It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

A Review of Abdominal Calcifications

Although plain-film radiographs are commonly acquired by the chiropractor, the abdominal plain film, also known as the abdominal scout or kidney, ureter, bladder (KUB) study, is not typically considered. In actuality, the plain-film abdomen study is very similar to the frontal lumbar spine study routinely performed in chiropractic offices. Although there is a difference in the collimation and the factoring of the lumbar study, essentially all the anatomy visualized on the abdominal plain film can be identified on the abdomen study as well.

To begin, there are two factors that must be considered to assist the interpreter in forming a differential and ultimately a definitive diagnosis. The first factor is the type of calcification; the second factor is the location of the calcification.

Types of Calcifications

Four patterns of calcification can be identified within the abdomen. Each type will present with specific characteristics on X-ray. These calcification patterns assist the interpreter in establishing the differential, and at times, the final diagnosis. The four patterns are concretions, conduit wall calcification, cyst wall calcification and solid mass calcification.1,2,3

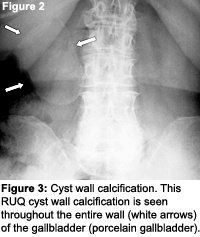

Cyst wall calcification. When the wall of a fluid-filled cyst or hollow organ calcifies, it becomes a cyst wall calcification. An aneurysm of a vessel would actually be included here and not in the conduit wall category. To differentiate between cyst and conduit wall calcification, it is important to establish that the diameter of the calcification is greater than that of the normal conduit. If this is the case, it gets placed in the cyst wall category.1,2 The radiographic pattern of a cyst wall calcification is a curvilinear or arc-like calcification (Figure 3). Structures that may present with cyst wall calcification are aneurysms, the gallbladder and cysts found within solid organs.1,2,3

Anatomic Location

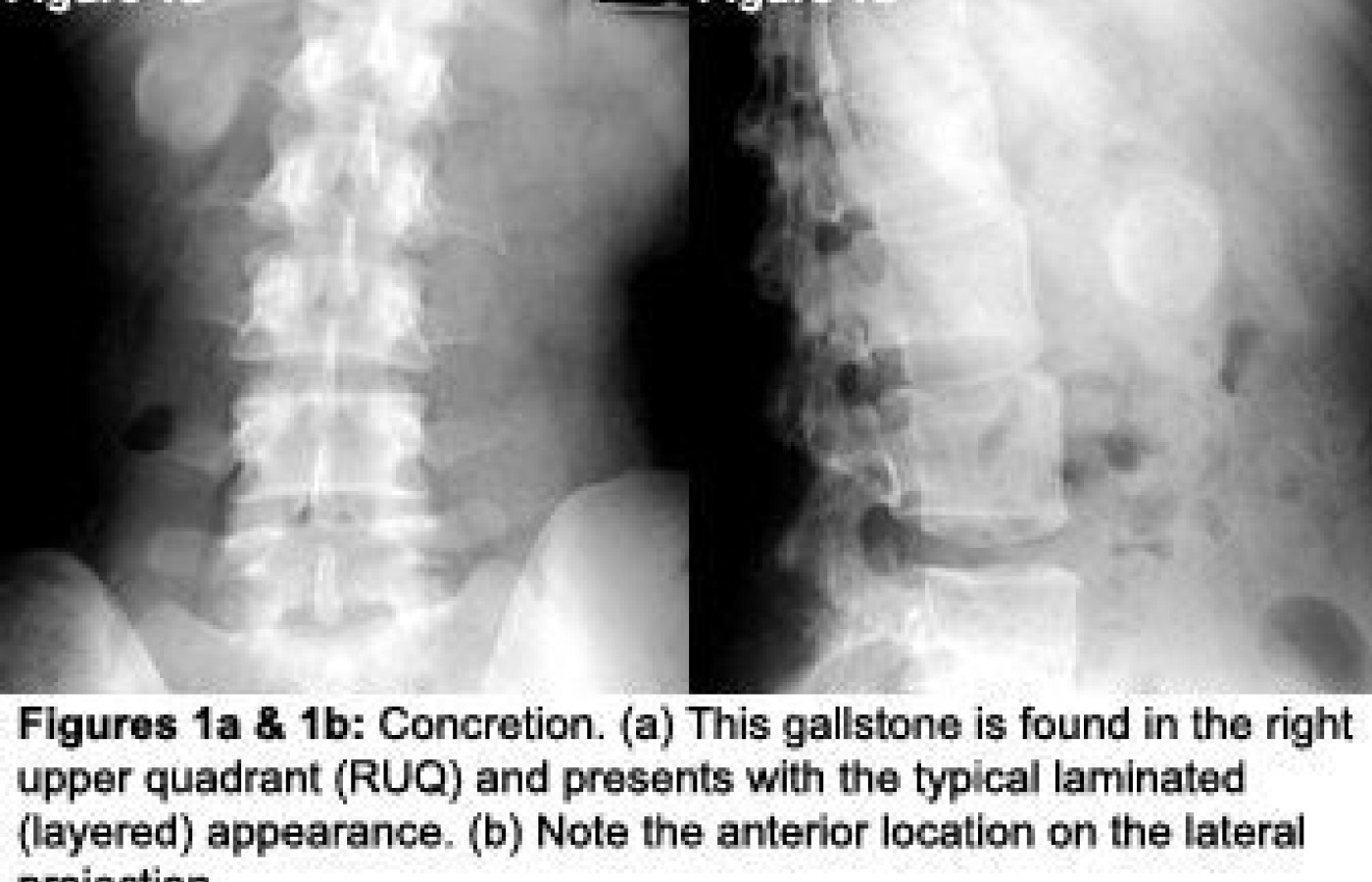

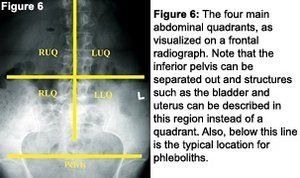

For evaluation purposes, it is best to break the abdomen into four quadrants (Figure 6): right upper quadrant (RUQ), left upper quadrant (LUQ), right lower quadrant (RLQ) and left lower quadrant (LLQ). In addition to the quadrants, the lateral projection will assist in identifying if the object is in the anterior (typically intraperitoneal) or posterior (typically retroperitoneal) location.

The table below5 demonstrates which calcification pattern typically is seen in each respective anatomical structure and where those structures are positioned in the abdomen. A commonly found calcification within the pelvis is the phlebolith. A phlebolith is a stone that forms within the pelvic veins and will present as a concretion in the lower half of the pelvic inlet. It represents an incidental finding and is often not even noted on radiology reports.

| Table 1 | |||

| Quadrant | Peritoneal Location | Anatomic Structure | Calcification Pattern |

| RUQ | Anterior | Liver | Cyst wall/Mass |

| RUQ | Anterior | Gallbladder | Concretion |

| LUQ (most)/RUQ (some) | Posterior (most) | Pancreas | Mass |

| RUQ/LUQ | Posterior | Adrenal Glands | Cyst wall/Mass |

| RUQ/LUQ | Posterior | Kidney/Ureter | Cyst wall/Concretion |

| LUQ | Anterior | Spleen | Cyst wall/Mass |

| RLQ | Anterior | Appendix | Concretion |

| RLQ/LLQ/Pelvis | Anterior (most) | Ureter/Bladder | Concretion |

| RLQ/LLQ/Pelvis | Posterior | Ovary | Cyst wall/Mass |

| RLQ/LLQ/Pelvis | Posterior (most) | Uterus | Cyst wall/Mass |

| LUQ/RLQ/LLQ | Anterior | Mesentery | Cyst wall/ Mass |

| RLQ/LLQ/Pelvis | Anterior | Small Pelvic Vessels | Conduit wall |

Conclusion

References

- Bassano J. Abdominal calcifications and imaging decision making: a topic review. J Chiro Medicine 2006; 5(1):43-52.

- Baker SR. The Abdominal Plain Film, 1st edition. Connecticut: Appleton & Lange; 1990.

- Marchiori D. Clinical Imaging With Skeletal, Chest and Abdomen Pattern Differentials, 1st edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 1999.

- The American Heritage Dictionary, 2nd college edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. 1985. Conduit; p. 307.

- Netter FH. Atlas of Human Anatomy, 1st edition. New Jersey: CIBA-GEIGY; 1989.