It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

Chondromalacia Patellae and Orthotic Support

Chondromalacia patellae is defined as the pathologic softening of the patellar cartilage, and is associated with patellar tracking disorders.1 With excessive or abnormal biomechanical forces, the hyaline cartilage behind the kneecap undergoes gradual deterioration and fibrillation. The clinical presentation is of "patellofemoral arthralgia," with anterior knee pain made worse after going up and down steps and after sitting for long periods.2 Crepitus and pain during squatting will quickly demonstrate the poor tracking of the patella and the irritated cartilage.

Patellar Tracking

As the knee flexes and extends during gait, the patella glides up and down in the groove between the medial and lateral femoral condyles. The underside of the patella fits into this groove, and the cartilage behind the kneecap reduces friction substantially. Because the knee is a hinge (ginglymus) joint, it moves primarily in one plane. This limits the torsional and lateral deviation forces. Normal interactions between the patellar tendon and the quadriceps muscles keep the patella aligned and moving smoothly with each step. Heavier loads and deeper knee flexion draw the patella closer to the surface of the femur, and can increase friction substantially.

A patellar subluxation, or disturbance of its normal juxtaposition to surrounding structures, will cause the patella to rub and grind with each sliding movement. Patellofemoral pain syndrome starts when abnormal tracking is ongoing, and muscle imbalance develops.3 If this is allowed to continue, it will result in patellofemoral arthralgia, and begin to cause the articular cartilage to undergo degeneration. Eventually, wearing away of the cartilage on the underside of the patella (chondromalacia patellae) and degeneration of the articular surfaces of the knee (DJD) is found. At this point, permanent damage has been done, and complete recovery is often difficult.

Abnormal tracking of the patella in the femoral groove develops in association with two major lower extremity malalignments: a high Q-angle and excessive pronation at the foot. Each of these conditions will interfere with the smooth gliding of the kneecap, and both can be improved or corrected with the use of orthotic supports.

The Q (Quadriceps) Angle

The Q-angle is formed by the pull of the quadriceps muscles (primarily the rectus femoris) from the pelvis to the patella, and the patellar tendon's pull on the tibia.4 Since large forces are transmitted through the patella during each extension of the knee joint, misalignment will cause problems with kneecap tracking. Measuring the angle provides useful information regarding the alignment of the knee in the frontal plane, and possible underlying abnormal biomechanics.

Measurement of the Q-angle requires only a goniometer with long arms. First, the center axis of the long-arm goniometer is placed over the center of the patella. Next, the lower goniometer arm is aligned with the patellar tendon to the tibial tubercle. Finally, the upper arm of the goniometer is pointed directly at the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). The small angle measured by the goniometer is the Q-angle. Since slight variations in patient positioning have a significant effect on the measurement of the Q-angle, and measurement reliability in the supine position is only moderate,5,6 the best way to perform this test is with the patient standing. This has the advantage of measuring the Q-angle in the patient's usual upright posture, so that the normal weightbearing stresses (such as valgus stresses on the knee and internal rotation forces due to excessive foot pronation) are included in the measurement. Standing measurements will more accurately assess how the knee functions during everyday and sports activities.

When measured standing, the Q- angle should fall between 18 and 22 degrees.7 Males are usually at the low end of this range, while females (because of their wider pelvis) tend to have higher measurements. One author considers standing Q-angles greater than 25 degrees in females and 20 degrees in males to be abnormal.8 When measured in the supine position, the values will be lower, and the normal range ends at 15 degrees in males and 20 degrees in females.9 A Q-angle measured at the higher end of the normal range indicates a tendency for added biomechanical stress during strenuous or repetitive activities using the knee. When the measurement is above the normal limits, the probability of developing tracking disorders and chondromalacia patellae increases rapidly.

Excessive Foot Pronation

When the foot and ankle go into excessive pronation, it causes an increased medial rotation to be transmitted up the leg, adding more rotary motion to the ginglymus knee joint. Prolonged time in pronation causes excessive internal rotation of the tibia, impeding its normal external rotation during gait progression in the stance phase. This excessive inward tibial rotation transmits twisting forces upward in the kinetic chain, producing medial knee stresses, forcing vector changes of the quadriceps mechanism, and lateral tracking of the patella.10 Knee problems are closely associated with low arches and excessive pronation, especially in athletes, who experience greater rotational forces.11 Athletes with excessive pronation develop biomechanical (noninjury) knee problems, such as patellofe-moral pain syndrome, chondromalacia patellae (the "kneecap tracking problems"), capsulitis and pes anserine bursitis.12

Subtalar joint pronation and internal rotation of the tibia normally occur only during the initial, contact phase of gait. If pronation continues beyond the contact phase, the tibia will remain internally rotated. This theory is supported by Copland's work, which found that passive tibial rotation was statistically greater in hyperpronators than in nonpronators.13 Interestingly, whenever a patient has excessive pronation of the foot, Q-angle stresses are magnified. The combination of a higher Q-angle with excessive pronation will cause a more rapid progression from knee dysfunction to patellofemoral arthralgia to chondromalacia patellae and degenerative disease.

Orthotic Support

The most effective way to decrease a high Q angle and to improve the tracking of the patella is to prevent excessive pronation with custom-fitted foot orthotics.14 The orthotics should support all three arches (especially the medial longitudinal arch) and may need to include a pronation wedge for the calcaneus. One study has found that using soft corrective orthotics is more effective in reducing knee pain than a traditional exercise program.15

The orthotics provide support for the arches, which reduces excessive pronation, decreases the Q angle, and limits medial rotation, thereby improving tracking of the patella and reducing the torque forces on the connective tissues. A well-made orthotic will also help the foot absorb the shock of heel strike, which can significantly decrease the vertical loading forces on the knee joint. The best orthotics for use in chronic knee conditions and patellar tracking disorders will have a layer of visco-elastic material. A built-in heel cup can lessen the dynamic vertical forces even further.

Exercise Support

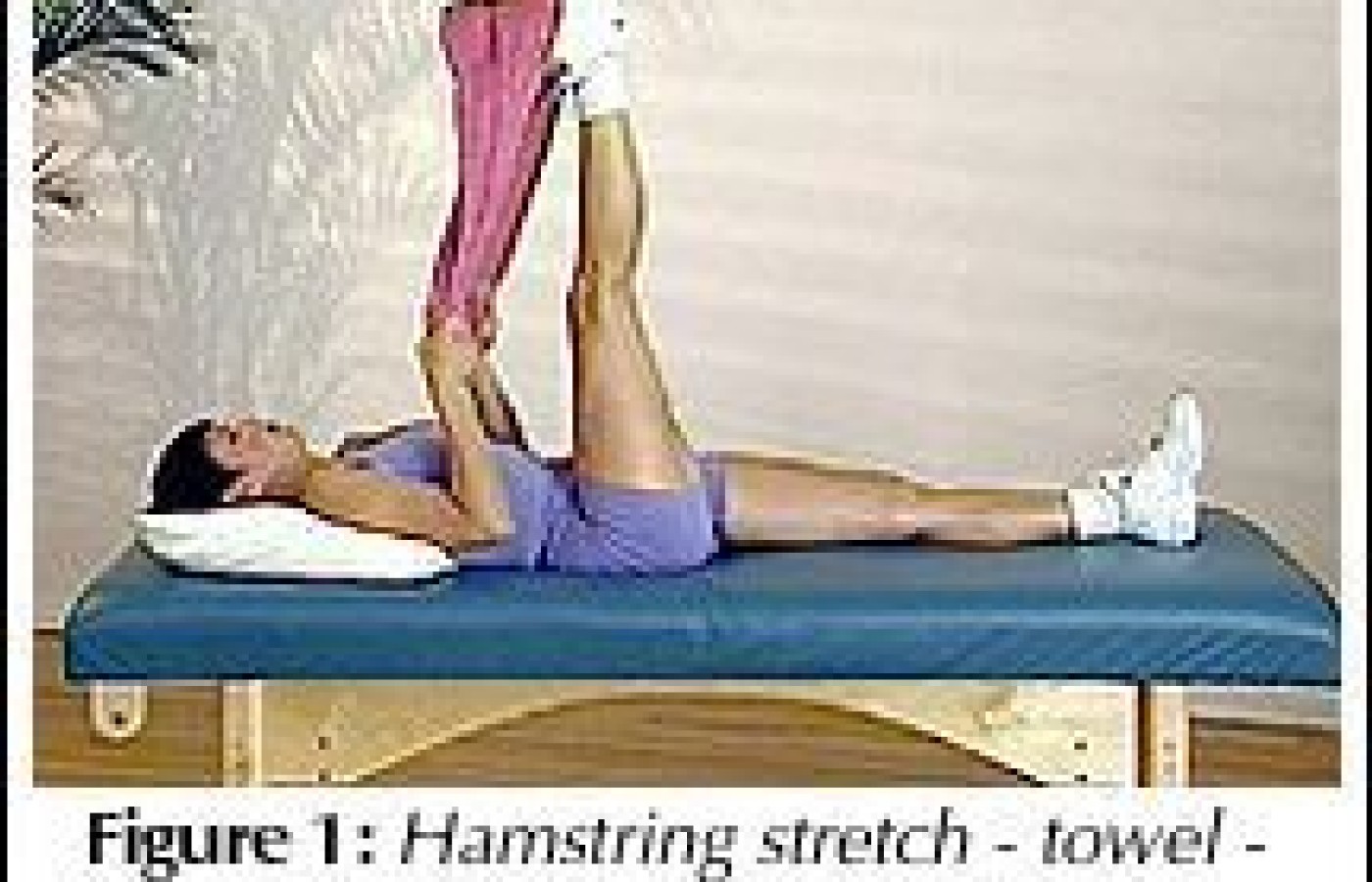

Chondromalacia patellae is a condition that responds favorably to a well- devised exercise regime. Caution must be taken in prescribing routines that progress the patient from a painful condition to improved daily function. This generally includes a beginning of carefully positioned stretch routines to isometric and functional patterns. Figures 1-4 are common patterns prescribed at various stages of treatment progression.

Outcomes Assessment

To assess the effectiveness of a chondromalacia patellae treatment plan, both objective and subjective data on patient results on outcomes must be collected and documented. The data typically focus upon the physical changes noted at the time of consultation and in subsequent visits. Ongoing outcome assessment data utilizing the Patellof-emoral Function Scale with comparative graphs on www.outcomesassessment.org) documents the long-term results and effectiveness of the rehabilitation procedures.

Conclusion

Chondromalacia patellae is an excessive wearing of the cartilage covering a kneecap that has not been tracking properly. Abnormal biomechanical forces, especially a high Q angle and excessive foot pronation are frequently found as underlying causes. When the Q angle is elevated in a patient with a patellar tracking disorder, correction of excessive foot pronation has been shown to be the single most effective treatment. All patients with symptoms of anterior knee pain (patellofemoral arthralgia) should be evaluated for the presence of a high Q angle and excessive pronation. Custom-fitted orthotics designed to reduce pronation are usually necessary. In addition, adjustments and exercises should be considered to ensure a rapid and complete response to treatment.

References

- Yochum TR, Rowe LJ. Essentials of Skeletal Radiology (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1996:446.

- Souza TA. Differential Diagnosis for the Chiropractor. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Pubs., 1997:302.

- Galea AM, Albers JM. Patellofe-moral pain: targeting the cause. Phys Sports Med 1994;22.

- Magee DJ. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1987:296.

- Olerud C, Berg P. The variation of the Q-angle with different positions of the foot. Clin Orthop 1984;191:162-165.

- Tomsich DA et al. Patellofemoral alignment: reliability. J Ortho Sports Phys Ther 1996; 23:200-208.

- Loudon JK, Jenkins W, Loudon KL. The relationship between static posture and ACL injury in female athletes. J Ortho Sports Phys Ther 1996;24:91-97.

- Post WR. Patellofemoral pain: Jet the physical exam define treatment. Phys Sports Med 1998; 26:

- Hvid I, Anderson LB, Schmidt H. Chondromalacia patellae: the relation to abnormal patellofemoral joint mechanics. Acta Orthop Scand 1981;52:661-669.

- Tiberio D. The effect of excessive subtalar joint pronation on patellofemoral mechanics: a theoretical model. J Ortho Sports Phys Ther 1987;9:160-165.

- Dahle LK, et al. Visual assessment of foot type and relationship of foot type to lower extremity injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1991; 14:70-74.

- Hartley A. Practical Joint Assessment: A Sports Medicine Manual. St. Louis: Mosby Yearbook, 1991:571.

- Copland JA. Rotation motion of the knee: a comparison of normal and pronating subjects. JOSPT 1989;10:366-369.

- D'Amico JC, Rubin M. The influence of foot orthotics on the quadriceps angle. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 1986;76:337-340.

- Eng JJ, Pierrynowski MR. Evaluation of soft foot orthotics in the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Phys Ther 1993;73:62-70.