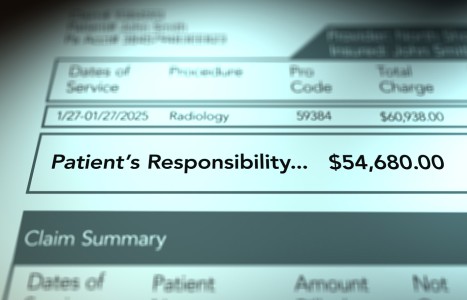

Recent laws in New Jersey and California represent a disturbing trend that will negatively impact a practice’s ability to collect monies from patients, as well as expose them to significant penalties if the practice does not follow the mandatory guidelines to a T. Please be aware that a similar law may be coming to your state. The time to act is before the law is passed.

A Day in the Life of a Chiropractor in Israel

The weather in Israel and California is the same. Everything is dry and hot in the summer, and in the winter the rainy season sets in and there is plenty of water. It is a time when the desert is green and full of flowers - but that is where the resemblance ends.

I look out of my window and see shepherds driving Arab sheep down in the wadis (valleys). They have kafias (scarfs) on their heads. The sun beats down unmercifully. It is a scene out of a Cecil B. De Mille movie with Moses leading the Jews out of Egypt as the Pharaoh closes in behind.

I live in a little yishuv (settlement) right next to Ramallah, and I can see Yasser Arafat's (Palestinian leader) compound from my roof. We are surrounded by structures on three sides.

Today I am going to my office in Jerusalem. It is a free or "nearly-free" clinic. I am traveling in an armored bus. As I sit in my seat I see that a machine gun bullet has pierced the outer plastic window of the bus, but the inner bullet-proof glass is intact. It has stopped the .30-caliber shell that lies between the two windows. The bullet hole is at the level of my heart. I wasn't there when it happened, but the hole wasn't there yesterday.

The ride takes an hour and the cost is cheaper than that of a city bus. The Israeli government subsidizes the settlement buses so that people won't use their cars, which are not bulletproof. I can get a bulletproof vest if I want one, but they are heavy (about 23 pounds) and I don't want to wear them. I do carry a Beretta 9mm automatic with a 20-bullet clip - just in case.

We pass through the army blockade on the way to the city. The bus stops; a soldier boards to check all the passengers; and he opens garbage cans to check for bombs. We pass inspection and are soon in downtown Jerusalem.

Jerusalem is divided into three sections: Jewish, Arab and Christian. There is not too much traffic between them. The Jewish section is divided into subsections: nonreligious, religious and "ultraorthodox." My office is in the ultraorthodox section. A sign at the entrance to this quarter says, "Please do not offend us by immodest dress. Women are requested to wear long sleeves, blouses buttoned to the neck, and skirts to midcalf." Noncompliance with the posted "request" can result in the violators being "escorted" out of the neighborhood.

The resident males are dressed in long black coats and large black hats that look like black bowlers, but with square tops and hard edges. The men's hair is cut short, but they customarily wear long hair curls at the ears, usually down below the chin.

Men stay in the Rabbinic academies to learn the Jewish law or own businesses. Usually, the wives run the businesses and the men learn. They learn from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. The boys go to school the same hours, six days a week. The girls go to school from 9 a.m. to about 2 p.m., then typically go home to help their mothers with the children. Many families have six to 15 children, and the mothers need help. Boys and girls are strictly separated, and even married men and women keep separate company. (This does not mean that husbands and wives do not spend time together. They do, and they make time to enjoy each other's company.)

My office is in a medical building. I share my office with "Dr. O," an MD. Because medicine is not a very high-paying profession in Israel, there is very little rivalry between us. He sends me patients on a regular basis, and I refer in return.

Dr. O is also an orthodox Jew, and dresses completely in black and has hair locks. I consider myself a more "modern" dresser. I do not have hair locks; however, I dress in black and have a kipah (skullcap) and a black Stetson (not the American cowboy type) hat.

Today I have a fair patient load. The first patient is Reb (Mr.) Yaakov (first name). He has what he calls a "crank" (pain) in his back and some symptoms of asthma.

"How do you feel?" I ask him. "Thank G-d," he replies. (Out of reverence, Jews do not put the Almighty's entire name in print, because the paper will eventually be thrown away and they don't want His name in the trash.)

"How did you feel yesterday?" I ask. "Thank G-d," he says.

"Is there any change from last week?" Once more: "Thank G-d."

"Reb Yaakov," I say, "if you don't tell me what is going on, it's very difficult to help you."

He explains to me, "You have to thank G-d for everything - the good and the bad."

I've heard this same pattern of response a thousand times before, but still I have to go through the ritual.

I ask him how old he is; he won't tell me. "You shouldn't count your days," he says.

"Well, how old would someone be if he was near your age?" I ask, to which he replies, "About 42."

"How many children do you have?" I ask, and receive the answer, "A minyan" (a quorum of 10 men that make up a prayer meeting).

Eventually, I get all the information I need. Now I can proceed with my work. I perform my pulse diagnosis and treat him with a combination of chiropractic, osteopathy and acupuncture.

When he gets off the table he tells me that his breathing is better, but he still has the "crank."

"Come back tomorrow and we will see what is what," I advise. Chances are that he will feel much better soon. He may need one or two more visits, though, since he had the same problem last year, and four visits was all he needed.

After many more patients, the day is over. I get back on the bus. There are no new bullet holes in it. I unlock the leather strap over the hammer of my Beretta and cock it. It's still an hour bus ride home.

Rabbi Shmuel Brody,DC

Jerusalem, Israel