It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

Medical and PT Management of Chronic LBP Continues to Fail and Bypass Chiropractic

- The evidence in the literature strongly suggests that to help eradicate the low back pain epidemic, and reduce the use and costs of opioids, chiropractic should be the first provider.

- “Despite evidence for managing low back pain, the gap between the evidence and practice is pervasive. This is evidenced by too many highly regarded medical institutions continuing to recommend less successful pathways to help curb opioid use.

- Despite the variety of conventional treatments, excluding chiropractic care in many approaches is a missed opportunity to enhance patient outcomes by reducing disability, absenteeism, and decreased productivity.

Despite efforts from clinicians and researchers to understand disease mechanisms and to develop new treatment paradigms, the burden of nonspecific low back pain (NSLBP) continues to rise.1

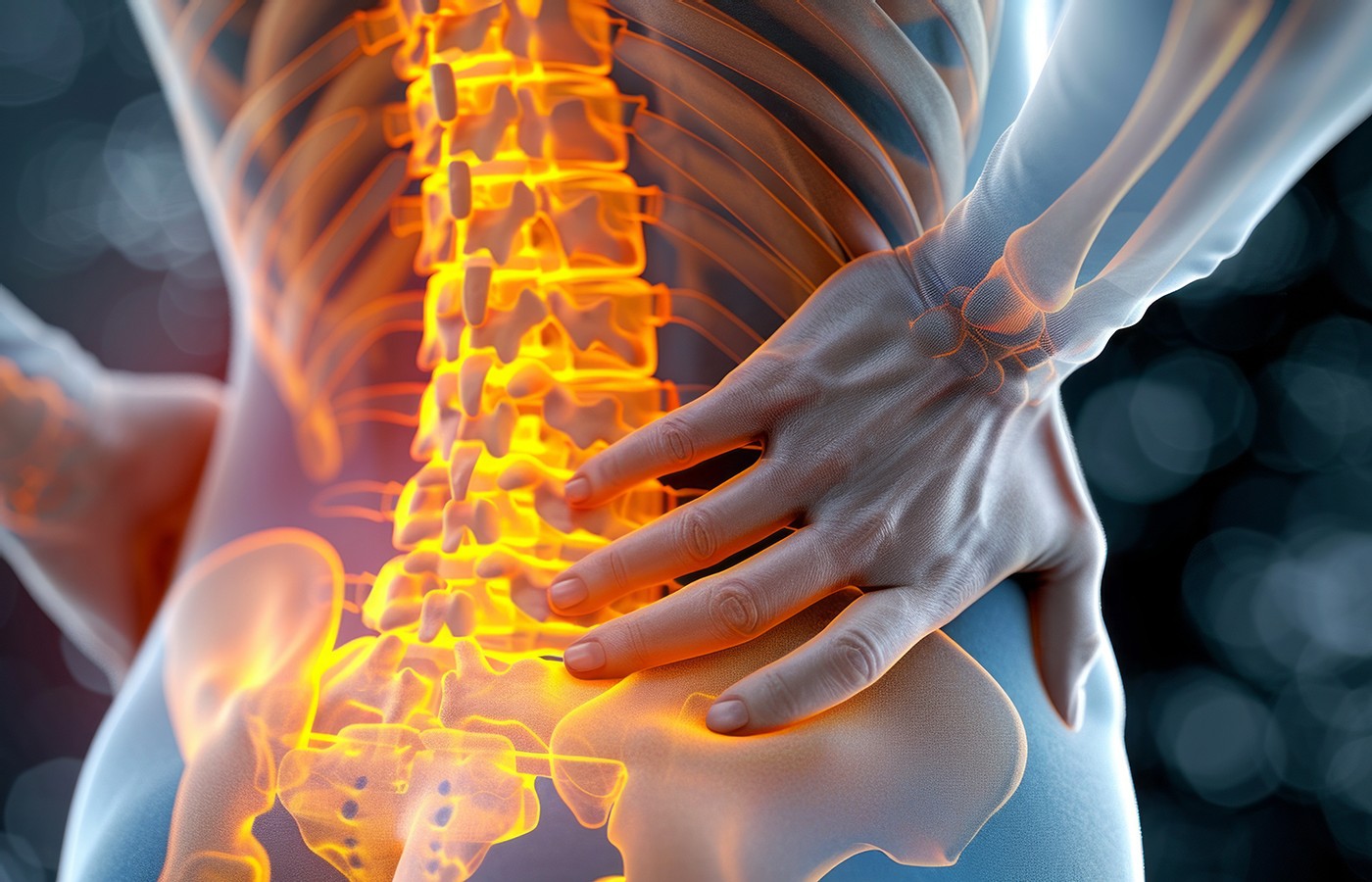

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) continues to be one of the leading causes of disability and health care expenditures globally. Low back pain is reportedly benign and self-limiting, yet affects 20% of the world’s population and is widely accepted as non-specific.

CLBP has affected “quality of life” issues such as work, social issues, and retirements related to disability. Societal costs for CLBP are perhaps the highest of all health conditions, including absenteeism and decreased productivity.1

CLBP has been associated as a cause, from somatic to psychosocial factors, with physical therapy continuing to be the “first line” of treatment, albeit with an unclear approach that the physical therapists should take.2

In medicine, low back pain (LBP) and CLBP fall under non-specific LBP and are defined by pain without an anatomical pathology readily seen (i.e., fracture, tumor, infection, herniations). In essence, it is pain without a pathoanatomical cause.11 Herein lies the root of the problem.

“Despite evidence for managing low back pain, the gap between the evidence and practice is pervasive.”3 This is evidenced by too many highly regarded medical institutions continuing to recommend less successful pathways to help curb opioid use.

States such as New York are taking opioid reduction to the next level and recently signed into law S.4640, a mandate for providers to consider opiate alternatives, including allopathic non-opioid and non-allopathic pathways to treat neuromusculoskeletal conditions before prescribing opioids.

Regarding the largest users of opioids, back pain patients, who account for approximately 50% of opioid use, the care path should follow the evidence in the literature. The arbiter for low back pain, as all treatment, should follow evidence-based outcomes.

Even though there are many stakeholders in this $750 billion back pain industry, the evidence shows that physical therapy realizes upwards of an 80% increase in opioids in 90% of patients, with a 0% re-education in the last 10%.4 In contrast, chiropractic has a 55% reduction in opioid use for the same population of low back pain patients with a 74% decrease in opioid drug costs.5-6

Consistent with those statistics, chiropractic has reduced secondary disability by 313% compared to physical therapy for back-related conditions and by 239% for primary disability,7 whereas medicine is diagnosing 95% of patients with low back pain as nonspecific and predominantly referring to perpetual failed pathways.

At the same time, chiropractic helps 96% of its patients (based on a cohort of 8,000,033 over four years), including low back pain.8 This is not a referendum against physical therapy or medicine, as collaboration with every health care discipline is required, and each provider brings a unique skill set to the health care marketplace.

However, with low back pain, the evidence in the literature strongly suggests that to help eradicate the low back pain epidemic, and reduce the use and costs of opioids, chiropractic should be the first provider.9

In developed countries, current management strategies10 for CLBP primarily emphasize non-pharmacological interventions, such as:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): A psychological approach to help patients manage pain by changing how they perceive and react to it.

- Exercise: Tailored physical activity to strengthen muscles, improve mobility, and reduce pain.

- Biopsychosocial management: Addressing physical, psychological, and social factors contributing to pain.

- Educational interventions: Teaching patients about pain management techniques and how to prevent future episodes.

The following regimen is currently considered “appropriate for CLBP”; this includes pharmacological treatment.10

- Extensive use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Passive therapies: Sick leave, rest, massage, and heat therapy

- Manual therapy: Techniques like joint movements and mobilization performed by health care professionals, including chiropractors.

- Routine imaging: Such as X-rays or MRIs, often followed by prescription medications like Paracetamol (acetaminophen), opioids, serotonin-type drugs, antidepressants, or anticonvulsants for pain control.

To help resolve the non-specific back pain and CLBP issues, emergency departments have placed physical therapists in the ERs in an attempt to provide early intervention. The results were the same as those of the general population worldwide. It was reported that the effects of physiotherapeutic intervention had only minimal improvement in disability but without a reduction in pain.11

This raises the question as to why an unsuccessful care path would be duplicated, expecting different results.

In 2024, based on a focused literature review of treatments for CLBP, many therapies emerged or re-emerged in new applications of existing care: connective-tissue massage, dry needling, dry needling with exercise, lumbar bracing and other assistive devices, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, shoulder soft-tissue treatments, and laser acupuncture.12-14

Despite the variety of conventional treatments, excluding chiropractic care in many approaches is a missed opportunity to enhance patient outcomes by reducing disability, absenteeism, and decreased productivity. Chiropractic interventions have shown effectiveness in managing musculoskeletal issues like CLBP, and they should be considered the “primary spine care provider” or first option for mechanical spine pain based on evidence-based outcomes. This includes working collaboratively with other providers as clinically indicated.

When reviewing the dates of evidence in the literature supporting chiropractic’s efficacy – based on patient outcomes, it becomes clear that this research predates the 2024 current reports referenced in this article of rising incidences of chronic low back pain (CLBP), “regurgitating failed treatments,” and worsening societal statistics while ignoring chiropractic outcomes.

This raises the question: Why is an entire care path that disproves the label of “non-specific low back pain” being ignored? Yet, the tag of NSLBP is “dogmatically held on to” – despite the positive outcomes rendered by 8,000,033 LBP sufferers with chiropractic care.

References

- de Bruin LJE, et al. Insufficient evidence for load as the primary cause of nonspecific (chronic) low back pain. A scoping review. JOSPT, 2024;54(3):176-189.

- Baroncini A, et al. Physiotherapeutic and non-conventional approaches in patients with chronic low-back pain: a level I Bayesian network meta-analysis. Scientific Rep, 2024;14(1):11546.

- Foster NE, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet, 2018;391(10137):2368-2383.

- Farrokhi S, et al. The influence of active, passive, and manual therapy interventions for low back pain on opioid prescription and health care utilization. Phys Ther, 2023:pzad173.

- Whedon JM, et al. Association between utilization of chiropractic services for treatment of low-back pain and use of prescription opioids. J Alt Compl Med, 2018;24(6):552-556.

- Whedon JM, et al. Association between chiropractic care and use of prescription opioids among older Medicare beneficiaries with spinal pain: a retrospective observational study. Chiro Man Ther, 2022;30(1),

- Blanchette MA, et al. Association between the type of first healthcare provider and the duration of financial compensation for occupational back pain. J Occup Rehab, 2017;27(3):382-392.

- Ndetan, H., et al. "Chiropractic Care for Spine Conditions: Analysis of National Health Interview Survey." Journal of Health Care and Research 2020.2 (2020): 105

- Studin M, et al. “Lumbar Disc Herniation and Biomechanical Dysfunction - A Case Study. Discussion of - The Outcome Assessment of Physical Therapy And Chiropractic Spinal Adjustments On Low Back Pain, Opioid Use, and Health Care Utilization.” Medpix: National Institute of Health/National Library of Medicine, published March 3, 2024.

- Ampiah JA, et al. ‘Specialist before physiotherapist’: physicians’ and physiotherapists’ beliefs and management of chronic low back pain in Ghana – a qualitative study. Disab Rehab, 2024:1-11.

- Chrobok L, et al. On-site physiotherapy in emergency department patients presenting with nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med, 2024;13(11):3149.

- Mao X, et al. Efficacy of laser acupuncture for treatment of chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Manag Nurs, 2024 Oct;25(5):529-53.

- Cansu D, et al. The effects of connective tissue massage and classical massage on pain, lumbar mobility, function, disability, and well-being in chronic low back pain: a three-arm randomized controlled trial. EXPLORE, 2024:103029.

- Akbar MS, et al. The effect of using back support (orthosis) on non-specific back pain in adults. Int J Health Sci, 2022:6(S8):2356-2364.