When sports chiropractors first appeared at the Olympic Games in the 1980s, it was alongside individual athletes who had experienced the benefits of chiropractic care in their training and recovery processes at home. Fast forward to Paris 2024, where chiropractic care was available in the polyclinic for all athletes, and the attitude has now evolved to recognize that “every athlete deserves access to sports chiropractic."

The Psoas Major May Not Function As You Think

I just read a chapter by S. Gibbons in Andry Vleeming's new textbook1 that totally alters accepted information regarding the psoas major muscle. Is the psoas major (PM) the chief flexor of the hip and does it cause anterior tilting of the pelvis when shortened? Probably not.

The PM can almost be regarded as two separate muscles, especially since it has a dual nerve supply. The PM must first be broken down into an anterior and posterior portion, with the anterior fibrous attachment originating from the anteromedial aspect of all the lumbar discs and adjoining bodies, excluding the L5-S1 disc. These anterior fasciculii are supplied by branches of the femoral nerve from L2, L3 and L4. The anterior fibers are important in maintaining or producing the lumbar lordosis, lowering the spine eccentrically during side flexion and controlling side flexion during gait. The posterior portion of the PM originates from the anteromedial aspect of all the lumbar transverse processes. The nerve supply to the posterior fasciculii comes from branches of the ventral rami. The location of the posterior portion of the PM with its segmental attachments may be more important as a spinal stabilizer in controlling lumbar segmental translation.

The primary force of the PM on the lumbar spine is axial compression, which creates segmental stiffness and thereby resists shear forces. Most of this activity comes from the anterior fasciculii. The PM hardly contributes to spinal movement since it is too close to the axis of rotation. The PM contributes to maintaining the neutral lumbar lordosis since it causes a small amount of extension at L1, L2 and L3 and a small amount of flexion from L4 and L5. The PM runs inferolaterally to become a central tendon where it joins the iliacus strongly attaching to the pelvic brim (iliopectineal eminence), causing it to exert a force on the sacroiliac joint (SIJ). The concept that this force anteriorly rotates the innominate is now questioned since when the PM is modeled as a pulley over the pelvic brim in the erect posture, the force exerted caused a posterior rotation of the innominate.

The primary roles of the PM are as a lumbar stabilizer by maintaining the lumbar curve and producing axial compression, and a hip stabilizer by creating a vertical shortening that compresses the femoral head into the acetabulum. The function of the PM as a hip flexor is questioned since it is a unipennate muscle with a shortened fiber length, instead of being a fusiform muscle. Measuring the function of the PM at different degrees of hip flexion from 0 degrees up to 45 degrees and past 60 degrees the main function of the PM is hip and lumbar stability. After 60 degrees, its only function is lumbar stability. Only at 45 degrees to 60 degrees is the PM a hip flexor along with being a hip and lumbar stabilizer. Therefore, testing the PM as a hip flexor should only be done when the hip is flexed between 45 degrees and 60 degrees. It may be that the iliacus is more active than the PM during hip flexion. The combined function of the rectus femoris, tensor fascia latae and sartorius may be more efficient hip flexors than the PM and iliacus.

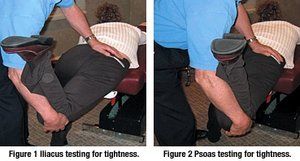

I have used the Mattes2 method of testing for shortness of the iliacus and PM, and consistently find that the iliacus usually is shorter than the PM. Have the patient lie across the table at an angle with the non-exercising leg forward about 18 inches. The tested thigh is extended straight backwards with the hip at the edge of the table and the knee flexed 90 degrees. Holding the pelvis down brings the hip into extension by lifting at the knee. The hip should extend past or up to 90 degrees with a resilient end-feel. The sagittal stretch position tests the psoas for shortening. If you adduct the thigh 15 degrees medially and perform the same test, you will be testing the iliacus. From these positions you can utilize post-facilitation stretch, post-isometric relaxation or active isolated stretching to increase range of motion (See Figures 1 and 2 above).

References

- Vleeming A, Mooney V, Stoeckart R. Movement, Stability & Lumbopelvic Pain: Integration of Research and Therapy, 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone (Elsevier), 2007:95-102.

- Mattes A. Active Isolated Stretching. Available at www.stretchingusa.com.