It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

Running Form: Should a Heel-First Strike Pattern Be Discouraged?

Editor's note: This is the first article in a series relevant to your patients who run.

Despite the fact that the overwhelming majority of slow runners instinctively strike the ground with their heels, there is a growing trend among running experts to have recreational runners strike the ground with their mid- or forefoot. Proponents of the more forward contact point suggest that a mid- or forefoot strike pattern is more natural because experienced, lifelong barefoot runners immediately switch from heel to midfoot strike patterns when transitioning from walking to running.

Strike Patterns and Injury Potential

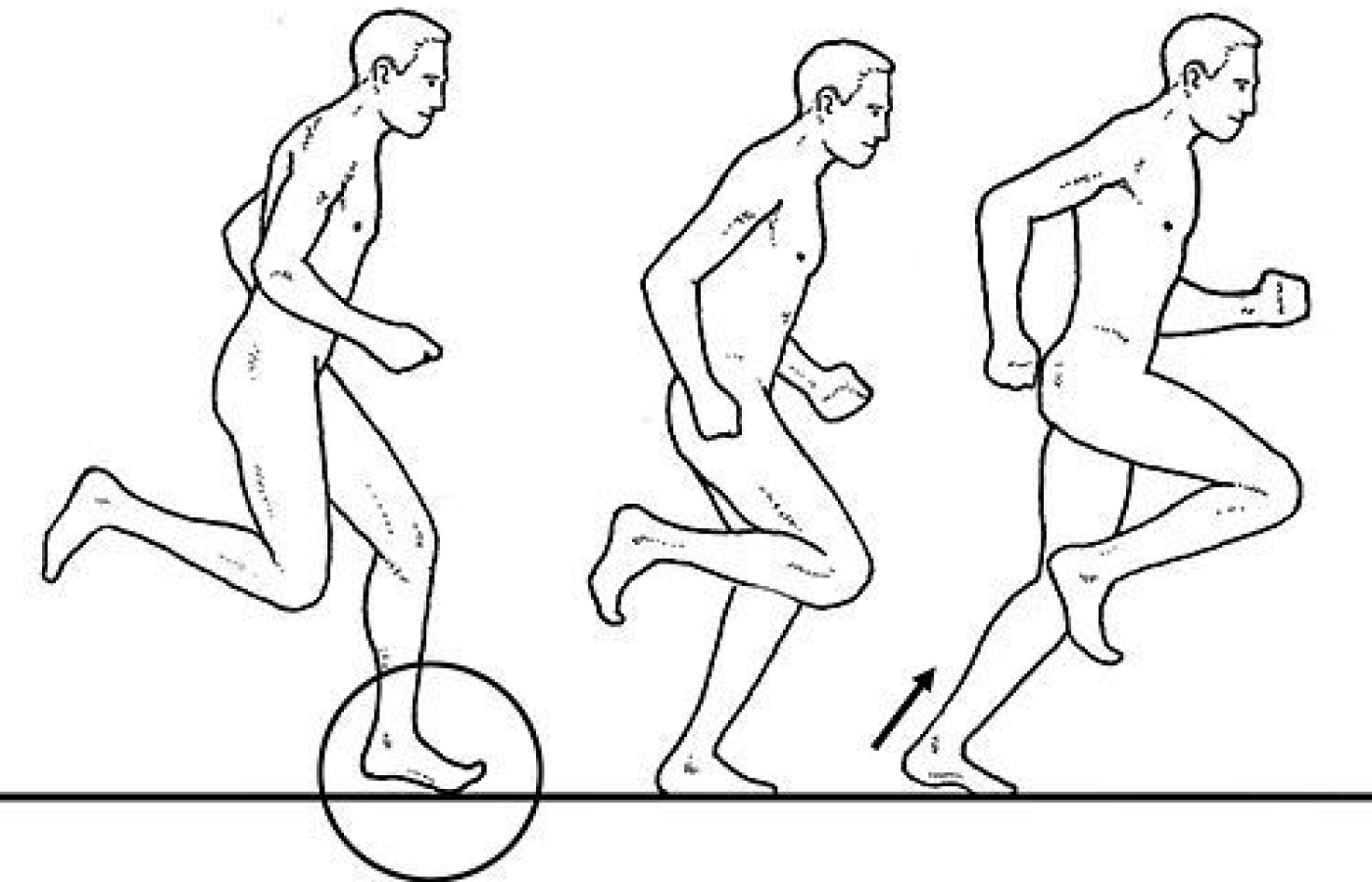

The switch to a more forward contact point is theorized to improve shock absorption (lessening our potential for injury) and en-hance the storage and return of energy in our tendons (making us faster and more efficient). (See figure) However, although appealing, the notion that switch-ing to a mid- or forefoot contact point will lessen the potential for injury and improve efficiency is simply not true. Regarding injury, epidemio-logical studies evaluating more than 1,600 recre-ational runners conclude there is no difference in the incidence of running-related injuries between rearfoot and forefoot strikers.1

Advocates of midfoot strike patterns cite a frequently referenced study showing that runners making initial contact at the midfoot have 50 percent reduced rate of injuries.2 The problem with this study is that the 16 runners involved were all Division I college runners who self-selected a midfoot strike pattern. While self-selecting a midfoot strike pattern is fine and is often the sign of a high-level athlete, it's the conversion of a rec-reational heel strike runner into a midfoot strike runner that is problematic.

In my experience, the world's fastest runners who self-select midfoot strike patterns tend to be biomechanically per-fect, with well-aligned limbs, wide forefeet, and neutral medial arches. Over the past 30 years, I've noticed that flat-footed runners who attempt to transition to forefoot strike patterns tend to get inner foot and ankle injuries (such as plantar fasciitis and Achilles tendinitis), while high-arched runners attempting to transition to a more forward contact point frequently suffer sprained ankles and metatarsal stress fractures.

In a detailed study evaluating the biomechan-ics of habitual heel and forefoot strike runners, researchers from the University of Massachusetts demonstrated that runners who strike the ground with their forefeet absorb more force at the ankle and less at the knee.3 The opposite is true for heel strikers, in that they have reduced mus-cular strain at the ankle with increased strain at the knee.

This is consistent with several studies confirming that the choice of a heel or midfoot strike pattern does not alter overall force present during the contact period; it just transfers the force to other joints and muscles. Midfoot strikers absorb the force in their arches and calves, while heel strikers absorb more force with their knees. This explains the much higher prevalence of Achilles and plantar fascial injuries in mid- and forefoot strikers, and the higher prevalence of knee pain in heel strikers.

This research proves that choosing a specific contact point does not alter overall force; it just changes the location where the force is absorbed. This is the biome-chanical version of "nobody rides for free."

The research suggesting midfoot strike patterns are more efficient than rearfoot strike patterns is even more spurious than the research suggesting a forward contact point reduces inju-ry rates. In an important paper published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, scientists cal-culated joint torque, mechanical work performed, and muscle activity associated with altering initial contact points at various speeds of walking and running.4 The results of this study con-firmed that running with a mid- or forefoot contact provided no clear metabolic advantage over heel-first strike pattern.

In contrast, walking with a heel-first strike pattern reduced the metabolic cost of walking by a surprising 53 percent. That's a huge difference in efficiency and explains why almost all slow joggers (who often run just a little faster than walking pace) make initial ground contact with their heel. While some elite runners are efficient while landing on the forefeet, the overwhelming majority of slower runners are more efficient with a heel-first strike pattern.

Heel Strike and Metabolic Efficiency

The big question is, since the world's fastest runners often strike the ground with their forefeet, while slow runners strike with their heels, at ex-actly what speed do you lose the metabolic effi-ciency associated with heel strike? In a computer-simulated study evaluating efficiency, researchers from the University of Massachusetts showed that while running at a 7:36 minutes/mile pace, heel striking was approximately 6 percent more efficient than mid- or forefoot striking.5 Some experts believe that the 6-minute-mile pace is the transi-tion point at which there is no difference in econ-omy between heel and midfoot strike patterns.

Given the clear metabolic advantage associat-ed with heel striking at all but the fastest running speeds, it's not surprising that when asked to rate comfort between heel and midfoot strike patterns, recreational runners state that a rearfoot strike pattern is significantly more comfortable.6 Im-proved efficiency also explains why approximate-ly 35 percent of recreational runners transitioning into minimalist footwear continue to strike the ground with their heels, despite the amplified impact forc-es: Heel striking is too efficient to give up.7

Clinical Pearls

The bottom line is that before you have a runner convert from a rearfoot strike to a midfoot strike, make sure it's clinically justified. Because midfoot strike patterns significantly reduce stress on the knee, they should be considered for all runners with recurrent retropatellar pain. This is especially true for faster runners with neutral arches, wide forefeet, and flexible Achilles tendons. Conversely, slower runners with a history of Achilles, forefoot and/or plantar fascial injuries should almost always make initial contact along the lateral heel, because contrary to what many running experts say, striking the ground heel first is safe and efficient.

References

- Kleindienst F, Campe S, Graf E, et al. Dif-ferences between fore- and rearfoot strike running patterns based on kinetics and kine-matics. XXV ISBS Symposium 2007, Ouro Preto, Brazil.

- Daoud A, Geissler G, Wang F, Saretsky J, Daoud Y, Lieberman D. Foot strike and injury rates in endurance runners: a ret-rospective study. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2012;Jul;44(7):1325-34.

- Hamill J, Allison H. Derrick G, et al. Low-er extremity joint stiffness characteristics during running with different footfall patterns. Euro J Sports Sci, Oct 15, 2012.

- Cunningham C, Schilling N, Anders C, et al. The influence of foot posture on the cost of transport in humans. J Exper Biol, 2010;213:790-797.

- Miller R, Russell E, Gruber A, et al. Foot-strike pattern selection to minimize muscle energy expenditure during running: a com-puter simulation study. Annual meeting of the American Society of Biomechanics, State College, Pa., 2009.

- Delgado T, Kubera-Shelton E, Robb R, et al. Effects of foot strike on low back posture, shock attenuation, and comfort in running. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2013;4:490-6.

- Goss D, Lewek M, Yu B, et al. Accuracy of self-reported foot strike patterns and loading rates associated with traditional and minimalist running shoes. Human Movement Science Research Symposium, 2012; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.