It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

Spotting Heterotropic Ossification

- Heterotropic ossification can become a serious, debilitating complication after total hip replacement.

- Health care providers need to be aware of this complication; especially those of us who treat musculoskeletal disorders.

- Often HO presents as an incidental finding on plain radiograph. The heterotopic bone typically forms in the connective tissue between the muscle planes around the femoral neck and adjacent to the greater trochanter.

Heterotopic ossification (HO) is the term used to describe bone that forms in a location where it should not exist. Heterotopic ossification is the formation of bone within soft tissues, including muscle, ligaments or other tissues. HO can occur anywhere in the body and often forms after surgery and trauma, although frequently the etiology is not known.

HO After Hip Replacement

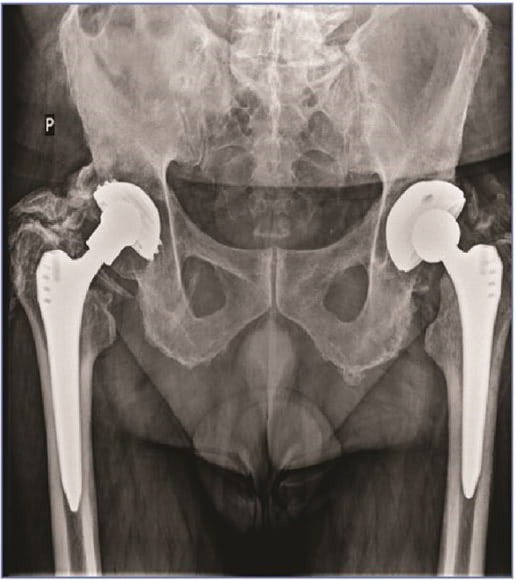

HO can become a serious, debilitating complication after total hip replacement. (Fig. 1) The incidence of HO after total hip arthroplasty (THA) varies widely from 15% to 90% depending on the patient population. The consensus is that the incidence of HO is about 53% in THA, with one-third of cases clinically significant.1-3

What does this mean? It means that the presence of HO is not uncommon, but generally is not a clinical problem if it does not inhibit joint function. Only 30% of the time when HO is present does it become a significant clinical complication.

According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, more than 450,000 total hip replacements are performed each year in the United States. This is a challenging complication since none of the numerous international or national orthopedic associations has yet developed guidelines for the prevention and management of patients with existing heterotopic ossifications.1, 3-4

Presentation and Risk Factors

The bone that develops in HO presents in areas of soft tissue outside of the joint capsule. This process is poorly understood; the bone appears be the same as normal bone, only in the wrong place. It has its own vascular supply and because of this vascularity, HO bone can grow at three times the normal rate, causing destruction and pain in the joint. Mature HO shows cancellous bone growth as well as lamellar bone, blood vessels and bone marrow.

The known risk factors for postoperative HO include excess weight, older than age 65, male, presence of excessive osteophytes, previous HO, posttraumatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Other associated factors are having cemented type of prosthesis and a bilateral procedure.

Genetic conditions, such as fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva and progressive osseous heteroplasia, and traumatic brain or spinal cord injury and sports injuries (myositis ossificans), are also associated with HO.

Clinical Signs

Health care providers need to be aware of this complication; especially those of us who treat musculoskeletal disorders. The most common symptom of HO is stiffness of the joint. Symptoms usually develop within 3-8 weeks postoperatively.

Often HO presents as an incidental finding on plain radiograph. The heterotopic bone typically forms in the connective tissue between the muscle planes around the femoral neck and adjacent to the greater trochanter. If the amount of bone formation is minimal, most patients are asymptomatic.

Most people who develop heterotopic ossification cannot feel the abnormal bone, and are able to maintain function and range of motion of the hip joint. There is minimal amount of bone growth, and it abates without causing any significant restriction of motion. But in some patients the HO continues to grow, eventually restricting the function of the joint.

Confirming a Diagnosis

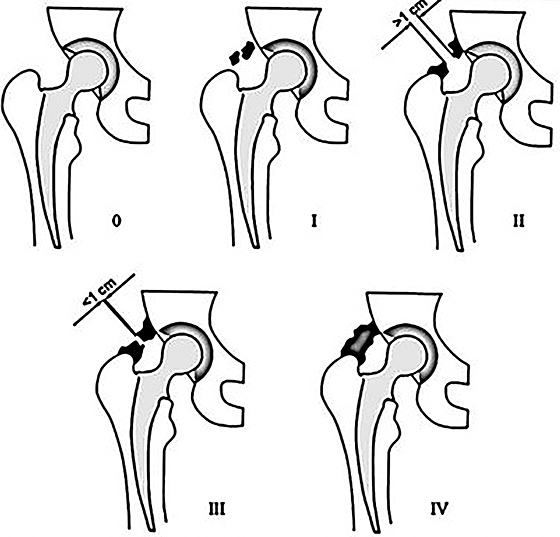

Conventional radiography followed by three-phase bone scanning is considered the best protocol for confirming the diagnosis of HO. The most common method of grading HO in the hip is the Brooker Classification:4 (Fig. 2)

- I: described as islands of bone within the soft tissues about the hip.

- II: consisting of bone spurs originating from the pelvis or proximal end of the femur, leaving at least 1 cm between opposing bone surfaces.

- III: consisting of bone spurs originating from the pelvis or proximal end of the femur, reducing the space between opposing bone surfaces to less than 1 cm.

- IV: hip joint ankylosis.

Note: Only types III and IV are referred to as clinically relevant.

Grades I and II HO may not need treatment unless they become symptomatic or functionally disabling. The gold standard therapy for grades III and IV HO is a revision arthroplasty and surgical resection of the ossifications.

To lower the risk of intraoperative complications such as excessive bleeding, and postoperative complications such as recurrence of HO, the surgery must be performed when the HO is mature. Once it has matured (usually less than a year), it will cease growing. The best diagnostic tool for following the maturation process is the bone scan.

Treatment: Challenging & Limited

Treatment of HO is difficult because little is understood about what triggers this bone formation. A great amount of bone metabolic turnover markers have been tested, but none of them seems to be relevant in for the prevention or diagnosis of HO. So far, the most effective prophylactic treatment is radiotherapy or administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs pre- and/or post-surgery.

However, most patients don’t need such aggressive therapy, since the majority do not develop clinically significant HO, and these therapies carry their own issues and side effects.

Keep in mind that the strongest risk factor of HO development is previous history of HO, so prophylactic treatment must be administered after the surgery.3

In patients who have a genetic disorder that has caused the heterotopic bone to form, surgery is the wrong treatment. In fact, in these patients, performing surgery to remove the heterotopic bone may worsen the overall condition.

In patients with known genetic or very high risks factors for forming OH, certain medications, including high doses of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), have been shown to decrease the development of heterotopic bone. Radiation treatment in a single dose to alter the cells that produce the excess bone formation has also been used, but is still controversial, as radiation can cause tissue damage and delayed healing where surgery has been performed.

Unfortunately, there is a lack of consensus on standardized treatment guidelines for acquired HO. Hopefully as our understanding of this type of bone formation improves, standardized treatments will be developed.

As health care professionals, we need to be cognizant of this complication to ensure patients are appropriately managed and treatment is optimized.

References

- Łegosz P, Otworowski M, Sibilska A, et al. Heterotopic ossification: a challenging complication of total hip arthroplasty. Risk factors, diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment. BioMed Res Int, 2019;2019:3860142.

- Biz C, Pavan D, Frizziero A, et al. Heterotopic ossification following hip arthroplasty: a comparative radiographic study about its development with the use of three different kinds of implants. J Orthop Surg Res, 2015 Nov 14;10(1):176.

- Lespasio M, Guarino AJ. Awareness of heterotopic ossification in total joint arthroplasty: a primer. Permanente J, June 1, 2020:24:12.211.

- Hayashi D, Gould ES, Ho C, et al. Severity of heterotopic ossification in patients following surgery for hip fracture: a retrospective observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2019 Jul 27;20(1):348.