Recent laws in New Jersey and California represent a disturbing trend that will negatively impact a practice’s ability to collect monies from patients, as well as expose them to significant penalties if the practice does not follow the mandatory guidelines to a T. Please be aware that a similar law may be coming to your state. The time to act is before the law is passed.

Selected Errors in Insurance Reporting

Contrary to perceptions regarding the review of claims, it is seldom that any insurance company intentionally sets out to cut benefits to either the practitioner or the patient/customer. What is sought is the appropriate expenditure of benefits for services appropriately provided, under the terms of the insurance contract. As history will attest, the insurance industry and employers alike rarely questioned a bill for services submitted by a practitioner on behalf of the patient/customer until the past ten years or so when cost containment factors became a requirement to sustain the profit ratio of doing business. Escalating health care costs are well documented and reported elsewhere. What is germane to this paper is how these new attitudes affect the practitioner of today.

Documentation

Well known throughout the profession is the practice of keeping SOAP notes: i.e., the subjective complaints reported by the patient, the objective findings discovered at examination by the practitioner, the assessment of all findings and complaints to arrive at a diagnosis or determination of what is wrong with the patient, and the plan of treatment considered appropriate for the condition. This plan should also include a prognosis or expectation of care regarding anticipated return to normal function with patient dismissal.

These notes are of particular importance at the onset of care, as well as at intervals thereafter, to demonstrate if the care being rendered is efficacious and if the patient's response is adequate. Should periodic re-evaluation indicate less than adequate response for the diagnosis offered? Perhaps the diagnosis and prognosis should be updated or the therapy utilized be altered or changed. In the health care business, not every patient will respond to treatment equally, for various reasons, nor will every tentative or initial diagnosis remain unchanged as adaptation or correction produce change in clinical findings.

The information reported by the practitioner to the insurance carrier is typically the only information from which a determination of benefits can and is derived. More frequently than not, this initial information is reviewed by non-professionals and compared against frequency parameters established by carrier experience. Should the diagnosis offered not coincide or be found at odds with these parameters, a request for additional information is typically forthcoming. When a practitioner receives this request he must not see it as a personal affront, but merely as what it is -- a request for additional information.

Case Examples

The cases which are true, exact examples taken from recent (1990) files. Review will hopefully highlight certain failures or excesses in reporting which will explain the predictable response from the carrier.

Case 1: A diagnosis of acute subluxation of C1 and 5. Treatment frequency two to three times per week for four months, followed by weekly visits for an additional four months, with care continuing. The practitioner was indignant and threatened to report the carrier to the insurance commissioner's office if payment was not forthcoming, following a request for additional information.

Review:

Well accepted throughout the chiropractic community is the fact that most simple, uncomplicated strains or subluxations should respond, on an average, in six to eight weeks. Without additional information to explain underlying contributory factors or a more descriptive diagnosis, it is no wonder that review was undertaken after eight months of care, particularly with only minimal evidence to suggest diminution of frequency, and with no prognosis or comment regarding anticipated patient outcome.

The case points out the necessity of qualifying your diagnosis and expressing it in terms which are easily understood.

Several items of importance surfaced in this review. The practitioner happens to subscribe to the philosophy that the subluxation is not only a clinical finding, but it is also the diagnosis. The merit of this approach is academic for the purposes of the paper. The individual who reviews all claims initially is not only unfamiliar with the variations in chiropractic philosophy, but in all likelihood, doesn't care to know. He does know that unless substantiation to the contrary is submitted, or the diagnosis offered is more reflective of more than a simple subluxation, the utilization and frequency of care must be within established guidelines and parameters or the claim is pended for further review. The doctor in this case failed to mention that concurrent discogenic spondylosis was/is a factor in the progress of this case. This fact is particularly meaningful in consideration of the diagnosis, i.e., acute subluxation. It is probable that this case commenced care for an acute subluxation complex but that underlying preexisting circumstances contributed to the overall progress and prognosis. If we assume that treatment for the acute episode was successful in controling acute symptoms, it is likely that care rendered after the first four to six weeks was directed towards the secondary diagnosis and, therefore, the diagnosis should have been updated to reflect that treatment was now being rendered towards a chronic, not acute, problem.

This case points out the necessity of qualifying your diagnosis and expressing it in terms which are easily understood.

Case 2: This case offers a diagnosis of acute subluxation of C1, 2, and 5 with myofascial strain/sprain the result of a whiplash injury sustained in an automobile accident. With these qualifiers, claims reviewers recognize that simple parameters do not apply. Accommodation for benefits was provided. However, after two years of frequent care with only a minimal reduction in frequency of utilization, and in the absence of any diagnosis updating or an explanation from the doctor regarding the patient's prognosis, the claim was pended and sent for further review. Unlike case number one, this practitioner then offered no substantiation of concurrent or contributory clinical findings; no history of exacerbation or re-injury; and in fact, reported only that the prognosis was undetermined and that the patient would probably need frequent care for the rest of her life. The patient was 36-years-old at the time of the accident.

This lack of substantiation for ongoing care, i.e., an explanation as to why the patient is not regaining his health or the establishment of documented sequelae as the result of the accident, can only lead to a request for an independent medical examination to help establish an updated diagnosis, prognosis, and a determination of need regarding future care. In the meantime, further benefits will be denied.

Case 3: Certain practitioners seem to have a penchant for gamesmanship regarding insurance reporting. Their claims will typically include 15 to 17 diagnostic codes for every patient. Perhaps the logic is that the reviewer will see all these code numbers and assume that this patient is either really, really ill or that with all these things wrong, additional care will surely be necessary. Unfortunately for these practitioners, the reviewers are serious about their job and take the time to look up all these code numbers. After clearing away all of the NOS (not otherwise specified) codes, and the generic codes such as lumbago, et al., the remaining codes (often repeated for cervical, thoracic and lumbar regions) may adequately reflect a diagnosis. Nonetheless, whatever remains must also be documented by SOAP notes and meet the parameter criteria already established.

The practitioner must serve the patient, and do so in an honest, reliable fashion. Accuracy in diagnosis and reporting is not only a professional responsibility but is morally and ethically required.

This gamesmanship establishes two unwanted responses from all carriers, particularly if it occurs on all claims from the doctor. First, all future claims are red-flagged by the carrier. This means that all of his claims will be carefully scrutinized, even if they involve only one or two visits. While these may eventually be benefited, all payments will be delayed. Secondly, in their quest for code numbers to enlarge the diagnosis, the practitioner frequently reaches and in doing so destroys his credibility. Examples include the reporting of osteoporosis and degenerative disc disease in a fourteen-year-old patient without a history of traumatic or metabolic disorder.

The practitioner must serve the patient, and do so in an honest, reliable fashion. Accuracy in diagnosis and reporting is not only a professional responsibility but is morally and ethically required.

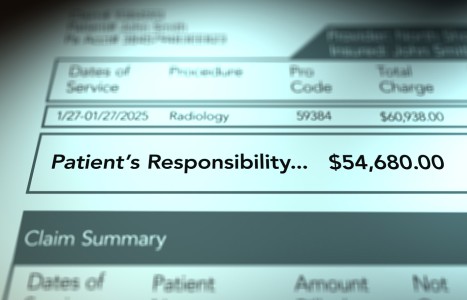

Case 4: Certain practitioners have elected to utilize a particular approach to treatment whose tenents espouse frequent radiography to evaluate response to care and to monitor change of biomechanical function. While the practice may have merit in select cases, e.g., scoliosis, it is not otherwise generally acceptable within mainstream chiropractic, is not taught at any of our accredited institutions, and is therefore not considered usual and customary practice.

Through many years of study and investigation, the profession itself has established standards and guidelines for radiography in chiropractic. In general, the insurance industry has subscribed to these standards, even though recognizing that occasional variations can and do occur. Frequent radiographic examination without substantial documentation of need will typically be denied as a patient benefit. Mere re-evaluation of patient progress, particularly if response to care is adequate, and in the absence of intervening injury or illness, will rarely be found as sufficient evidence of need. Benefits, therefore, will be denied.

This practice of overutilization of radiography is not only considered inappropriate by the insurance industry, but by the profession itself. The potential for significant patient harm from unnecessary ionizing radiation is well documented.

Comment

This brief review of selected cases which are encountered on a daily basis by insurance carriers, has attempted to expose some of the more flagrant abuses. Experience suggests that three types of practitioners, who represent a minor segment of the profession, are responsible for most denied claims and problems between the carriers and the profession. The first of these types may be explained by carelessness in reporting, inattention to necessary documentation and detail, and in some cases professional arrogance. The second type are those practitioners who see the insurance carrier as a golden goose and attempt to milk the system for all it's worth, disregarding the effect on future individual claims and the potential for harm to the image of the profession. The last type, whose numbers are few, are outright fraudulent in their business practices. As they become identified -- and they will be -- more will find their way before state boards for disciplinary action.

While exceptions do exist, it is generally not necessary for the practitioner to assume an adversarial attitude towards the insurance industry. In most cases the doctor, patient and carrier each have well defined roles and obligations to fulfill. If adequate documentation, easily understood reporting, and explanatory notes are provided, and common sense patient management is employed, the frequency and severity of conflicts will be avoided or markedly diminished.