New York's highest court of appeals has held that no-fault insurers cannot deny no-fault benefits where they unilaterally determine that a provider has committed misconduct based upon alleged fraudulent conduct. The Court held that this authority belongs solely to state regulators, specifically New York's Board of Regents, which oversees professional licensing and discipline. This follows a similar recent ruling in Florida reported in this publication.

Assessment Tools: The Overhead Squat

Editor's Note: Previous articles in this four-article series appeared in the January, March and August 2019 issues.

This is the fourth and final article in this series on squat mechanics, designed to give the DC a comprehensive understanding of the squat as a foundational exercise, its use as a functional assessment tool, and common deficits and corrective interventions that can be used in everyday practice.

The overhead squat assessment (OSA) is an advanced squat assessment tool that has greater sensitivity than the back squat assessment (BSA, discussed in previous articles) in developing corrective exercise prescriptions. This will further enhance your knowledge of "the squat" as not just a foundational exercise, but also an effective functional assessment tool.

Performing the Assessment

The OSA is performed in four positions in stocking feet, with the feet hip-width apart. Removing the shoes reduces the pedal foundation, enabling lower-leg imbalances to be readily observed. The verbal instructions are for the patient to squat to chair height or up to parallel (not below, as this is not a deep squat) in the following sequence:

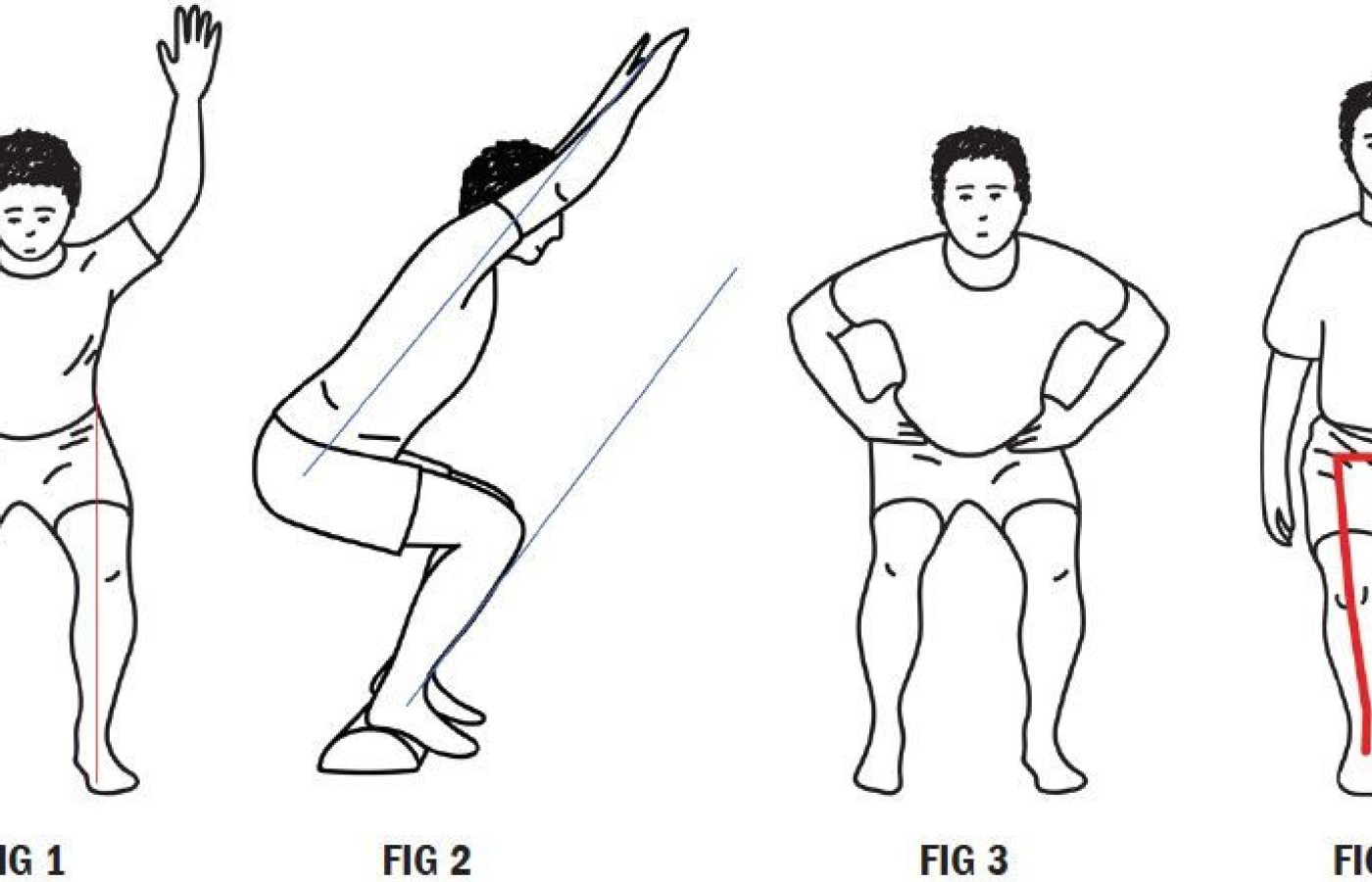

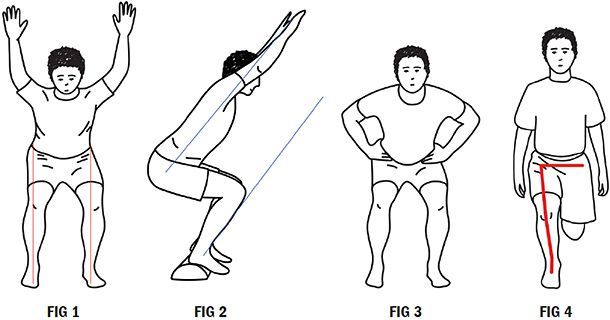

- The "baseline" position for the OSA is to have the patient squat with arms raised overhead, "covering the ears" from the lateral view. (Fig. 1)

- Patient performs a squat with the arms overhead and heels elevated approximately 2-3 inches. A ½ foam roller works perfect. (Fig. 2)

- Patient squats with feet flat on the floor and hands on the hips. (Fig. 3)

- Patient performs a single-leg ¼ squat. Note: When done with hands on hips, the upper domain is less engaged. (Fig. 4)

|

|

|||

|

Deficit

|

Probable Tight Muscles & Joint Restrictions (CMT Needed)

|

Probable Weak Muscles

|

Suggested Corrective Actions

|

|

|

|||

| Asymmetrical Pelvic Shift |

Side of Shift:

AdductorsTFL Opposite Side of Shift:

PiriformisGluteus medius Biceps femoris |

Side of Shift:

Gluteus mediusOpposite Side of Shift:

Adductors |

Lateral band walks Wall squats Gluteus medius (same side) Adductors (opposite side) CMT hip / ankle Hip flow routines |

|

|

|||

| Hip Drops in ¼ Squat |

Opposite Side of Drop:

Quadratus lumborum |

Opposite Side of Drop:

Gluteus medius |

Split squats Single-leg bridges Clamshells CMT hip |

|

|

|||

| Hip Hikes in ¼ squat |

Side of Drop:

Quadratus lumborum |

Opposite Side of Drop:

Gluteus medius |

Sit touches Hip hinge CMT ankle |

|

|

|||

Anatomical Checkpoints

The anatomical checkpoints in the OSA in all four positions are similar to the previously described checkpoints for the BSA. Anteriorly, the head, shoulders and pelvis remain level, while the knees track over the feet maintaining the hip, knee, foot line. Laterally, the torso / tibia lines are parallel, the lumbar spine remains in neutral, the arms (when overhead in positions 1 and 2) still "cover the ears" and there is appropriate anterior tibial translation. Posteriorly, there is no lateral shift of the pelvis, the feet do not flatten or roll out, and the heels do not elevate.

Key Information Obtained

The OSA with the arms overhead provides the following additional information not obtained in the BSA:

- ROM of the shoulders

- Quality of shoulder flexion; specifically, whether the patient can perform "pure" shoulder flexion in a symmetrical manner without upper trapezius overactivity, scapular winging or extension in the spine or rib cage

- Functional shoulder stability with compound motions; specifically, can the patient maintain full shoulder flexion while performing the squat or do the arms fall forward?

Figure 2 demonstrates squatting with the heels elevated and arms overhead, which provides essential information about the lower leg, ankles and feet. If the squat improves with the heels elevated, there is either tightness in the posterior calf musculature or limited dorsiflexion of the ankle, impacting proper squat mechanics.

Placing the hands on the hips and squatting, as in Figure 3, removes the latissimus and other upper back musculature from stabilizing the torso. Placing the hands on the hips often highlights hip flexor and anterior chain dominance / tightness, and is demonstrated by an excessive forward lean as compared to squatting with the arms overhead.

Single-leg quarter squats with the hands on the hips is essentially a dynamic Trendelenburg test, loading the entire lower extremity. Pelvic unleveling from weak gluteus medius or over active quadratus lumborum muscles is readily evident, as is valgus shifting of the knee and pedal pronation. When present, a valgus knee shift and pedal pronation implicate additional weakness in the lower leg beyond proximal dysfunction in the pelvis. Finally, rotation of the torso in the coronal plane in this position indicates an imbalance between the internal and external obliques.

Regardless of the deficit present, it needs to be addressed. See the chart for common deficits and corrective actions. The corrective actions discussed in the previous articles for the upper and lower domains all apply to the OSA and the single-leg imbalances discussed above.

The last movement deficit to discuss is a lateral shift of the pelvis during the OSA. As with any imbalance, a lateral shift of the pelvis can be the result of poor motor control or kinetic chain imbalances.

For example, loss of ankle dorsiflexion will cause a shift to the opposite side; an imbalance that reduces when the heels are raised. On the other hand, a weak gluteus medius will cause the pelvis to shift to the same side – an imbalance that reduces with gluteus medius strengthening.

The technique in developing a corrective exercise program with the OSA is to observe for patterns of deficits that point to primary areas of weakness, tightness or pathomechanics.

Clinical Takeaway

This series on the squat has been focused on corrective exercises to improve mechanics and movement. Training movement patterns for everyday life is the domain of the OSA, which enables you to train your patient's entire kinetic chain to move better so they can move more.

The OSA is an effective assessment tool that can be used as a baseline for treatment, as well as pre- and post- treatment. The corrective actions discussed in previous articles for the upper and lower domains all apply to the OSA.

The squat is an excellent foundational exercise for ADLs and sport. The OSA is a simple tool to bring your BSA to the next level and integrate corrective exercise prescriptions into your practice today.

Author's Note: For a one-page tear-sheet answer key for the OSA, email me directly (see email address in bio). For more information, watch the Squat Playlist on my You Tube Channel – www.YouTube.com/DrDeFabio.

Resources

- Clark MA, Corn RJ, Lucett SC. NASM Essentials of Corrective Exercise. Calabasas, CA, 2007.

- Kritx M, Cronin J, Haume P. The bodyweight squat: a movement screen for the squat pattern. J Strength Cond, 2009, Feb 31;(1):78-85.

- Myer GD, Kushner Am ,Bren JL, et al. The back squat: a proposed assessment of functional deficits and technical factors that limit performance. Strength Cond J, 2015 Dec 1;36(6):4-27.