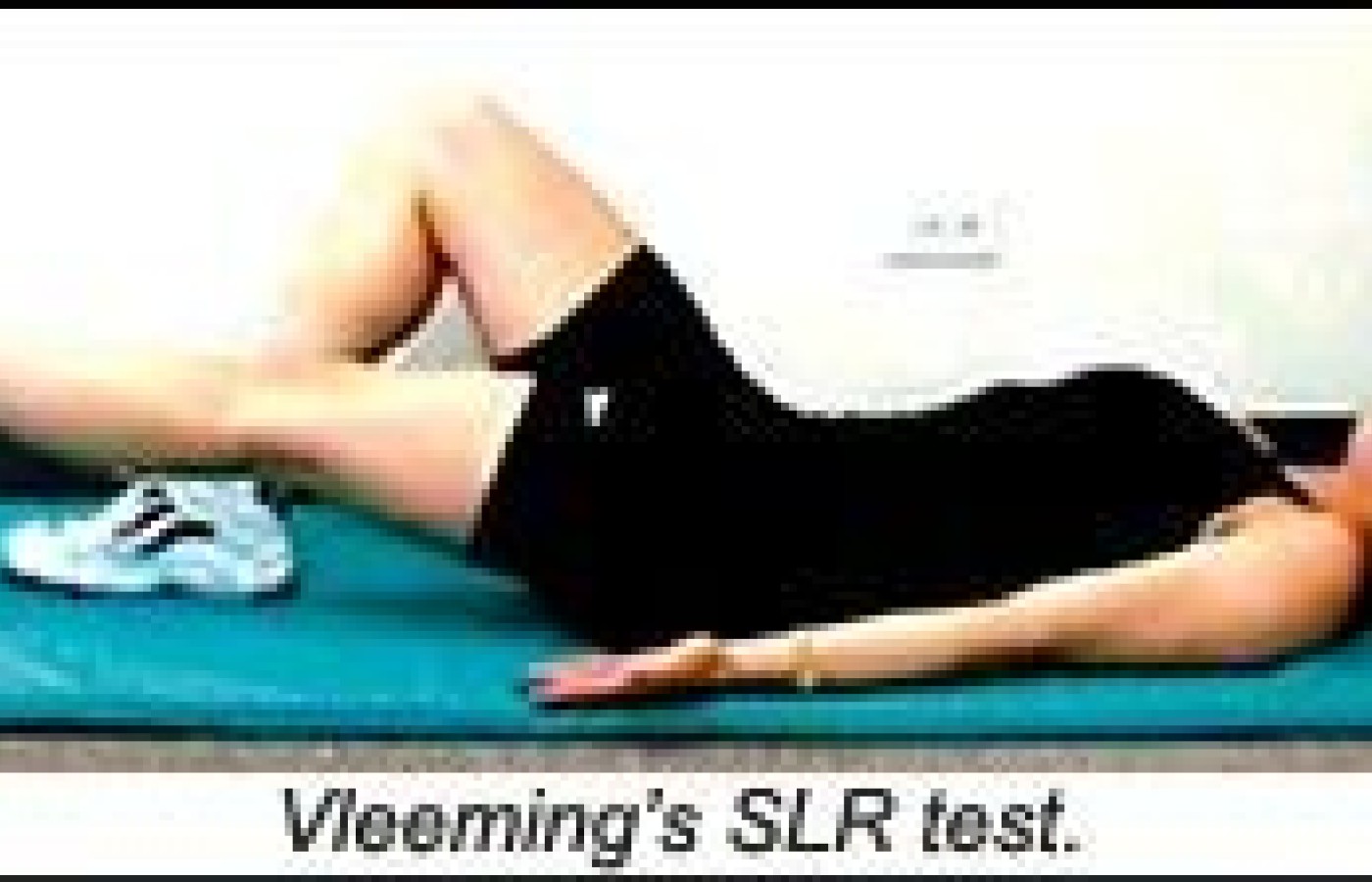

Vleeming's Active SLR Test as a Screen for Lumbopelvic Dysfunction

Introduction

Finding the functional diagnosis that explains our patients' symptoms and activity intolerances can prove challenging in the clinical setting. Functional screening tests are invaluable for identifying "key links" responsible for the biomechanical overload of pain-sensitive structures. A unique variation on the straight leg raise (SLR) test has emerged from Europe, which can be utilized to screen for lumbopelvic dysfunction in back pain patients.

The Relationship of Mechanical Sensitivity, Structural Pathology and Dysfunction

If a patient presents to our clinic with back and/or buttock pain, can we count on range of motion, palpation or orthopedic tests to reveal what is causing the patient's pain, or is it more likely that this exam will tell us about the patient's mechanical sensitivity? These procedures may reveal what the pain generator is, but not what has caused that tissue to become painful in the first place.

Similarly, is it realistic to assume that imaging modalities will inform us about the source of this patient's biomechanical overload? If the false-positive rate for herniated discs and arthritis is 20 percent in 20-year-olds; 30 percent in 30-year-olds; 50 percent in 50-year-olds; and so on, can we assume positive findings as the actual cause of our patients' pain? It is more likely that an individual's ability to adapt to structural pathology is related to how functional he or she is. In contrast, those who do have symptoms have pain precisely because they are not adapting or functioning well!

For this reason, clinicians are charged with the challenge of finding the relevant dysfunction responsible for structural pathology, or a potential pain generator becoming biomechanically overloaded.

Vleeming's Straight Leg Raise Test

The Dutch scientist Andry Vleeming has developed a variation on the SLR to assess lumbopelvic and/or sacroiliac (SI) dysfunction. This new version of the SLR has demonstrated its reliability and validity for revealing relevant dysfunction in the kinetic chain of low back or pelvic pain patients.1 Sensitivity was 0.87 and specificity was 0.94.1

The active straight leg raise test (ASLR) has been shown to be associated with postpartum SI pain. It has been shown that altered kinematics of the diaphragm and pelvic floor are present in those with a positive test.2 Additionally, manual compression, lateral-to-medial, through the ilia, normalizes these altered motor control strategies.2

Test: Have the supine patient perform the SLR 20 cm using the following instruction: "Try to raise your legs, one after the other, above the couch for 20 cm without bending the knee." Note if there is:

- pain; or

- significant trunk rotation.

If the test is negative, add resistanceand see if there is pain or trunk rotation,

- grade strength _/5.

If either test is positive, try the following and recheck if the test is negative:

- have the patient actively brace his or her lumbar spine;

- apply manual compression through the ilia; and

- tighten a belt around the pelvis.

Clinical Consequences

Pain or poor motor control during ASLR is caused by SI joint dysfunction or abdominal or hip flexor inhibition. The kinetic chain consequence of a positive test is altered load transfer from leg to trunk, and poor stability during gait; lunging; kneeling; squatting; pushing; and pulling activities.

The SI joint provides stability to the locomotor system during gait through two mechanisms. Form closure occurs because of nutation and counternutation of the pelvis during gait or other load transfer from leg to trunk. Force closure occurs through muscle slings that corset the lumbopelvic region during such load transfers. These muscle slings run anteriorly (pectoralis major, external oblique, transverse abdominus, internal oblique) and posteriorly (gluteus maximus, latissmus dorsi).

Treatment:

- SI adjustment;

- piriformis, adductor, tensor fascia lata, psoas postisometric relaxation and self-stretches;

- SI belt;

- abdominal bracing exercises;

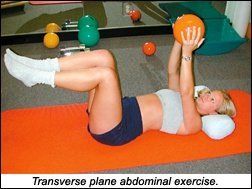

- muscle sling exercises (transverse plane abdominal, pushing, pulling);

- bridge; and

- quadruped opposite arm and leg reaches.

References

- Mens JMA, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, Koes BW, Stam HJ. Reliability and validity of the active straight leg raise test in posterior pelvic pain since pregnancy. Spine 2001;26:1167-1171.

- O'Sullivan PB, Beales DJ, Beetham JA, Cripps J, Graf F, Lin IB, Tucker B, Avery A. Altered motor control strategies in subjects with sacroiliac joint pain during the active straight-leg-raise test. Spine 2002;27:E1-E8.

- Mens JM, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, et al. The active straight-leg-raising test and mobility of the pelvic joints. Eur Spine J 1999;8:468-74.

- Mens JMA, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, et al. Active straight-leg-raise test: A clinical approach to the load transfer function of the pelvic girdle. In: Vleeming A, Mooney V, Dorman T, et al., eds. Movement, Stability and Low Back Pain: The Essential Role of the Pelvis. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1997:425-31.

Craig Liebenson, DC

Los Angeles, California

cldc@flash.net