It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

How to Predict Knee Injuries (and Then Prevent Them)

In any given year, nearly one in 25 athletes will tear their anterior cruciate ligament.1 More commonly, one in 10 recreational athletes develop patellofemoral pain annually, and once diagnosed, more than 90 percent will continue to suffer with chronic knee pain years later.2 To make matters worse, individuals with ACL tears and/or patellofemoral pain are significantly more likely to develop arthritis later in life.3

Prediction: The Right Test

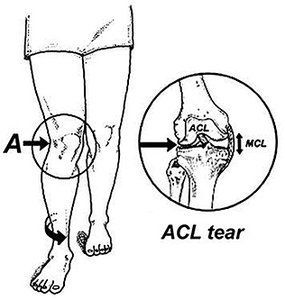

Fortunately, new research shows it is possible to identify at-risk athletes with a simple muscle test using a hand-held dynamometer.4 Because anterior cruciate ligaments are associated with excessive hip internal rotation and valgus collapse of the knee during stance phase (Fig. 1), researchers from Iran theorized that athletes prone to tearing their anterior cruciate ligaments would present with weak hip abductors and rotators, and would therefore be less likely to muscularly control their lower extremities while participating in sport.4

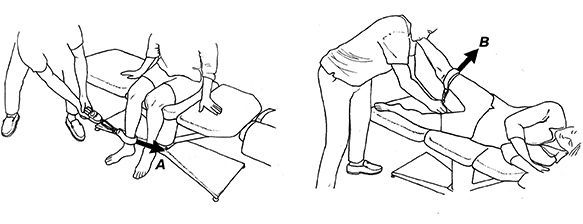

To test their theory, these researchers followed 531 competitive athletes (138 females and 363 males) participating in various sports for one season after measuring hip strength with a hand-held dynamometer. The specific muscle tests are illustrated in Fig. 2. Athletes were classified as "strong" if they could generate more than 20 percent and 35 percent of their body weight in their hip rotators and abductors, respectively. Conversely, athletes were classified as "weak" if they failed to meet these minimum hip strength requirements.

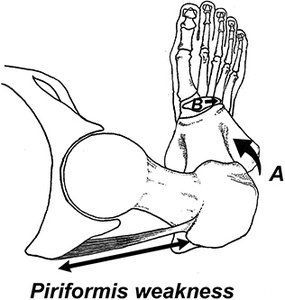

Using the strength measurements based on body weight, the researchers discovered that at the end of the season, fewer than 1 percent of the strong athletes had suffered ACL injury, while 7 percent of athletes with weak hips tore their ACLs. Having a weak piriformis muscle was especially correlated with increased rates of ACL tears. This is consistent with prior research confirming that isolated piriformis weakness strongly correlates with the development of a wide range of lower extremity injuries,5 including patellofemoral pain syndrome. (Fig. 3).

Prevention: The Right Exercises

Knowing in advance which athletes are prone to ACL and/or retropatellar injuries is incredibly important because there are proven exercise interventions that markedly reduce injury rates. For example, Gilchrist, et al.,6 was able to reduce ACL injuries by 70 percent in 1,435 Division I college female athletes by having them perform a series of simple agility drills.

More recently, Baldon, et al.,7 had women with chronic retropatellar pain perform specific functional exercises to strengthen their hips and knees. Not only did these exercises reduce pain and improve function; they also reduced valgus collapse of the knee while exercising. Interestingly, these authors compared the functional exercises with conventional physical therapy exercises targeting the hips and knees (such as leg presses, seated knee extensions and straight-leg raises), and only the functional movement patterns improved three-dimensional movement patterns.

Clinical Pearls

Considering the long-term physical and emotional consequences associated with ACL and/or patellofemoral injuries, every athlete should be tested preseason to quantify hip strength ratios. Weak athletes should be encouraged to perform specific training protocols to reduce their potential for injury. Measuring hip rotator / abductor strength with a hand-held dynamometer is easy and reliable, and subsequent testing during re-examination can help evaluate response to a specific exercise intervention.

Author's Note: A video of exercises that specifically target the piriformis and gluteus medius is available at www.humanlocomotion.org.

References

- Moses B, Orchard J, Orchard J. Systematic review: annual incidence of ACL injury and surgery in various populations. Res Sports Med, 2012;20(3-4):157-179.

- Stathopulu E, Baildam E. Anterior knee pain: a long-term follow-up. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2003;42(2):380-382.

- Utting MR, Davies G, Newman JH. Is anterior knee pain a predisposing factor to patellofemoral osteoarthritis? Knee, 2005;12(5):362-365.

- Khayambashi K, Ghoddosi N, Straub R, et al. Hip muscle strength predicts noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury in male and female athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med, 2015;(44):355-361.

- Leetun D, Ireland M, Willson J, et al. Core stability measures as risk factors for lower extremity injury in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2004;36:926-934.

- Gilchrist J, Mandelbaum H, et al. A randomized controlled trial to prevent noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury in female collegiate soccer players. Am J Sports Med, 2008;36:1476-1483.

- Baldon R, Serrao F, Silva R, Piva S. Effects of functional stabilization training on pain, function, and lower extremity biomechanics in women with patellofemoral pain: a randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2014;44(4):240-251.