New York's highest court of appeals has held that no-fault insurers cannot deny no-fault benefits where they unilaterally determine that a provider has committed misconduct based upon alleged fraudulent conduct. The Court held that this authority belongs solely to state regulators, specifically New York's Board of Regents, which oversees professional licensing and discipline. This follows a similar recent ruling in Florida reported in this publication.

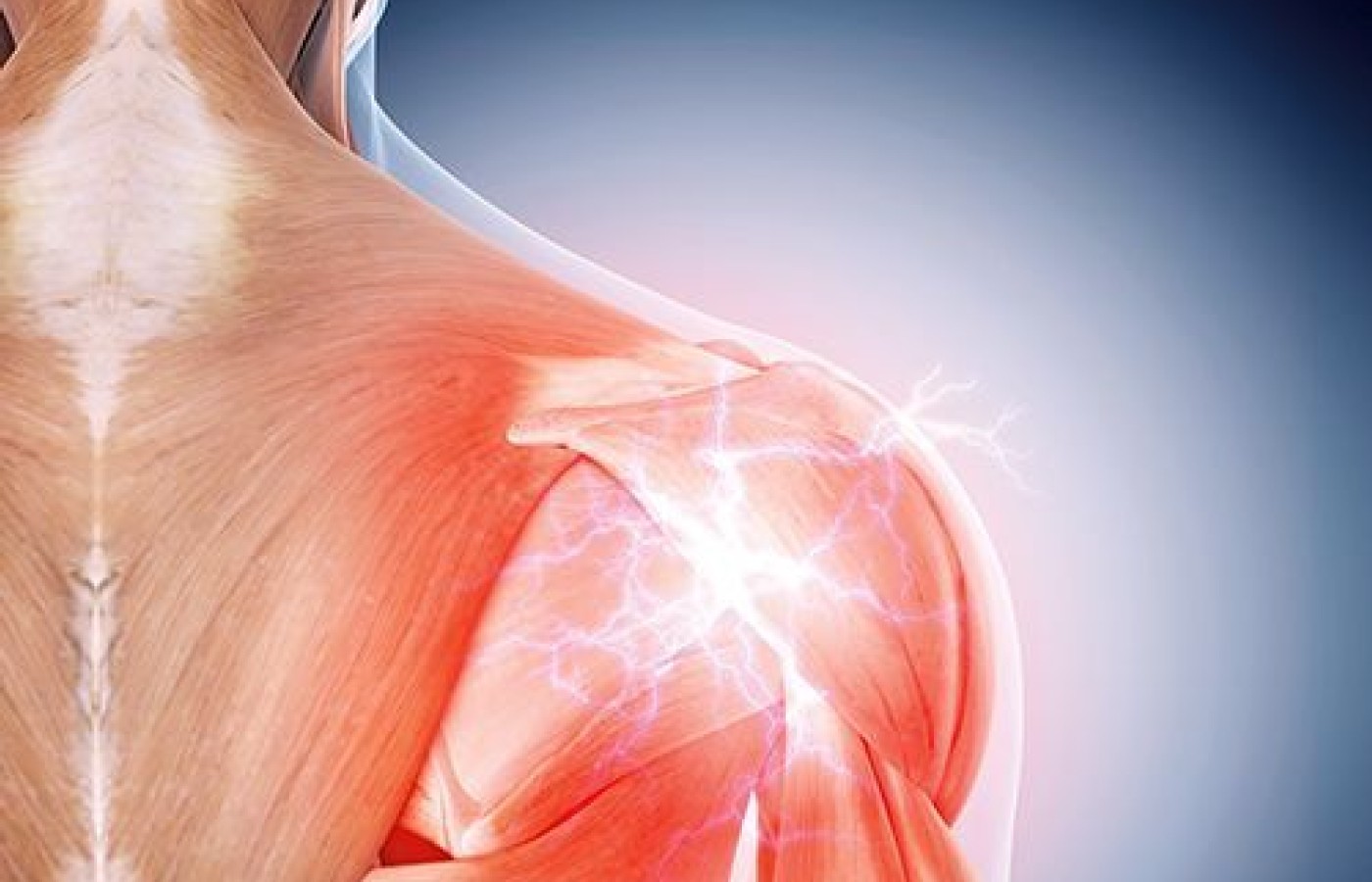

Shoulder Rehab: The Gait Connection

Shoulder problems can be difficult to rehab completely for several reasons. The shoulder is made up of several joints that must function together smoothly to provide the extreme mobility that is possible and necessary for many activities. First, it is not easy to determine which of the many tissues involved in shoulder function require rehabilitation. Second, the patient often is unable (or unwilling) to perform the many exercises we recommend. And third, adjustments and exercises do not always bring about a full recovery, especially in chronic shoulder conditions.

Because it is an extremely mobile joint with little inherent stability in certain positions, the shoulder region can be easily injured during athletic and recreational activities, at work or in a fall. Every acute sprain and strain injury to the shoulder must be properly treated and fully rehabilitated if future problems are to be avoided. Chronic instability is a real possibility after an injury, since many patients do not regain full function.

It is important to regain full neurological coordination of the surrounding muscles and connective tissues, since that is the true source of shoulder joint stability. An often-overlooked component of shoulder muscle re-coordination is the connection with spinal movements and gait rhythm.

How the Shoulder Functions

The shoulder joint complex includes the acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular, glenohumeral and scapulothoracic articulations. There are many muscles in this complex, including 17 that have attachments on the scapula. The upper thoracic spine also should be considered a major contributor to shoulder motion, especially during overhead reaching (when reach is extended as the spine tilts away from the shoulder) and during throwing.1

The connective and muscular tissues that support and move these joints will need to be assessed and eventually, rehabilitation of all injured tissues will be necessary in order to regain full function. It is the rotator cuff that keeps the axis of motion of the humeral head in the glenoid fossa consistent, thereby preventing pathologic mobility and biomechanical injury.2

The scapula plays a significant role as anchor for the rotator-cuff muscles. Its movement helps to keep the strength / length tension relationships advantageous for the musculature. And while the scapula functions as an anchor, it also moves. Movement of the scapula is directly affected by the relative body position, overall posture and gravity’s downward pull. This means trunk inclination, as well as torso and neck postures, are important factors in normal function.

Traditional Shoulder Rehabilitation

Usual methods of shoulder rehabilitation have focused on the use of resistance exercises to progressively strengthen the rotator cuff and all of the muscles that move the shoulder joints. Initially, expensive machinery that isolated the muscles was thought to be necessary. Today, we know that elastic tubing or bands can be a safe and effective method of providing progressive resistance exercises; several leading chiropractic equipment companies offer these inexpensive, effective devices.2

An easy and often-used program starts with a consistent isotonic exercise routine. This is initially performed within a limited, pain-free range of motion, building to full range as pain subsides. Eventually, the entire series of shoulder exercises should be performed.

This inexpensive rehabilitation program should initially be practiced under supervision to ensure proper performance. Once good exercise mechanics and control are demonstrated, a self-directed program of home exercises is appropriate.

Newer Shoulder Rehab Concepts to Consider

A factor that is too frequently overlooked, however, is the influence of posture on shoulder girdle function. Reports by Hertling and Kessler,3 and Hammer,4 support the need to evaluate the patient for specific postural distortions that interfere with shoulder function, such as thoracic kyphosis and cervical anterior translation (causing a "forward head"). An additional complicating postural factor can be the alignment of the scapula on the thoracic cage – when the shoulder is "rolled forward" (protracted). Correction of these chronic alignment faults will significantly reduce the biomechanical stress on muscular support for the shoulder.

And now we understand that even the coordination of the lower extremities during gait is a critical aspect of shoulder function.5 At the same time gravity and ground reaction forces are affecting the legs and feet, the torso and shoulder also are responding. With each step, the scapula reacts to opposite-leg loading by tipping anteriorly in the sagittal plane, rotating upward in the frontal plane, and gliding around the rib cage in the transverse plane (protraction). This reaction at the shoulder produces the appearance of a hunched and forward-rounded shoulder, and can be described as "shoulder pronation."

The biomechanical and neurological processes that link shoulder pronation to lower extremity pronation on the opposite sides help us understand some of our previous treatment failures.

The Importance of Gait

As the leg is loaded in gait, trunk side-bending occurs to the loading leg. The lumbar spine rotates away from the loaded leg and a balancing rotation occurs in the thoracic spine to the same side as the loading leg. The scapula then slides forward on the rib cage into the protracted position. It is the eccentric loading of the periscapular muscles that controls this scapular reaction, and the shoulder is now ready to retract with efficiency. The entire relationship of the shoulder, rib cage and thoracic spine is driven by the cross-crawl neurological reaction to gait.

There are also common hip motions that can function as "cheaters" for the shoulder. This occurs when the shoulder muscles are weak, fatigued or overloaded. The strength of the large muscle mass around the hip can substitute and alter the mechanics to the weakened shoulder muscles’ benefit.

For instance, transverse plane activity, such as external rotation of the shoulder, is assisted by opposite-hip internal and external rotation. This means excessive pronation on the opposite leg can interfere significantly with normalization of the neuromuscular balance between the internal and external rotator muscles of the shoulder. To address this, corrective orthotics that limit pronation are often needed to fully rehabilitate shoulder injuries and chronic symptoms.

Address the Entire Musculoskeletal System

This insight allows us to understand why it is so important to develop a shoulder rehab program that addresses the entire musculoskeletal system, including any excessive or asymmetrical foot pronation. An appropriate and progressive rehab program should be started early in the treatment of patients with shoulder sprain and strain injuries. Simple, isotonic rehab techniques are available, none of which requires expensive equipment or great time commitments. A closely monitored home exercise program is recommended, since this allows you to provide cost-efficient, yet effective and specific rehabilitation care.

The most important aspect is to recognize and address the biomechanical alignment problems and postural factors that are frequently associated with shoulder injuries. This entails screening the patient for forward-head and flexed (kyphotic) torso postures. In addition, protracted (forward) shoulders change the angle of the scapula and compress the rotator cuff further. Pronation of the opposite foot and ankle will interfere with full rehabilitation.

Failure to recognize these complicating factors will result in a patient with recurring shoulder complaints. When the shoulder girdle is properly aligned on the torso,and the gait mechanism is functioning properly, the complex mechanism of the shoulder can be optimally rehabilitated.

References

- Tzannes A, Murrell GA. Clinical examination of the unstable shoulder. Sports Med, 2002;32(7):447-457.

- Roy S, Irvin R. Sports medicine: Prevention, Evaluation, Management, and Rehabilitation. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1983; p. 195.

- Hertling D, Kessler RM. Management of Common Musculoskeletal Disorders, 4th Edition. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 2006; p. 177.

- Hammer WI. Functional Soft Tissue Examination and Treatment by Manual Methods. Gaithersburg: Aspen Pubs, 1991; p. 31.

- Walendzak D. Lower extremity theory enhances shoulder rehabilitation. Biomechanics,1998 Oct:45-51.