Some doctors thrive in a personality-based clinic and have a loyal following no matter what services or equipment they offer, but for most chiropractic offices who are trying to grow and expand, new equipment purchases help us stay relevant and continue to service our client base in the best, most up-to-date manner possible. So, regarding equipment purchasing: should you lease, get a bank loan, or pay cash?

Neck Pain and Whiplash: Exercise Progressions for WAD

The incidence of chronic neck pain and related symptoms following an acceleration / deceleration injury is well-established in the literature: upwards of 40 percent. Headaches, neck pain, TMJ disorders, anxiety, depression, medication overuse, neurological complaints and overall neck disability are all classified as whiplash-associated disorders (WAD).

A multimodal approach to treating WAD includes CMT at the crux with lifestyle modifications, nutrition, soft-tissue work, taping / bracing and therapeutic exercise as the spokes of the wheel. The studies also indicate that an individualized, progressive exercise program is superior to a generalized program.

Exercise for WAD

Exercise for WAD is important since it reinforces the benefits of CMT, enabling adjustments to "hold" better. Ligaments account for only 25 percent of cervical spine stability; therefore, it is the deep neck muscles which provide a majority of support for the neck both statically and with motion. Creating strength, endurance and balance in the cervical musculature is essential to maintain neutral vertebral juxtaposition, whereby loading is optimally distributed over all supporting structures.

Flexion vs. Extension Exercises

In 2019, Suvarnnato, et al., placed chronic WAD patients into one of three training groups: control, deep cervical flexor strengthening, and semi-spinalis cervicis (extensor) training. He found both the cervical flexor and extensor training groups were effective in reducing pain and disability compared to the control group. Furthermore, he underscored the importance of deep cervical flexor (longus colli and, longus capitus) training in the treatment of forward head posture (FHP) by increasing stability and improving the craniovertebral angle.

The extensor group also showed improvement. Extension exercises increase stability, proprioception and mechanoreceptor input, which ultimately restores sensorimotor control of the cervical spine. The bottom line is both flexion and extension exercise are important to restore strength, stability and sensorimotor control when treating WAD; and the doctor needs to individualize the exercises to the patients.

Clinical Tip: Patients with FHP benefit from deep cervical flexor exercises. The ratio of strength between the cervical flexors to extensors, as well as the lateral flexors, needs to be symmetrical: within 10 percent front to back and right to left.

Phases of Progression

The chronic pain patient is often deconditioned due to inactivity and fear-avoidance behaviors. This can make the introduction of active care difficult. Intensity, frequency, load and overall volume need to be balanced to achieve progressive improvement without creating an acute inflammatory reaction.

These patients also need to understand that pain with activity does not equal harm. Progressive loading and positive reinforcement are techniques to keep the chronic pain patient on track.

Landen-Ludvigsson has developed a WAD progressive rehabilitation program that has been shown to be effective and begins with simple eye movement and auto correction This procedure is excellent for the chronic patient with fear avoidance.

She teaches them to find neutral sagittal alignment supine using a towel under the head as needed and then begins a series of eye exercises without neck motion: looking up toward extension, looking down toward flexion, and looking to the sides as if in rotation. Each position is held for five seconds.

The second phase of her program is still supine, but isometric contraction of the cervical muscles is added in the direction of the eye movement. Again, no cervical spine movement is allowed. Essentially, the patient looks up and isometrically contracts the neck; looks down into flexion and isometrically flexes the neck; and does the same with right and left rotation. For rotation and for flexion, the patient uses their hands to provide resistance without neck motion.

Clinical Tip: To provide joint stability, isometrics are best performed at 25 percent maximal voluntary contraction and held for 7-8 seconds. A gentle ramp up and down, 1-2 seconds, is recommended. Start with one set of six and build to three sets of 15.

The third progression involves maintaining sagittal plane alignment while the patient is on an incline bench – a high / low chiropractic table partially elevated works well, too. This engages the core muscles and prepares the patient for maintaining sagittal lane alignment under gravity and additional load. The more vertical the bench or table, the less effort. Patients begin with a higher incline and as they improve, progress to a flat bench or the floor.

The fourth progression involves doing exercises with an external load with either a pulley system or elastic resistance. The patient is instructed in the office and progresses to a home exercise prescription in sitting and standing.

Clinical Tip: Isometrics can be progressed by adding external load to the position with elastic resistance, gravity or cable systems depending on the body part. Called "reactive isometrics," it is an excellent transition from isometric to isotonic movements.

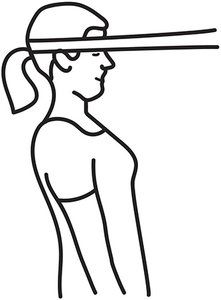

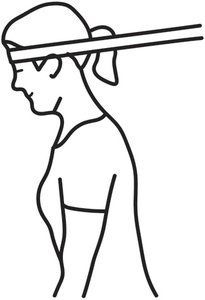

Using elastic resistance for strengthening involves establishing sagittal plane alignment and then maintaining it as the patient leans from the waist against resistance. This allows the patient to load the neck in flexion, extension and lateral bending while creating stability. These exercises are an advanced isometric load on the neck.

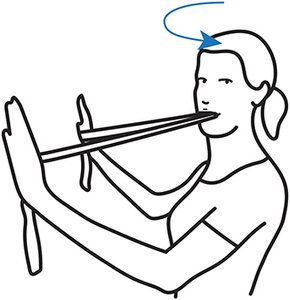

Rotation with resistance is performed by holding the ends of the resistance band against the wall at chin height with the middle of the band being gently held between the teeth. Again, all exercises are done with optimal sagittal plane alignment. [See Figures 1-4]

This protocol is excellent for the chronic WAD patient because it addresses many facets within the rehabilitation continuum:

- Eye movements promote neurologic repatterning, preparing the patient for active care.

- Auto correction of sagittal plane alignment, essential in forward head posture correction, is introduced immediately and continued throughout.

- Isometrics reduce joint shear while strengthening.

- Progressing from exercising without gravity to against gravity is appropriate.

- Increasing load is easily done in the office and at home with elastic resistance.

Take-Home Points

The chronic pain patient is challenging. They need guidance, support and numerous services within our office – CMT, supplements, supports / bracing, soft-tissue work and follow-up care, to name a few. They may also require co-management with other providers. Understanding the application of these corrective exercises is a safe starting point for active care.

Resources

- Landen Ludvigssson M. Detailed exercise progression for whiplash-associated disorder. (Email me for a copy of this progression.)

- Landen Ludvigssson M, et al. Exercise, headache, and factors associated with headache in chronic whiplash: analysis of a randomized, controlled trial. Med, 2019 Nov;98(48):e18130.

- Liebenson C. Rehabilitation of the Spine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippinoctt, Williams Wilkins, 2007.

- Suvarnnato T, et al. Effect of specific deep cervical muscle exercises on functional disability, pain intensity, craniovertebral angle, and neck muscle strength in chronic mechanical neck pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Res, 2019;12:915-925.