It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

At the 100-Year Mark: Western States Chiropractic College

This year marks the 100th anniversary of another chiropractic school, probably the second oldest (following Palmer College) surviving educational institution in the profession. Today's Western States Chiropractic College (WSCC) is the product of several mergers and reinventions during the first four decades of the 20th century. The institution was a pioneer in chiropractic education in several respects, and has been a torchbearer for broad-scope practice in the profession. This brief review of the college's saga focuses on those earliest years.

Founding Dates of Several of the Longest Surviving (or Merged) Chiropractic Schools:

| 1896: | Palmer School of Magnetic Cure (now Palmer Chiropractic University) |

| 1904: | Marsh School & Cure (now Western States Chiropractic College) |

| 1906: | National School of Chiropractic (now National University of Health Sciences) |

| 1906: | Carver Chiropractic College (merged with Logan College of Chiropractic) |

| 1908: | The Chiropractic College of San Antonio (now Texas Chiropractic College) |

| 1910: | Universal Chiropractic College (merged with Lincoln Chiropractic College, which merged with National College of Chiropractic) |

| 1911: | Ratledge System of Chiropractic Schools, Los Angeles (now Cleveland Chiropractic College of Los Angeles) |

| 1911: | Los Angeles College of Chiropractic (now Southern California University of Health Sciences) |

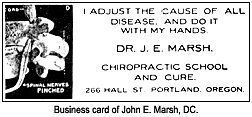

The WSCC's earliest ancestor, and probably the first chiropractic training facility in Oregon, was the Marsh Chiropractic School and Cure, which opened its doors at "Southeast Fifth and Hall" in Portland.1 John E. Marsh, DC, a 1904 graduate of the Minnesota School and Cure (alternately remembered as the Brainiard School and as Dr. Lynch's School of the Brainiard College), probably the same institution from which Almeda Haldeman (grandmother of Dr. Scott Haldeman) received her chiropractic degree.2 Dr. Marsh may also have studied at the Palmer School of Chiropractic.3

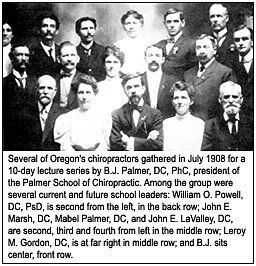

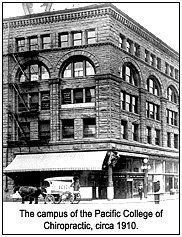

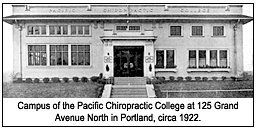

Little is known of the early days at the Marsh School; its operations may have involved little more than an apprenticeship. However, by 1907, the school had relocated to the Fliedner Building in Portland. At this time also, the school seems to have assumed its new name: the Pacific Chiropractic College (PCC).1 Dr. Marsh and one of his first graduates, William O. Powell, DC, operated the "Chiropractic Health Home" in Dayton, Oregon,4 and secured "an exemption to the new Oregon medical bill, originally written to completely ban the chiropractic profession."1

In 1909, PCC was reportedly chartered as a nonprofit corporation (one of the earliest in the profession), and Dr. Powell became its president. He was joined in the venture by faculty and administrators Newton J. Baxter, DDS, DC; A.N. Briggs, DC; and Minnetta H. Baxter, DC (wife of Newton).6

PCC offered a curriculum of two terms of four months; each term involved tuition of $150 and special lectures in "Psychology, Obstetrics, Surgical Emergencies, First Aid to the Injured, and Care of the Teeth and Mouth." Oral hygiene would presumably have been taught by dentist-chiropractor Baxter, and psychology course-work probably reflected the interests of Dr. Powell, who listed his credentials as "DC" and "PsD." (The latter possibly stood for "doctor of psychology.") For those interested in training in "the Higher Branches of Life Philosophy. The laws of Physical and Psychical Expression, and the Philosophy of Ease,"7 a "master of ease" degree was also available. The college's emblem reflects this interest in a philosophy and science of "ease." We may speculate that this concept was the opposite of "dis-ease."

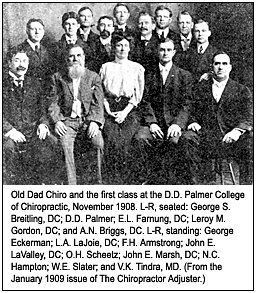

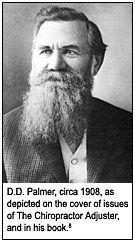

Instruction in obstetrics and minor surgery for chiropractors was not new to Oregon. D.D. Palmer had relocated his "Fountain Head School" from Oklahoma City to Portland late in 1908, at which time the institution was identified as the D.D. Palmer College of Chiropractic. "Old Dad Chiro's" curriculum offered instruction in obstetrics and minor surgery, apparently in keeping with Palmer's charge:

"A chiropractor should be able to care for any condition which may arise in the families under his care, the same as a physician; this we intend to make possible in a two-year's course."8

Palmer's relocation may have been prompted, in part, by his anticipation that son B.J. Palmer, DC, might be contemplating the opening of a branch campus of the original Davenport school. Father and son had parted company in 1906, and were conducting an unpleasant public feud over priority in the profession. The father of chiropractic insisted he was the "fountain head" of the profession, the source of all original ideas in the science and philosophy of chiropractic. The two Palmers also feuded over who merited the appellation "discoverer" of chiropractic, and about various theoretical and technical points bearing on subluxation and adjustment.9

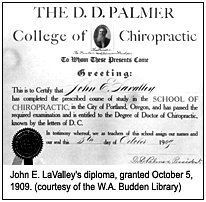

D.D. Palmer's Portland school proposed a two-year curriculum with a competitive tuition of $250 per year (in contrast to the $500 tuition he had originally charged in Davenport for a few months of apprenticeship). However, he may not have completed the promised course offering in Portland, and at least some students received their diplomas after the first year of instruction.5 Palmer's partners in the Portland venture included Leroy Gordon, DC, and John E. LaValley, DC, each of whom, in turn, served as "manager" of the college.

The elder Palmer's stay in Portland, which lasted until late 1910 or early 1911,10 was a productive period for the father of the profession. It was here that he turned out perhaps as many as eight issues of his new periodical, The Chiropractor Adjuster (at least six of which have survived). Much of the contents of this magazine would be re-offered in the pages of Palmer's classic text, The Science, Art & Philosophy of Chiropractic: The Chiropractor's Adjuster.8

It was in Portland that Palmer fully developed his third and final theory of chiropractic,11,12 wherein he rejected his earlier notion, bone-pinches-nerve, in favor of the idea of the skeleton as a regulator of neural tension.13 The founder had decided by this time that nerves were never pinched within the intervertebral foramina, but rather, might be stretched too taut or slackened by misalignment of joints anywhere in the body. An often-truncated quote was offered in support of the idea that nerve-pinching was irrelevant to the pathology he supposed he corrected; the correction of the joints of foot and toes involved no nerves passing between bones: "I have never felt it beneath my dignity to do anything to relieve human suffering. The relief given bunions and corns by adjusting is proof positive that subluxated joints do cause disease."8

With the introduction of this third iteration of chiropractic theory, Palmer commenced to criticize all who neglected to reorient their ideas in conformity with the new hypotheses. Coming in for focused scorn was rival Portland school leader William Powell. Palmer's relationship with his partner/manager also turned sour sometime in 1909, but since Dr. LaValley had the greater financial investment in the school, D.D. departed Portland, bound for Los Angeles, where he would teach on the faculty of the Ratledge Chiropractic College (today's Cleveland College of Los Angeles).

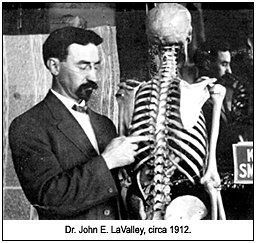

LaValley and two former students renamed the school as the Oregon Peerless College of Chiropractic-Neuropathy. They offered a 12-month curriculum leading to a combined degree designated "DC-N," but the focus of the training remained on subluxation and adjustment. Neuropathy, which combined chiropractic concepts with various other forms of drugless healing, was a term also employed by another D.D. Palmer rival and former student, Andrew P. Davis, MD, DO, DC,14 who was residing in Oregon in 1909. What connection or communication there may have been between Drs. Davis and LaValley is not known.

LaValley claimed that his school was the first in Oregon to provide anatomical instruction by dissection. However, since dissection was an instructional offering D.D. Palmer had also promised, it is possible that LaValley's comments refer to the earlier iteration of the Oregon Peerless College. The school may have continued to operate only until its first class graduated in 1912, but there is some uncertainty about this.5 The generally accepted version is that LaValley persuaded a reluctant Dr. Powell to merge PCC with Oregon Peerless College in 1913.1 LaValley became an instructor at the merged institution, which kept the Pacific College title. He apparently did not remain on the faculty for very long.

Trustees, Administrators, Faculty and Courses Taught at the Pacific Chiropractic College, 1915:*5

- William O. Powell, PsD, DC, trustee, president, director of clinics, principles & practice of chiropractic

- A.N. Briggs, DC, trustee

- J.A. Goode, DC, trustee, department of physiology

- H.E. Kehres, A.B., dean of the college, anatomy, gynecology, obstetrics, physical diagnosis, minor and operative surgery

- Lester E. Couch, AB, LLB, Chiropractice Jurisprudence

- Two positions were vacant: laboratory director and instructor in EENT.

The PCC curriculum had grown to four terms by 1915.1 By then, the school was located in Portland's Commonwealth Building. A well-structured curriculum and school catalog were in evidence by this time, and the student clinic provided free services to the public, which presumably yielded an adequate flow of patients for training. President Powell was replaced by Dr. H.E. Kehres in 1914; Kehres may have been an allopathic physician. The school was purchased by one of its alumni, Oscar W. Elliott, DC, PhC, MC, in 1915; the purchase implies that the PCC was no longer nonprofit, although corporate records would need to be checked to verify this. Dr. Elliott may also have been an allopath, although this is not certain.1

The new president moved the school to new quarters, first at Seventh Street and Yamhill, and subsequently to 125 Grand Avenue North. The curriculum had grown to 3,400 hours by 1919 (an exceptionally long duration for chiropractic education in that era and 1,000 hours in excess of the minimum required for licensure in Oregon at that time). However, given the tendency of many chiropractic schools at that time to inflate curricular offering by defining hours as something less than 60 minutes, the actual duration of the curriculum may be suspect. By 1922, PCC claimed a faculty of 12, and offered several degrees: DC, PhC (Philosopher of Chiropractic), and MC (Master of Chiropractic).

| Curricular Subjects and Hours, Pacific Chiropractic College, 1922*5 | |

Subject | Hours |

| Anatomy | 150 |

| Histology | 135 |

| Physiology | 260 |

| Chiropractic Theory and Practice | 1,000 |

| Chemistry | 120 |

| Pathology | 270 |

| Gynecology | 105 |

| Hygiene and Sanitation | 125 |

| Obstetrics | 195 |

| Diagnosis | 340 |

| Toxicology | 40 |

| *PCC's catalogue indicated that these were the minimum 2,400 hours required for licensure in Oregon, and that the "standard" three-year curriculum exceeded these by 1,500 hours; the above hours actually total 3,140 hours. | |

Elliott affiliated the PCC with the broad-scope-tolerant American Chiropractic Association of the 1920s, a national protective society which competed with B.J. Palmer's Universal Chiropractors' Association for members.15 In 1925, he was active in successful legislative efforts to raise the educational requirements for licensure in Oregon to 3,200 hours. Oscar Elliott passed away in December 1926, and the school came under the supervision of his wife, Dr. Lenore Elliott (degree unknown), and N.S. Checkos, MD (who served as dean).1,16

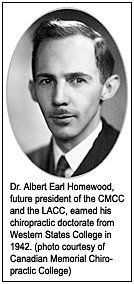

PCC entered a new phase in January 1929, when the college was purchased for $20,000 by the former dean of the National College of Chiropractic in Chicago, William Alfred Budden, DC,ND.1,17 The timing was terrible, for the U.S. stock market crash and the onset of the Great Depression were only nine months away. Dr. Budden would struggle for years to keep the school afloat, eventually re-chartering the institution as the nonprofit Western States College, including instruction leading to degrees in chiropractic and naturopathy. During his tenure at the reins of the institution (he died "in the saddle" in 1954), the Western States College, School of Chiropractic and School of Naturopathy, would exert a profound influence on the course of the profession, both through Budden's activities within the National Chiropractic Associa-tion's Council on Education (today's CCE), and by way of the several exceptional doctors he trained.

The length and breadth of the Western States experience has yet to be told, but merits intensive scrutiny for several reasons. These include the leadership role its faculty and alumni have played in chiropractic affairs, the exceptionally broad scope of practice that it has fostered over the years, and for the perseverance that this small school has shown in the face of adversity. But these are tales for another time.

Happy birthday to Western States.

References

- Ritter, Judith C. The roots of Western States Chiropractic College 1904-1932. Chiropractic History 1991 (Dec);11(2):18-24.

- Haldeman, Scott. Almeda Haldeman, Canada's first chiropractor: pioneering the prairie provinces, 1907-1917. Chiropractic History 1983; 3:64-7.

- Palmer, B.J. Does Willard Carver tell the truth? Fountain Head News, 1919 [A.C. 25] (Nov. 22, Saturday); 9(10):1-2.

- Chiropractic: A Book of New Ideas About Your Disease. Pamphlet, 1905 (Palmer College Archives #B.J., RZ2 44.C445 1905).

- Keating, Joseph C. Early chiropractic education in Oregon. Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association 2002 (Mar);46(1):39-60.

- Announcement. Bulletin of the Pacific College of Chiropractic Inc. 1910 (May);1(1):2-3.

- Academic course. Bulletin of the Pacific College of Chiropractic Inc. 1910 (May);1(1):13-4.

- Palmer DD. The Chiropractor's Adjuster: The Science, Art and Philosophy of Chiropractic. Portland Oregon: Portland Printing House, 1910.

- Keating, Joseph C. B.J. of Davenport: The Early Years of Chiropractic. Davenport, Iowa: Association for the History of Chiropractic, 1997.

- Keating, Joseph C. Old Dad Chiro comes to Portland, 1908-10. Chiropractic History 1993 (Dec); 13(2): 36-44.

- Keating, Joseph C. The embryology of chiropractic thought. European Journal of Chiropractic 1991 (Dec); 39(3): 75-89.

- Keating, Joseph C. The evolution of Palmer's metaphors and hypotheses. Philosophical Constructs for the Chiropractic Profession 1992 (Sum); 2(1): 9-19.

- Gaucher-Peslherbe, Pierre-Louis. Chiropractic: Early Concepts in Their Historical Setting. Lombard, Ill.: National College of Chiropractic, 1994.

- Davis, Andrew P. Neuropathy Illustrated: The Philosophy and Practical Application of Drugless Healing. Long Beach, California: Gaves & Hersey, 1915.

- Keating, Joseph C. The short life and enduring influence of the American Chiropractic Association, 1922-1930. Chiropractic History 1996 (June); 16(1): 50-64.

- Parrott, Glenn D. History of Chiropractic in Oregon; unpublished (circa 1962) (Archives, Budden Library).

- Gatterman, Meridel I. W.A. Budden: the transition through proprietary education, 1924-1954. Chiropractic History 1982;2:20-5.

Joseph Keating Jr., PhD

Phoenix Arizona

jckeating@aol.com