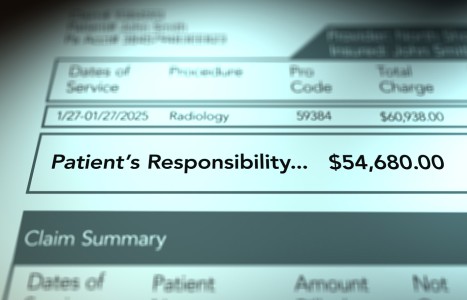

Recent laws in New Jersey and California represent a disturbing trend that will negatively impact a practice’s ability to collect monies from patients, as well as expose them to significant penalties if the practice does not follow the mandatory guidelines to a T. Please be aware that a similar law may be coming to your state. The time to act is before the law is passed.

Compliance Programs: A Silk Purse or a Sow's Ear? Part 1 of 2

Health care practitioners have been hearing more and more in recent years about a thing called "compliance." As it's used today, the term generally refers to compliance with the rules and regulations applicable to billing insurance companies and Medicare. The rare health care practice that has truly confronted compliance is relatively safe from allegations of insurance or Medicare fraud; one that works only intermittently on compliance, or not at all, is far more likely to be subjected to investigation and to accusations of fraudulent conduct.

To help practitioners navigate the relatively dangerous waters of compliance, the Office of the Inspector General has recommended all practices adopt a formal compliance plan designed to decrease the incidence of inadvertently fraudulent billing practices. In response, several companies have compiled and sell "compliance plans," which generally are promoted to offer protection from allegations of fraud. Unfortunately, not all of these products deliver much in the way of protection.

There is much truth in the adage, "You can't make a silk purse from a sow's ear." For example, if the only product you have to sell is pain medication, your patients are not going to be a particularly healthy lot. Drugs that mask pain might make the patient "feel better," but they do nothing to cure the underlying cause of the pain and thus do nothing to promote the patient's health. In fact, because they mask the body's natural mechanism for protecting an injured body part and thus preventing further damage, pain medications probably do more to exacerbate unhealthy conditions than to promote healthy ones.

The same adage applies equally to the choice among the compliance plans available on the market today. Health care providers need to become aware that many of the plans on the market do not provide full protection from allegations of insurance or Medicare fraud. The astute provider will learn to distinguish between those plans designed to provide maximum protection (the silk purse) and those that migh create the opposite effect (the sow's ear).

A Hostile Environment

Most people are aware that the health care service industry in this country is in a state of crisis. Rising health care costs, time-consuming rules concerning which providers can be used within the confines of any health plan, and staggering recoveries by plaintiffs in malpractice claims all bear witness to the fact that our health care system is breaking down.

What often is missed in the media barrage concerning these issues is the fact that most health care professionals in this society are operating in a hostile environment. Health care providers interviewed for this article claim it gets more difficult each year to get paid through the various government and health insurance programs, such as Medicare and Blue Cross. In fact, criminal investigations and governmental audits of health care practitioners are on the rise. The insurance companies are not far behind, as their criminal investigations and audit functions also are growing steadily.

Professionals who deal with personnel from the insurance companies' "special investigation units" report that the investigators appear to be "out for blood." Such investigations do not seem designed to lead to mere adjustments of errors made by health care providers, but rather to the incarceration or bankruptcy of those providers. The investigators normally are examining reimbursements claimed five or 10 years ago. Yet when excess reimbursements are found, they generally must be repaid within 60 days of their discovery.

Common Problems Lead to Fraud

Potential excess reimbursements arise from any number of common situations, one or more of which are apt to plague the records of any provider not actively watching for them. "Upcoding" is one of the most common errors. This means the provider claimed a reimbursement code for a procedure that pays at a higher rate than the procedure actually performed on the patient. This can sometimes reflect an actual intention to defraud the carrier and collect more from them than their rules allow. However, in our experience this is the least likely scenario. Upcoding more frequently arises through simple optimism on the part of coding personnel, or when coding personnel are not kept current with changes in the various codes applicable to the practice. Unfortunately, investigators likely are to ascribe many such "errors" to a fraudulent intent.

Upcoding is only one of the practices that can result in difficulty for the provider. Similar problems stem from billing the carrier for services that actually were not delivered to the patient. Sometimes a provider will collect both a cash payment and an insurance reimbursement for the identical service. Sometimes a provider simply might fail to prepare and file adequate documentation to support the services actually delivered to the patient and billed out for reimbursement. Similarly, if a provider delivers medically unnecessary services, or simply is unable to prove they were medically necessary, they likely are to receive no reimbursement and to raise a "red flag" as well.

Editor's note: Part 2 of this article will appear in the Dec. 3, 2006 issue of DC.