It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

The Back Squat: More Than a Training Exercise

The squat movement pattern is not only essential for ADLs; it is considered a foundational exercise for strength, resiliency and sport performance. Furthermore, the basic squat is a single compound maneuver that is highly sensitive to biomechanical deficits, making it an excellent movement assessment for active care.

Myer and his team have proposed that the back squat is more than a conditioning exercise; applied properly, it is a dynamic screening tool that can isolate functional deficits, serve as a guide in rehabilitation and direct corrective exercise prescriptions.

The Back Squat Assessment

The unloaded Back Squat Assessment (BSA) is divided into three comprehensive domains: upper body (head, neck and torso), lower body, (hips, knees and ankles) and movement mechanics (timing, coordination and recruitment patterns). Each domain is graded for neuromuscular, strength and mobility deficits. The patient is assessed from the anterior, posterior and lateral perspectives, and the test is performed for 10 repetitions.

Meyer suggests video analysis as a valuable tool to assess all planes of motion. A positive finding is failure to perform the desired technique on two repetitions. As with any functional assessment, if the BSA provokes pain, the test is discontinued until the underlying pain driver is addressed.

The BSA is performed without load since proper squat mechanics need to be established and biomechanical deficits corrected before a patient can progress to more advanced squat variations. By grooving optimal movement patterns before load is applied, both injury resilience and performance are increased.

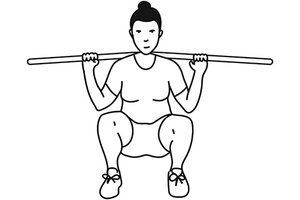

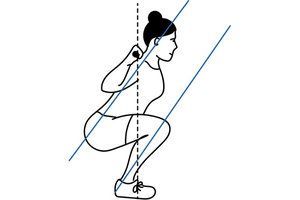

As with any test, normative values must be defined so imbalances can be isolated and progress can be monitored. In administering the BSA, it is paramount that the patient's arm, torso and stance, as well as the verbal cues used, are standardized. Details are provided below [and depicted in the illustrations that accompany this article: anterior, posterior and lateral views, respectively].

Arm and Hand Positioning

- Pronated grip on a dowel (metal, wood or plastic, approximately 36" x 1.25"), hands slightly wider than shoulder width.

- Rest the dowel across the posterior deltoids just below C7.

- Forearms parallel to the torso and wrists straight.

- "Bend the bar" – patient pulls the bar into the trapezius, and tightens the scapular retractors, depressors and latissimus (essentially creating additional core stability).

- If a dowel is not available, patient places their hands open palmed under their ears while retracting the scapulae.

Appropriate Stance

- Heels approximately shoulder-width apart and toes pointing forward.

- Maximum of 10 degrees of external rotation of the feet are allowed.

- Heels and forefoot kept on the ground.

Note: Meyer finds this moderate stance appropriate since research documents an excessively narrow stance may increase forward knee translation and heighten anterior shear forces; and a wide stance may increase patellofemoral and tibiofemoral compressive forces in the knee joint by up to 15 percent during descent.

Upper-Body Positioning

- Head and neck in neutral alignment to slight extension, in line with the torso.

- Gaze: slightly upward with a neutral head position.

- Thorax: chest up, thoracic spine slightly extended and held rigid. Scapulae are retracted and depressed with the patient's forearms parallel to the spine.

- Lumbar spine and trunk: neutral alignment throughout the entire squat movement. From the lateral view, the line of the trunk is maintained parallel to the line of the tibias during both descent and ascent.

Note: A trunk that is unsteady and moves out of an upright position during the squat may be indicative of internal core weakness. Furthermore, excessive anterior or posterior tilt of the pelvis is best assessed when the patient squats to at least parallel.

Lower-Body Positioning

- Neutral pelvic tilt is maintained throughout the entire squat movement.

- Hips: square and stable with minimal mediolateral movement.

Note: Lack of hip mobility is often manifested as an increase in torso flexion in the decent phase. Dowel dropping on one side may also indicate a unilateral hip, knee or ankle dysfunction.

- Femurs: symmetrical movement without internal or external rotation.

- Knee, frontal plane: track over the toes; no medial or lateral displacement.

- Knee sagittal plane: anterior translation that is parallel to the trunk.

Note: While an increased anterior tibial translation increases torque at the knee, there is no established degree of knee flexion directly related to an increased injury risk during the squat. Therefore, the accepted indicator for anterior tibial translation is to maintain the tibial angle parallel to the torso.

- Feet: remain flat and stable on the floor throughout the squat.

Note: Remember that foot and ankle function are influenced by proximal forces, so be sure to consider the entire kinetic chain. For example, a tight biceps femoris can manifest as external rotation of the lower leg and foot.

Verbal Instructions

"Please stand upright with feet shoulder-width apart. Squat down until you believe the top of your thighs are parallel to the ground, and then return to the initial starting position. Perform 10 continuous repetitions at a consistent, moderate pace or until you are instructed to stop."

Before the descent, the patient is instructed to take an 80 percent full breath and attempt to hold it throughout the test. This will increase intra-abdominal pressure and, in conjunction with the bend and bow of the dowel, creates spinal stiffness, which in turn will assist in grooving normal mechanics.

The Descent

The descent needs to be smooth and controlled, with a 2:1 ratio to the ascent, emphasizing the eccentric component of the exercise. Squat depth is determined by quality of the squat, with the goal of achieving femurs slightly past parallel to the ground, hips back, tibial line parallel to the torso line (lateral view illustration) and feet entirely on the ground. Adequate squat depth is required to maximally engage the hamstrings and gluteal complex, but cannot be sacrificed for poor execution.

The Ascent

During the ascent phase, the torso needs to remain upright, shoulders and hips need to rise at the same pace, and the difference in vertical height of the shoulders and hips should remain constant. The back is to be kept rigid and tight while focusing on driving with the hips to ascend.

Clinical Takeaway

While subsequent articles in this series will review corrective interventions for imbalances, remember that the back squat is a learned skill, and the first intervention for asymmetries is verbal and tactile cueing to develop the psychomotor skill of the movement. A mirror, static pictures or video analysis are all excellent tools to incorporate, as well as simple instructions such as, "Keep your chest up and shoulder blades pulled back," "Point your kneecaps straight ahead" or "Keep your neck straight – only look up with your eyes." Imbalances that persist after simple cueing imply corrective exercises, CMT, soft-tissue work and activity modification need to be incorporated.

The back squat is the mainstay of exercise programs for wellness, fitness, performance and ADLs. Meyer's concept of using the unloaded back squat as an assessment tool can be easily incorporated in the active chiropractic treatment plan for most, if not all, of our patients.

Author's Note: For more information, watch the squat assessment video section on my YouTube channel.

Reference

- Myer GD, et al. The back squat: a proposed assessment of functional deficits and technical factors that limit performance. Strength Cond J, 2015 Dec 1;36(6):4-27.