It’s a new year and many chiropractors are evaluating what will enhance their respective practices, particularly as it relates to their bottom line. One of the most common questions I get is: “Do I need to be credentialed to bill insurance, and what are the best plans to join?” It’s a loaded question – but one every DC ponders. Whether you're already in-network or pondering whether to join, here's what you need to know.

"Chief Complaints" in Narrative Reports

Narrative reports can be difficult to understand because of the way in which they are constructed. Very often, only the writer knows for certain how to interpret the report. This section, "Chief Complaints," is the part of the report where confusion often begins. For example, when I read a report which is dated 11/5/93 and the date of injury was 5/5/92, the question of chronology immediately pops into mind. Are the chief complaints described in the November 1993 narrative report those of May 1992, or are they the ongoing complaints in November of 1993, 18 months later? Similar confusion arises in "Physical Examination," and "Diagnostic Impression" sections. Frequently clinicians list a series of original diagnoses in reports written months, or in some cases years later. The reader is then left to solve the puzzle as to what the current diagnoses are, if any. This same thing happens with physical examination findings. Ultimately, if you don't specify the chronology, your reader will have to guess. And, if you make them do that, they'll have a few "chief complaints" of their own.

When writing a report months or years later after an injury, I like to subdivide the "Chief Complaints" section into two parts: 1) original chief complaints and 2) current chief complaints. When I perform IMEs, I do the same with my history taking, explaining to the patient that first I want to hear all about the complaints they had right after the accident. Once we've concluded our discussion of that we'll switch over to how they are feeling lately. A good method of doing this is to take each complaint in the order of its importance to the patient. That way complaint number one is the most significant (at least to the patient), number two is the next most significant, and so on. And, as an extension of this, I list diagnoses in the same order if possible. That way if ever I'm called upon to review one of my cases, a glance is all I need to learn the relative significance of these complaints and diagnoses. One of the most important ways of streamlining an office is to maintain consistency.

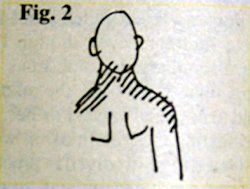

Another part of this method is to utilize the OPQRST mnemonic and to draw pictures of the patient's complaints in the margin immediately to the left. By augmenting your medical shorthand with drawings you can save yourself large blocks of time. And, when you dictate, your anatomical accuracy will be excellent. For purposes of accuracy and for mediolegal reasons, I ask people to show me with their hands the area and extent of their pain. I then make quick drawing and show it to them. "Like this?" I ask.

Here's an example from the form I use. First I'll fill in the blanks, using as much shorthand as possible, and then I'll draw pictures out in the margin. The codes are as follows:

CC: chief complaint

O: onset

Pr: provocative factors

Pa: palliative factors

Q: quality of pain, etc.

R: radiation

S: severity

T: temporal element

1) CC: L: LBP, R: LP

O: MVA

Pr: sit > 10", stand >30", stooping

Pa: CMT, PT rest

Q: dull ache -- LB; sharp -- LP

R: ↓

S: LB 2 1/2 - 3+; LP 1 1/2 - 2+

T: LB const., daily; LP int., 3-4 d/w

2) CC: B: neck pain

O: MVA

Pr: all movements of neck; reading; driving

Pa: CMT, PT, ice, IBV

Q: "burning pain"

R: ↓ R: delt.

S: 2-3+

T: almost const.

When I dictate this report, it will go something like this:

- Constant and daily, slight to moderate low back pain, which began immediately after the MVA of 3/16/94. It is aggravated by sitting for more than ten minutes, standing for more than 30 minutes, or by stooping, and is relieved by manipulation, physiotherapy modalities, and rest. The pain is described as diffuse dull ache on the left from L2 to L5 levels, and a sharp, focal pain at the right posterior superior iliac spine.

- Intermittent pain in the posterior right thigh, extending to the level of the knee. Provocative and palliative factors are as described as #1 above. The pain is described as sharp and is minimal to slight in severity. This began after the MVA and is associated with the low back pain.

- Bilateral neck pain, which began immediately after the MVA of 3/16/94 and is aggravated by all motions of the neck as well as by reading and driving. It is relieved by manipulation, physiotherapy modalities, ice, and ibuprofen. It is described as a "burning pain" which radiates across both trapezius ridges and into the right deltoid region. It is slight to moderate in severity, and is nearly constant.

If it seems like a mouthful, let me just point out that all of these details are indispensable, yet all came from that simple history form and quick sketch. It took me just a little bit longer to dictate it than it did for you to read it. Incidentally, when I take the history of original chief complaints, I dispense with the details about provocative and palliative factors since patients can't reliably remember these details for long.1

Reference

1. Croft AC: Whiplash: The Masters' Program. Module 3, Narrative Report Writing (second edition). Coronado, 1994, p45-49.

Arthur C. Croft, DC, MS, DABCO

Coronado, California