It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

Show Me Chiropractic (Part 2 of 2)

Editor's note: Part 1 of this article appeared in the Feb. 26 issue.

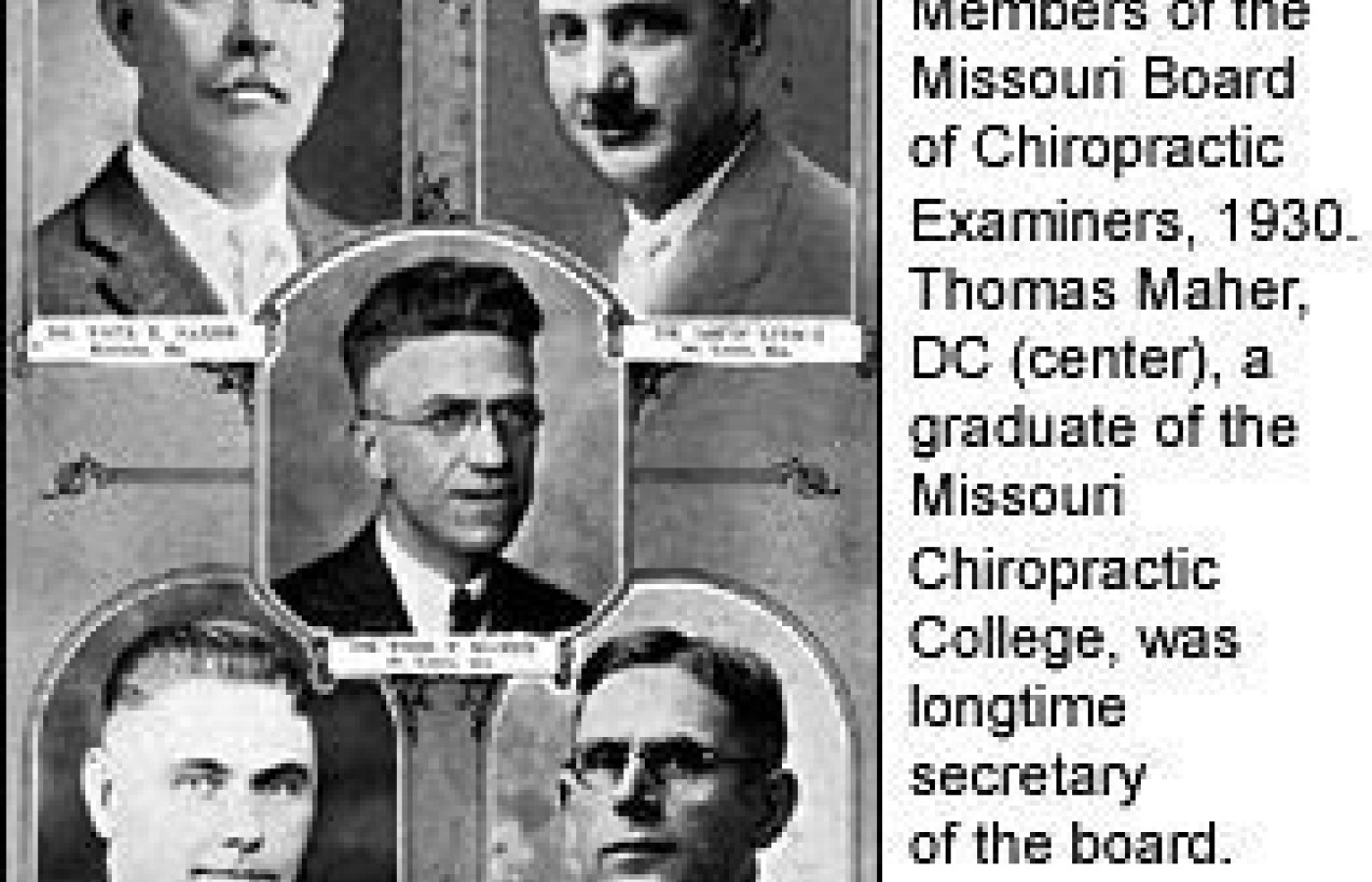

With the passage of the chiropractic statute in Missouri in 1927, the Show Me State became a target for basic science legislation. However, this never came to pass, owing at least in part to the efforts of Dr. Cleveland Sr. Carl Jr. recalled accompanying his father to a meeting with political boss Tom Pendergast, at which the elder Cleveland suggested that requiring a chiropractor to pass an exam administered by the medical faculty was analogous to asking a Catholic priest to take a test from a rabbi before saying mass. Pendergast, a Catholic, readily accepted this reasoning, and blocked repeated efforts by the medical lobby to enact a basic science bill.

Although Missouri never enacted basic science legislation, Kansas City was the site for the seminal meeting in 1926 of the International Congress of Chiropractic Examining Boards (ICCEB), whose formation was prompted in part by the threat of basic science laws. Established at the urging of Harry Gallaher, DC, a member of the Oklahoma Board of Chiropractic Examiners, the ICCEB would be transformed in 1934 into the Council of State Chiropractic Examining Boards, and later renamed the Federation of Chiropractic Licensing Boards (FCLB).

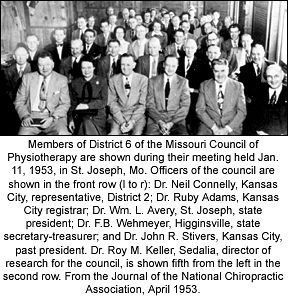

Dr. Ruby Adams, Kansas City registrar; Dr. Wm. L. Avery, St. Joseph, state president; Dr. F.B. Wehmeyer, Higginsville, state secretary-treasurer; and Dr. John R. Stivers, Kansas City, past president. Dr. Roy M. Keller, Sedalia, director of research for the council, is shown fifth from the left in the second row. From the Journal of the National Chiropractic Association, April 1953.

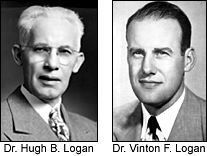

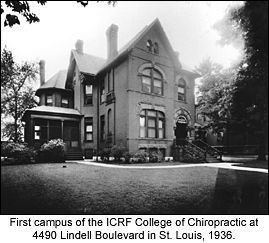

In the early 1930s, two graduates of the Universal Chiropractic College commenced nationwide instruction in a new method of chiropractic they termed "Basic Technique" (BT). Dr. Hugh B. Logan and his son, Dr. Vinton Logan, inspired the formation of the International Chiropractic Research Foundation (ICRF) in upstate New York. The ICRF was committed to studying and disseminating BT as a scientific revolution in the profession. When "H.B." consented to the idea of forming a chiropractic school to train "basic technicians," St. Louis was chosen as the home for the new institution. Originally known as the ICRF College of Chiropractic (today's Logan College of Chiropractic), the school opened its doors to students in September 1935 with a curriculum of 36 months (four years of nine months each, with summers off). The ICRF College was probably only the second school (after the Metropolitan Chiropractic College of Cleveland in 1933) to offer training of this duration for chiropractors. The school's first campus, a renovated home on Lindell Boulevard, soon proved inadequate, and a second facility consisting of 17 acres in Normandy, a St. Louis suburb, was purchased by H.B. in 1937.

The ICRF and the Logans parted company in 1937. Following the elder Dr. Logan's passing in 1944, the college wandered in and out of affiliation with the National Chiropractic Association's (NCA's) Council on Education (today's CCE). Personal animosities erupted between John J. Nugent, DC, director of education for the NCA, and the college's new president, Dr. Vinton Logan. Nugent, whom B.J. Palmer would label the "anti-Christ of chiropractic," received especially unpleasant receptions in Missouri, where the state journal editorialized about the "dark cloud of "Nugentism" descending upon the state. Nonetheless, the Clevelands more than once came to the NCA leader's defense when he was misquoted.

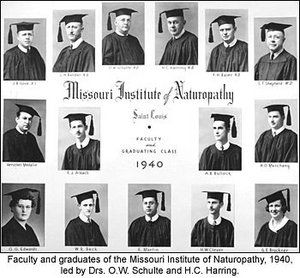

Despite the straight chiropractic orientation of two of the three chiropractic schools in the state during the 1950s, a number of chiropractors evidenced sustained interest in broad-scope methods. Missouri Chiropractic College provided instruction in physiotherapeutics and had organized a sister institution for instruction in naturopathy. A state branch of the NCA's Council on Physiotherapy was organized in Missouri. Straights and mixers vied with one another over scope-of-practice issues for years.

This brief review of the early days of chiropractic in the Show Me State cannot do justice to the rich detail or significance of Missouri's contribution to the profession's saga. But hopefully, it has suggested that much information is indeed available, and that the story needs to be told.

Joseph Keating Jr., PhD

Phoenix, Arizona

jckeating@aol.com